Review by Frank Plowright

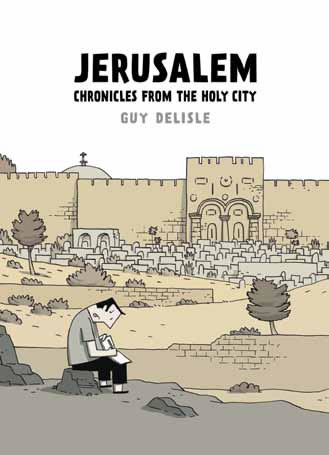

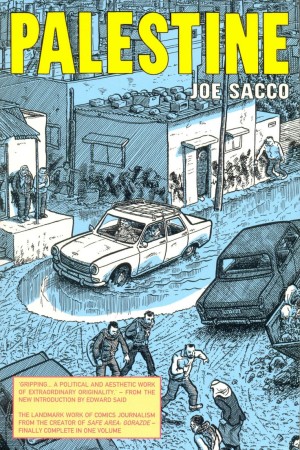

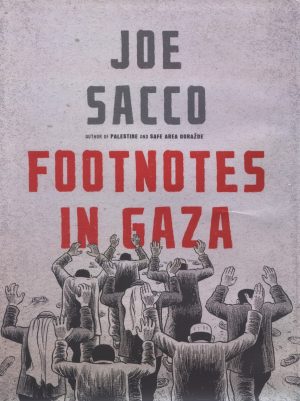

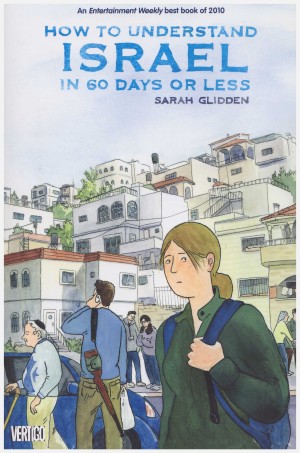

Since Joe Sacco first published Palestine, there’s been a quiet accumulation of graphic novels dealing with the situation of Israelis and Palestinians, ranging from the overtly political to the travelogue. They have almost all, though, been good recommendable work, and Guy Delisle raises the quality of that list.

Jerusalem is another stopover on Delisle’s tour of the world’s more troubled areas, staying for a year from July 2007 with his wife Nadège, an administrator for NGO Médecins Sans Frontières. Only one child accompanied them in Burma; now there are two, and his experiences are very much framed by the necessity of caring for them. This begins with the effect of the local mosque’s late night call to prayer on a sleeping baby.

Delisle is very much the laid back raconteur. He conveys his points, but this via astonishment as he wanders the city, and genial engagement with the people he meets as a sort of French-Canadian Bill Bryson. There’s no hectoring here. Delisle will be looking at a map during his wanderings around the city and note the 70 checkpoints for Palestinians in a relatively small area, or have to explain the concept of war to his infant son. It builds into a bigger picture, and, as is always the case with Delisle’s autobiographical reportage, it’s very vivid. This despite his explicitly distancing himself from the label of reporter.

As a stranger in town, Delisle has a resigned weariness to the perpetual small indignities of life and a quizzical silence when someone attempts to explain the inexplicable. Delisle twice takes a tour of Hebron, once with a member of an activist organisation of former Israeli soldiers, then as run by settlers in the area. There’s an immense difference in tone. At the lower end of the scale the inexplicable is the discrepancy of whether or not Jerusalem is Israel’s capital (mebbes aye, mebbes no).

In previous books Delisle has commented more, but in North Korea and Burma ordinary members of the public face severe consequences for a mild departure from official dogma when talking to a foreigner. In Jerusalem he’s able to relate the first hand experiences of others. He becomes quite obsessed with the massive security wall constructed to prevent free movement for Palestinians, and several people tell of the impact the wall has on their lives, none positive. There’s an appropriate comment from an Israeli psychologist who lived in Derry, with their wall separating catholic and protestant communities. “At least we don’t have this in Israel” is what she once thought.

Delisle notes the prevalence of guns openly carried in the city, how most residents are desensitised to this, and his lack of religion ensures no accusation of bias when commenting on the religions of others. While other cartoonists have portrayed life in Jerusalem as lacking hope for the better, Delisle takes a different approach, highlighting the gradual thawing of relations between the Palestinian police and an Israeli security detail seconded for a papal visit.

As previously, Delisle’s simple cartooning is very adaptable in supplying detail, character and experience. An innovation is the sparing and effective use of colour.

It’s interesting that this is the book of Delisle’s to win the coveted Angoulême Festival prize. It’s larger than his previous works, but they were equally insightful, equally well sketched, and those were from areas inaccessible to most people so might be considered to have a greater narrative value. Perhaps is that there are incidents in which he’s inadvertently involved. Whatever the reason, as previously, Delisle entertains and painlessly informs about a place most find difficult to understand.