Review by Frank Plowright

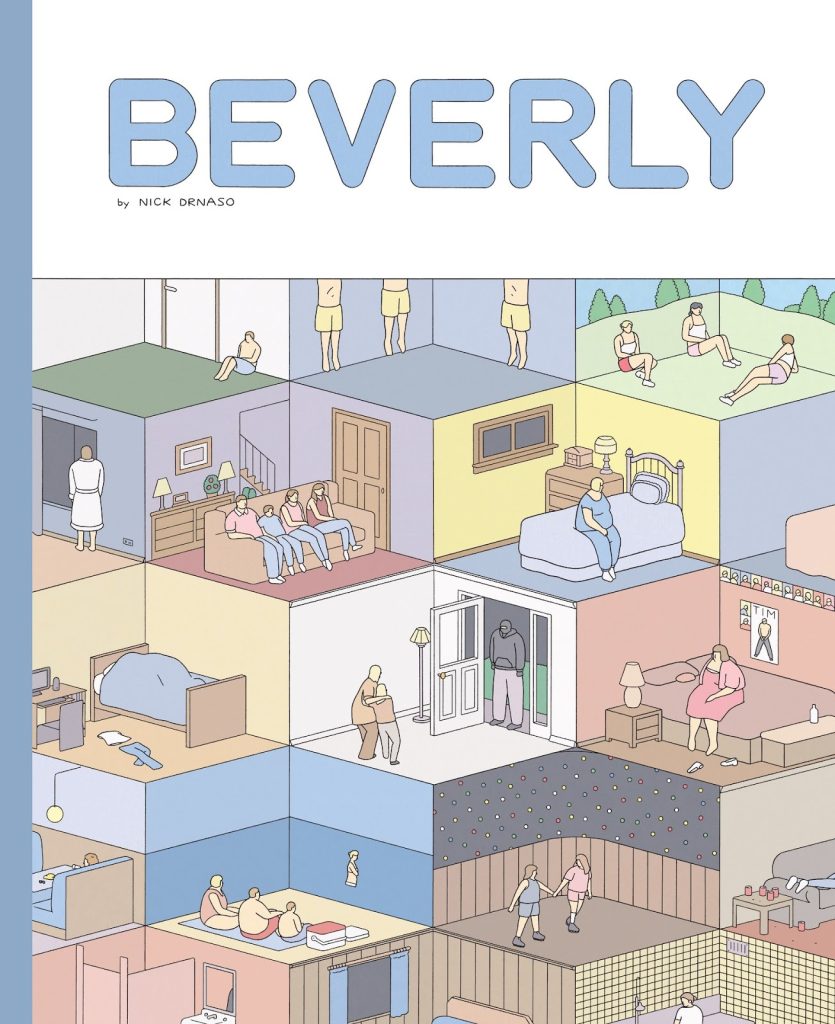

Nick Drnaso’s Sabrina is an award winning contemplation of isolation and trust that garnered widespread attention. It’s only natural, then, that people might look back to Beverly, Drnaso’s earlier collection of connected short stories.

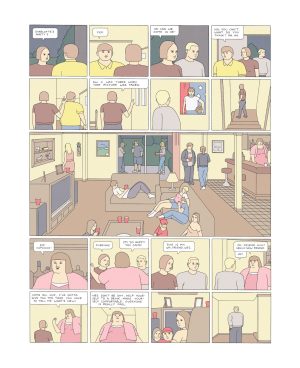

There are considerable similarities, what with the understated approach and the precise art in small boxed panels, and there’s a similar sense of isolation within society, but while praiseworthy and exceptionally well drawn, Beverly doesn’t quite come to grips with making the mundane compelling. It deals with the homogenisation of society via ordinary people lacking any great ambition to broaden their horizons. The inhabitants of a small town serve as exemplars for constriction as Drnaso shows them going about their daily business, on vacation, reconnecting with old friends, and taking part in a community clean-up.

Some stories say what’s needed pithily and precisely, while others linger to no good purpose. A mother is delighted to have been selected to preview and comment on a new TV show, and invites her teenage daughter to participate. It’s a study of quiet desperation, but to establish a punchline Drnaso runs through an entire sitcom deliberately devoid of the slightest inspiration or much humour. The point is made, but at length and not very entertainingly, and that applies to other sections where the observation is sharply naturalistic but doesn’t connect emotionally. Chris Ware supplies an enthusiastic back cover quote, and the similarities between his style and Drnaso are apparent, although Beverly is more linear than Ware’s explorations of despair.

However, as a first graphic novel Beverly is incredibly assured and articulate, has a view to transmit and provides it with some ambition, not least the subtle shift forward in time for every new story. The strongest example is toward the end when the horror of a young girl abducted from a pizza parlour awakens assorted views in the community, all founded on hearsay. Drnaso supplies the comments and relates the responses before the truth is laid out. This is once again slightly clumsy and too long, but ‘Virgin Mary’ is a standout.

A small revelation there informs the skin-crawlingly creepy final story revisiting a character seen earlier. That the two best inclusions end the book points the way forward to Sabrina’s success, but Beverly has its own delights to offer, just not as many.