Review by Graham Johnstone

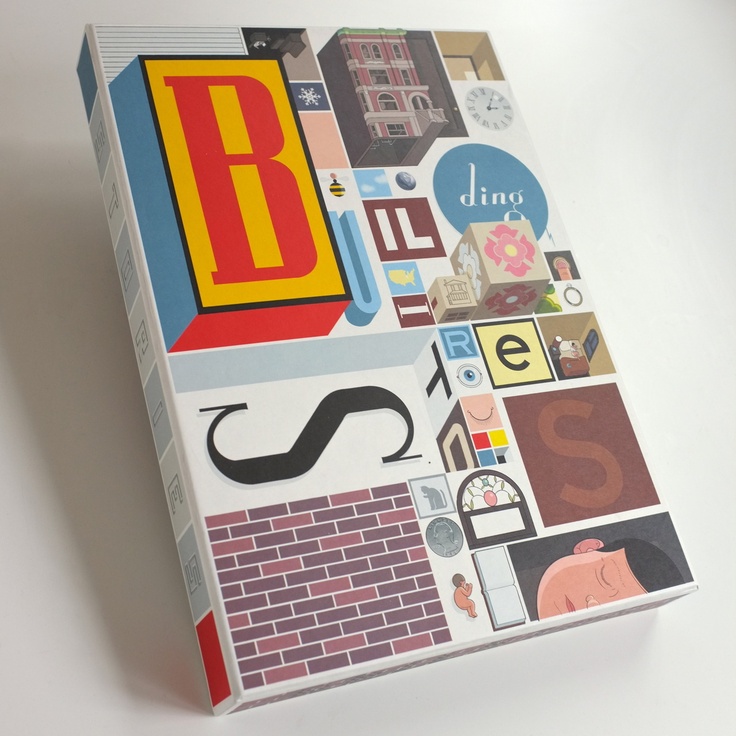

Chris Ware’s Building Stories is a large box containing fourteen items in a range of formats, which can be read in any order, building the stories of the title. They all feature a Chicago ‘brownstone’ and it’s sometime residents: the elderly landlady, a struggling couple, a young single woman with a prosthetic leg, and… a family of bees.

The hardback ‘September 23rd 2000’ has an introduction from the building itself, before following residents over 24 hours, with each hour allocated a page. It’s very low key: there’s some disturbed sleep, arguments, a plumbing fault, a lost cat and a promising encounter with an old friend. Yet by the end of it we know and care about four un-named people, their pasts, their present concerns, and their aspirations for the future.

An item on heavy board concertinas to four ‘pages’ the size of the box. Each page is an exterior shot of the building and environs, overlaid with ‘islands’ of wordless panels, connected by arrows to the people and stories within.

A pamphlet about the couple flashes back to each one’s thoughts when they first met, and contrasts that with their disappointing, deadlocked present.

One about the landlady (pictured) recalls Marcel Proust’s pioneering novel of “involuntary memory”. Scenes outside the window trigger memories from different periods, and with it reminders of the life she missed caring for her mother. Ware conveys this through repeated views with elements changed: period styles, weather and different seasons. There’s also an elegant visual symmetry: an exterior shot is spilt across the two pages, and in the middle panel of each she’s looking through the distinctive window, but in different eras.

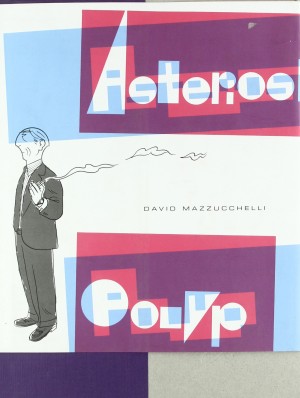

The rest of the material focusses on the (originally) young and single woman before and after her time in the brownstone. The plain-covered hardback (expanded from Acme Novelty Library 18) details her earlier life. Some pages are silent and others perhaps over-burdened with text. She ruminates on bad decisions, and worries about her prospects. She can’t avoid her troubling inner voice and neither can we! Still, for the typically bleak Ware, and given the story’s later focus on death, the overall tone is relatively upbeat.

There is an excellent broadsheet page about her father’s cancer. The text is a continuous monologue in thought bubbles, yet the images are different key moments over the duration.

The Branford the Bee pamphlet and broadsheet are not really meant for children, and can be read as her partner’s perspective. He struggles with identity and desire, eventually leaving the hive and raising a family with a disabled girl bee.

Those familiar with Ware’s art will know broadly what to expect – diagrammatic line drawings with flat but subtle colours, and page designs of sometimes staggering intricacy. There are pages with 40-odd panels. Often parts of rows are subdivided into two or three rows of smaller panels. In these and his two-page spreads with multiple ‘islands’ of panels it can be hard to know the expected reading order. Sometimes he uses arrows, which many traditionalists would consider an admission of failure. At times it feels claustrophobic. One can be both in awe of these pages, and daunted by them. Ware, though, assertively makes a feature of all this.

Such minor quibbles don’t undermine its brilliance, notably by brilliantly solving various new visual challenges. In particular, there are some beautiful drawings of people in darkness, illuminated only by their mobile devices.

Even at the full $50/£30 cover price this is value for money. It’s packed with beautiful objects, and assuming you can read the sometimes tiny and cursive lettering, you should find it affecting and brilliantly realised.