Review by Ian Keogh

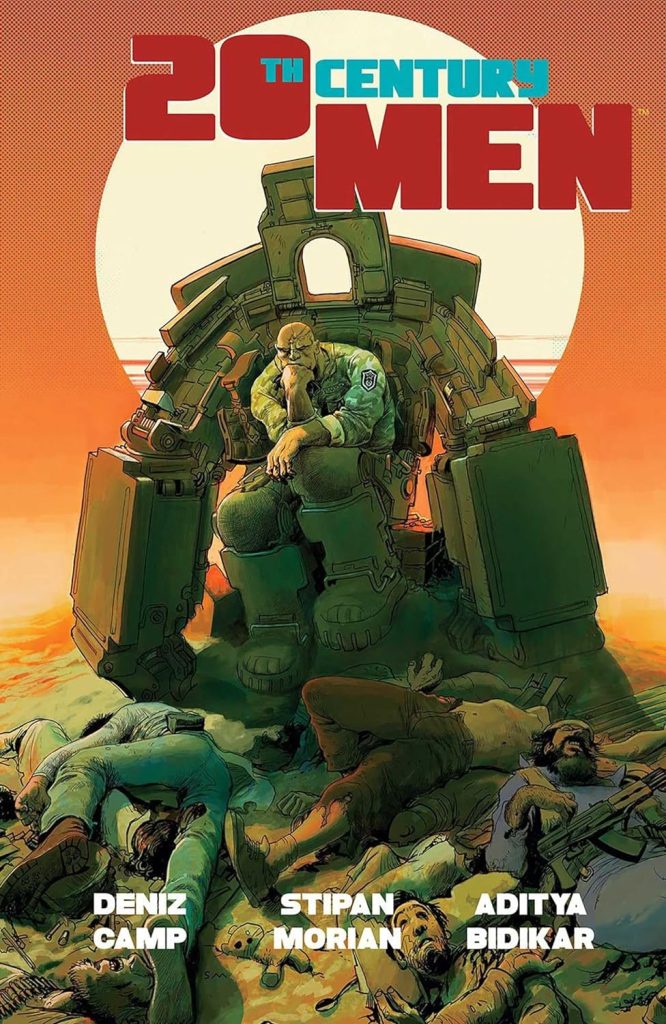

20th Century Men isn’t a story that gives away its secrets immediately, but rather by stealth and requiring observation. An extended opening chapter is broadly set over four locations, first Vietnam in 1969, then Moscow 21 years earlier, with the bulk of the time spent in 1980s Afghanistan before we meet the US President in 1987. There are enough touchstones connecting to our reality, but the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, for instance, is rendered very different for the presence of a man within a massive armoured suit. It’s bulky and unconventional, resembling Iron Man’s earliest armour, yet in a world where other super powers are largely absent, it’s an immensely powerful presence.

So, eventually is 20th Century Men, growing from intriguing to a planet on the verge of World War III. That’s due to other factors Deniz Camp throws into the mix, American capitalism alongside Soviet invasion and the horrors initiated by people who believe they’re beyond reproach or punishment. While others are seen, the primary focus is on the activities of the Soviet Union as represented by both Platanov, the Iron Star, and Krylov, a Pravda journalist not taken seriously by the troops he’s been sent to write about. They’re both in Afghanistan, and both have their certainties challenged, Krylov’s nightmare immersion in reality occupying most of a chapter.

Camp keeps the button to alert and the tensions high, with artist Stipian Morian very good at providing different environments and varying his style according to the needs of the plot. When American specialist troops are seen during a battle, Morian supplies frightening fanatics in football helmets, all painted bright red, yet when calm is called for he can deliver deep human emotion. The mixture of linework and painting is complementary, about the only aspect of 20th Century Men that isn’t clashing. It’s fantastic art depicting appalling events.

Monsters invading paradise over ideological differences is what this ultimately amounts to. We’ve been presented with several scenarios at a deliberately slow pace, largely to establish Platanov’s inherent contradictions as a man to whom possibilities are endless, yet locked to a flawed system. He’s Captain America in reverse. For all the downbeat mythologising, though, Camp is an optimist at heart, and the feeling is the point at which the writer’s screen comes nearest to dropping altogether is when he presents an alternative society. The weakest point is the inevitable ending of a superhero battle, albeit one distilled to single representatives of competing ideologies, coupled with a caricatured analysis of capitalist priorities.

To complain about a predictable ending when considering what’s come before, though, is to diminish that achievement. Camp has taken a familiar trope and supplied an intelligent and stylish twist offering thoughts on the world as it is and a prayer for something better.