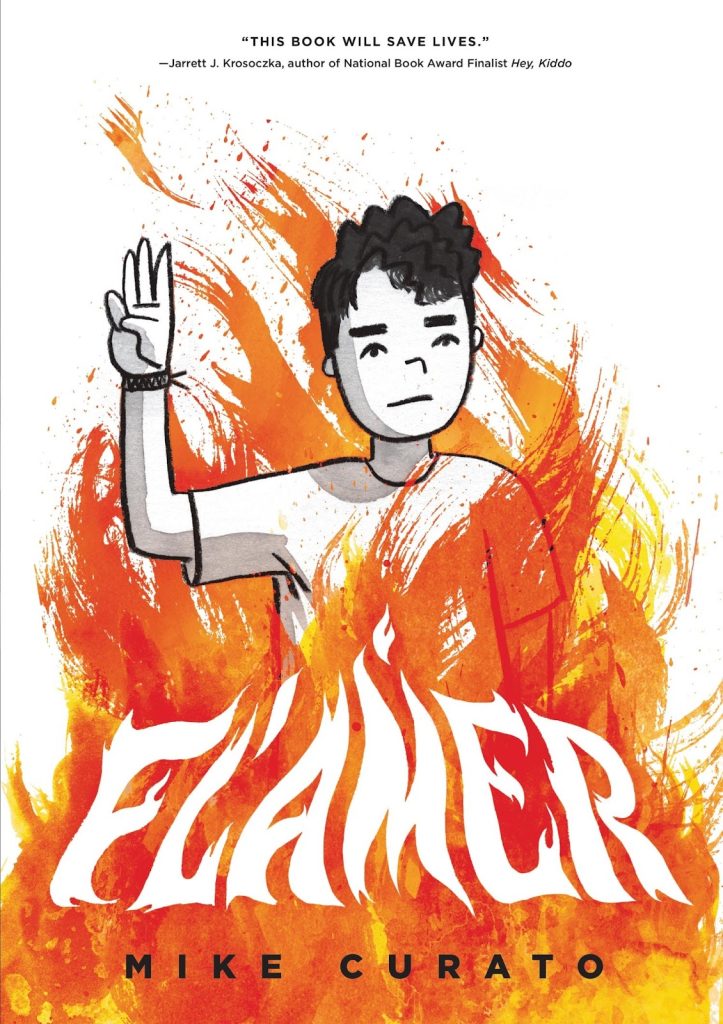

Review by Frank Plowright

Aiden Navarro is fourteen, just about to leave the middle school having hated every minute, and the more he delves into his life and circumstances the more there is to be pitied or appalled at. He’s part Asian, slightly overweight, and would prefer to wear what he likes rather than what fashion dictates, which leads to ridicule. That also comes at scout camp in the form of other kids assuming he’s gay and making offensive ‘jokes’. Still, even that’s better than being at home where life is constantly attempting to assess his father’s moods, looking for the danger signs of eruption that could lead to violence and watching his mother constantly upset.

What Aiden has going for him is that he’s smart and he learns quickly. However, he has the same unvoiceable questions most teenagers have about life in general, amplified by a Catholic background and the accompanying indoctrination reinforcing anything that deviates from a prescribed path is wrong. Flamer? That’s because he fixates on the X-Men’s Jean Grey and the flame that manifests around her when powered-up as Phoenix, wishing it was as easy for him to deal with life’s torments so decisively.

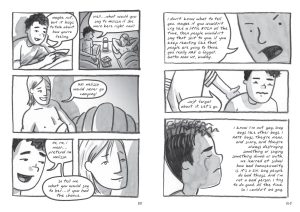

Mike Curato uses what seems a combination of charcoal and watercolour wash, or digital effect, in rough-edged panels creating simple drawings complementing Aiden’s first person confessions. They have the right emotional charge, and enable us to realise what Aiden’s thinking even if he’s denying that in the captions. The writing is as smart as the art, Curato highlighting what seems injustice to Aiden, things no-one should have to put up with in an ideal world, while reinforcing that our world isn’t ideal. It’s noted that most of what raises the blood occurs in the comparatively safe environment of summer camp, and Aiden will shortly be attending high school where there isn’t as much supervision, nor as many safeguards.

This isn’t just a litany of indignity and worse. We come to understand Aiden and there are tranquil moments, and these serve to deflect what’s coming, which is powerful and tragic. Like many people in reality, Aiden feels like there’s no-one he can talk to, and Curato’s characterisation of those who’re meant to understand when confronted with something different is of bigots. An ending conflating the Catholic Holy Spirit with Phoenix is overplayed, yet to take the opposite path of indicating there’s no hope would be shocking, but ultimately no warning. Plus after the story Curato reveals how much was fed in from his own teenage experiences in the 1990s.

Aiden’s journey of self-discovery only really starts over a week at summer camp, and surely echoes the lack of understanding many others experience. As such it’s a beacon of hope, and ought to have a place in every school library, where it will do the most good.