Review by Frank Plowright

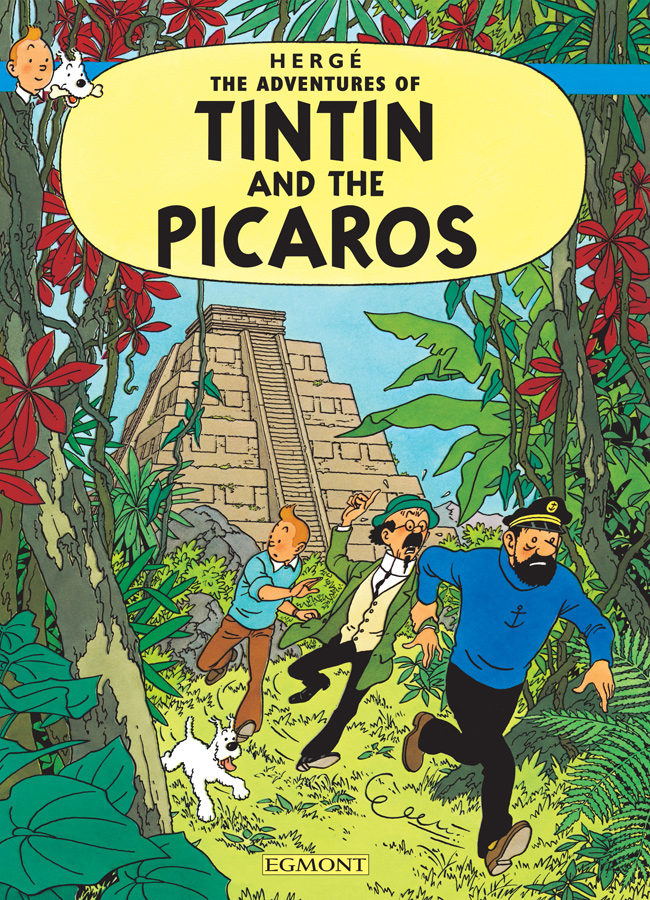

Eight years elapsed between Flight 917 and Tintin and the Picaros, which would be the final completed Tintin adventure. Hergé was increasingly stressed at even the thought of having to work on another story, and occupied himself by travelling extensively. Meanwhile, the germ of an idea he’d had about South American revolutions and dictatorships continued to percolate.

On hearing the news that opera singer Bianca Castafiore has been arrested in San Thedoros, Captain Haddock is initially amused, but his hilarity is transformed to anger when he, Tintin and Professor Calculus are linked to fermenting revolution. San Thedoros was last seen over fifty years previously in The Broken Ear, but its then president General Alcazar manifested in exile in two further books. Now back in his homeland, he’s gathered a band of rebels, the Picaros, named after the local tribe with whom they live, and plots to depose his enemy General Tapioca, previously mentioned, but never seen. Lured to San Theodoros, the main cast members again link up with Alcazar.

Despite the political scenario against which events play out, Hergé never lets concepts from the real world overwhelm the tightly plotted adventure narrative, and this is considerably better than some critics would consider. Divesting Tintin of his by then way out-moded plus fours and replacing them with brown jeans dates the book in a manner that leaving him be wouldn’t have, but this is trivial. Much is also made of minor changes to cast members, and the accumulation of them supplying the story with a valedictory air. Despite his distaste for the pressure to continue Tintin, Hergé always denied it to be his farewell, and despite the crowded cast everyone has a part to play. There’s even a memorable new character, Alcazar’s ghastly wife.

There remain, though, two major mis-steps. One is the strange switch of allegiance from a minor character that remained unexplained, and smacks of plot convenience. The other is that Tintin aids the revolution not from strong moral convictions as per previous motivation, but because Alcazar is a mate. Despite extracting a promise no blood will be shed, which pays off in comical elements at the death, there’s no attempt to ascertain who will be better for the country. Hergé supplies his own view via two pointed panels of the poverty-stricken shanty towns and via media manipulation in the story, but it’s not via an ambivalent Tintin.

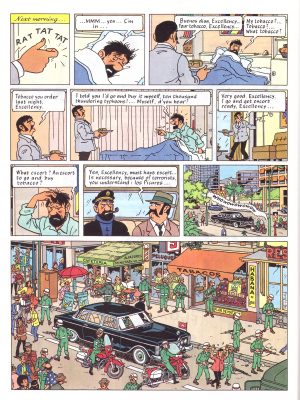

Still, this is a comedy adventure, and there are plenty of well-played comic sequences from Haddock’s sudden aversion to whisky, through to Bianca Castafiore’s demanding and ear-piercing cameos to Thompson and Thomson considering their final words.

The art is spectacular. By the mid-1970s only Bob de Moor remained to assist, but there’s no lack of detail, delicacy or any storytelling deficiency. Cameo-spotters can enjoy scanning the carnival sequences, while the lush jungle, and the modern city provide fantastic scenery.

Were the creator of Tintin and the Picaros anyone but Hergé it would be acclaimed as an astonishing piece of work. The only manner in which it appears substandard is in comparison with other Tintin material, and the top volumes number among the best graphic novels ever. Some folk protest too much.