Review by Frank Plowright

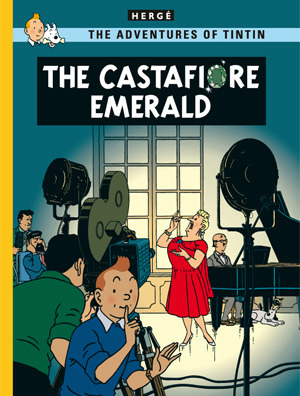

The Castafiore Emerald is Hergé’s masterpiece, which is remarkable as it completely upends the foundations of Tintin’s success. There’s the broadest cast of familiar faces, but they all descend on Marlinspike, Captain Haddock’s well-appointed country estate, where the entire narrative occurs. This, and recurring elements with consequences such as the broken step on the staircase, deliver an impression of a structure along the lines of the classic Georgian farce, rather than the expected exotic adventurous travelogue.

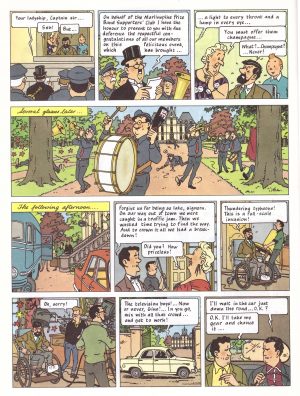

Haddock is sent into panic by the telegram announcing the imminent arrival of opera diva Bianca Castafiore, here progressing from cameo to her only starring role in Tintin. Unable to bear the thought of her piercing soprano echoing around the building he immediately plans to absent himself, but in his haste forgets the broken step and the resulting accident ensures his confinement at home. Castafiore and her entourage duly arrive, and much is made of the jewels accompanying her. Thereafter unfortunate incident is layered atop unfortunate incident, not the least of which is a newspaper story announcing La Castafiore’s engagement to Captain Haddock. It enrages him, but to the publicity hungry Castafiore all press is good press, despite her pretended abhorrence for some magazines.

As tensions rise at Marlinspike, small valuable items go missing, culminating in an emerald given to Castafiore by the Maharajah of Gopal. There’s no shortage of possible suspects, Hergé having spent a fortune at the red herring shop. The spotlight first falls on the gypsies Haddock has allowed to camp on his land after being outraged at the local authorities restricting them to a rubbish tip. They’re very sympathetically treated throughout, in particular Tintin berating Thompson and Thomson for jumping to unwarranted conclusions on hearing of their presence. For some critics this is Hergé underlining his aversion to racism and prejudice, accusations that lingered from his World War II experiences. Toying with the readers, Hergé dispenses with the possible culprits one by one, deliberately supplying the most mundane reasons for possibly furtive behaviour or mysterious occurrences.

In places the art is as experimental as the structure, particularly a sequence in which Professor Calculus demonstrates his prototype colour television. Hergé supplies a series of vivid distortions in pop-art style. Elsewhere it’s the stunning ligne clair art expected. Particular gems include sequences with Haddock on the phone, complicated not only by crossed lines, but also by his anger at the talking parrot Castafiore’s given him, and the inebriated band on page thirty. In a brilliant comic aside, they number among their members the builder never able to visit to repair the broken step.

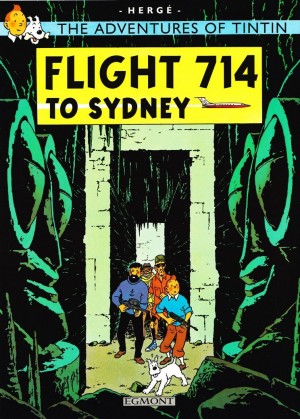

Hergé‘s own comment on the book was that he aimed to tell a story lacking any exotic elements and preserve the suspense until the end. He also commented that setting the book in Haddock’s home surely represented his own subconscious desire for a break. After averaging a book every 21 months since beginning Tintin he’d only complete a further two books in the following thirteen years. Five years would elapse before the next, Flight 714.