Review by Frank Plowright

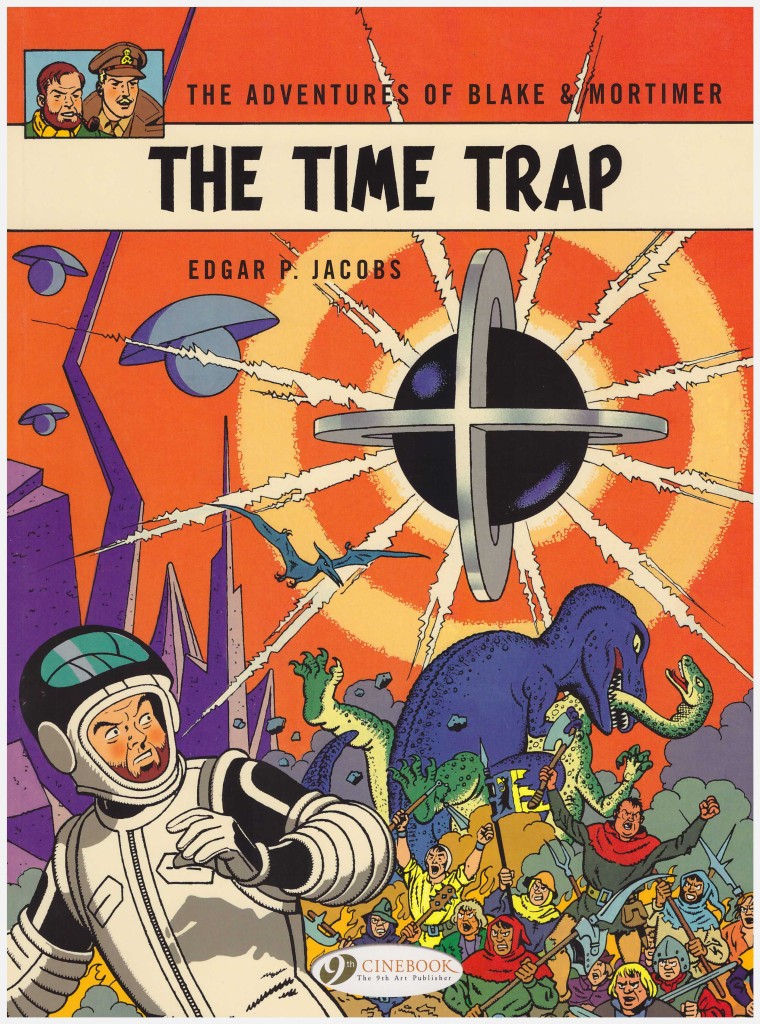

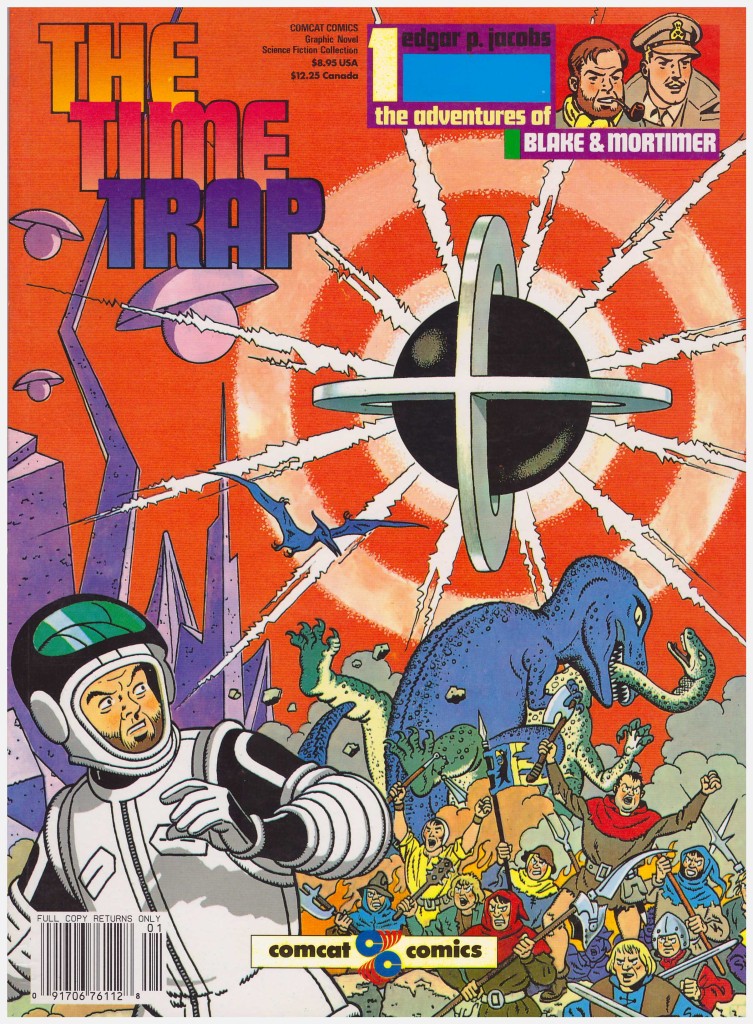

When Catalan first attempted to introduce Blake and Mortimer to the English language market in the 1980s via their Comcat imprint, The Time Trap was the volume they began with. Yet Cinebook relegated it to 20th in their series, their final publication of an original Edgar P. Jacobs volume occurring after they’d already produced several by his successors. There’s a reason for that.

This was the ninth of the eleven books Jacobs completed, issued in 1962, after a comparatively long wait since 1959’s S.O.S. Meteors. The gaps between albums would increase. The Affair of the Necklace didn’t appear until 1967.

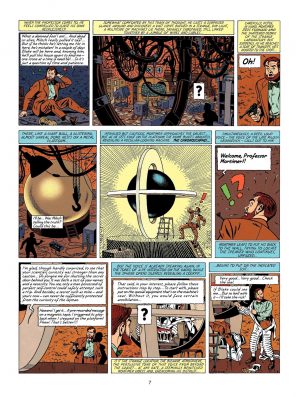

The Time Trap is an atypical Blake and Mortimer book, being primarily a solo outing for Professor Philip Mortimer, as Blake appears only in the opening and closing pages, and it’s far more episodic than linear. Milosh, the villainous scientist seen in S.O.S. Meteors, has died, and his bequest is to Mortimer as an honourable foe able to appreciate the wonder of his final invention. This is a time machine, but the fine tuning control breaks as soon as Mortimer tries the device.

He’s catapulted back into pre-history, then forward to a revolution in medieval France before jumping to the future, for his longest adventure, posited by Jacobs at the end of the 21st century.

It’s complete in a single volume, but otherwise The Time Trap shares the pros and cons of Jacobs’ other work on the series. He illustrates in a very attractive shadow-free clear line style, but can’t be bothered to break his pages down to avoid excessive dialogue. These days Chris Claremont’s work is considered over-written, yet he rarely exceeded thirty words per panel. Page 38 opens with a 48 word panel, and that’s followed by another four easily tripling that total as Mortimer learns about how the condition of the late 21st century occurred. Jacobs never shies from great blocks of text, not a fault in itself, but he equally never realises that most could be considerably emptier yet still convey what’s required.

As the dialogue indicates, Jacobs was very plot motivated, and characterisation is sparingly applied, but this book hasn’t dated as well as his other work. Time has surpassed him, and what was an exciting plot in 1962 must now be compared with numerous far more imaginative and better realised versions of time travel and the future.

It’s worth noting that the Cinebook edition is a better production every respect than its Comcat predecessor. It’s printed in traditional European album size, coloured more subtly, and features a far better translation from Jerome Saincantin. This extends to maps and graffiti in the story being translated rather than left in the original French.