Review by Frank Plowright

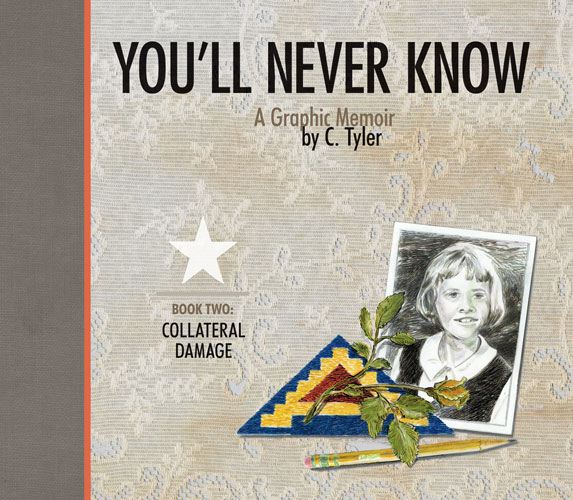

You’ll Never Know began with Carol Tyler deciding to create a scrapbook of her father’s World War II memories, something she continues here in the same entertaining fashion of combining hand-written anecdote with cartoon illustration. It was only decades later, in 2001, that Chuck Tyler had been forthcoming about these experiences.

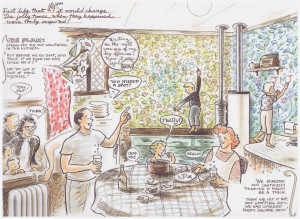

They’re beautifully presented, and what surprises is that Tyler’s style, which looks very simple, is equally suited to supplying comic moments such as his drunkenly driving a tram into an ammo truck and the combat action seen.

Tyler began working on this project during a period of great personal trauma. That also seeped into A Good and Decent Man, and the Collateral Damage of the subtitle here equally applies to how that’s passed on. This is the case with her teenage daughter Julia, who begins to head off the rails, but also of the young Carol, who suffered due to her father treating any admission of sickness as a nuisance.

Despite the subtitle of the previous volume, the more that’s revealed about Chuck Tyler, the less he lives up to it, yet such are the conflicting feelings of family emotion that Carol also continually stresses his better side. Uprooting at age 75 to personally build a new house in the wilds of New York State is ambitious and admirable, yet also shockingly inconsiderate to his wife.

For various reasons the 1990s weren’t banner years for any of the Tylers highlighted here, with serious personal illness affecting her parents. Just before, though, another traumatic family secret is dragged into the light, and Chuck’s method of dealing with it at the time is brutal and appalling. We’re left to wonder how much is genetic inheritance, as his mother is depicted as an indurate and spiteful individual. His finer qualities only manifest in caring for his wife, although even then they’re spliced with moments of callousness.

Tyler’s art is even more impressive than in the first book, once again discovering new ways to tell what’s required. One conversation concerns an accident, requiring the need to depict three people simultaneously supplying their recollections. This is delivered as differently coloured ribbons overlapping and twisting, leading to illustrations of the respective speakers. Sequences set in the more distant past receive distinguishing colour schemes, and panel borders, and when Tyler brings her painterly instincts to bear on the rural scenes there’s real bucolic beauty. The opposite is depicted as she clears the noxious substances from her father’s storeroom.

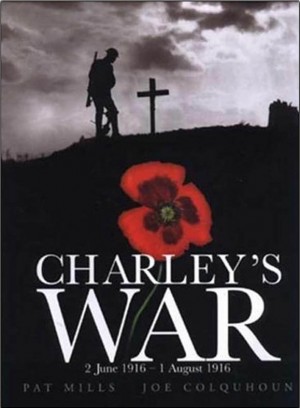

Much of the material here is deep, personal and traumatic, belying the essential cheerful, matter of fact cartooning, but it’s every bit as compulsive as the first volume, and extraordinarily empathic in manner that similar material isn’t. Compare the emotional distance of Maus, for instance, which also investigates the collateral damage of wartime trauma.

You’ll Never Know concludes with Soldier’s Heart, which, confusingly, is the title applied to the 2015 book collecting all three segments.