Review by Frank Plowright

The magic and mystery of childhood is captured in impeccable manner by Aaron Renier whose story blurs around the edges to convey that feeling of not quite understanding everything. It playfully subverts reality by positioning a sculpture class, and by extension art, at the centre of a social storm that divides a town. Almost all inhabitants fear a sea monster believed to live in the old closed pond, and a proposed exhibition there renews old anxieties.

Renier perfectly captures the manner in which self-assertion and uncertainty manifest in teens. Turnip, the young elephant introduced in the opening pages is ostensibly shy and withdrawn, yet confident enough to want to work with marble rather than clay. Ana is utterly confident, unconcerned about rattling skeletons as she investigates the past, yet Stucky, who on the surface seems the same, is someone who reaches out, wanting friends.

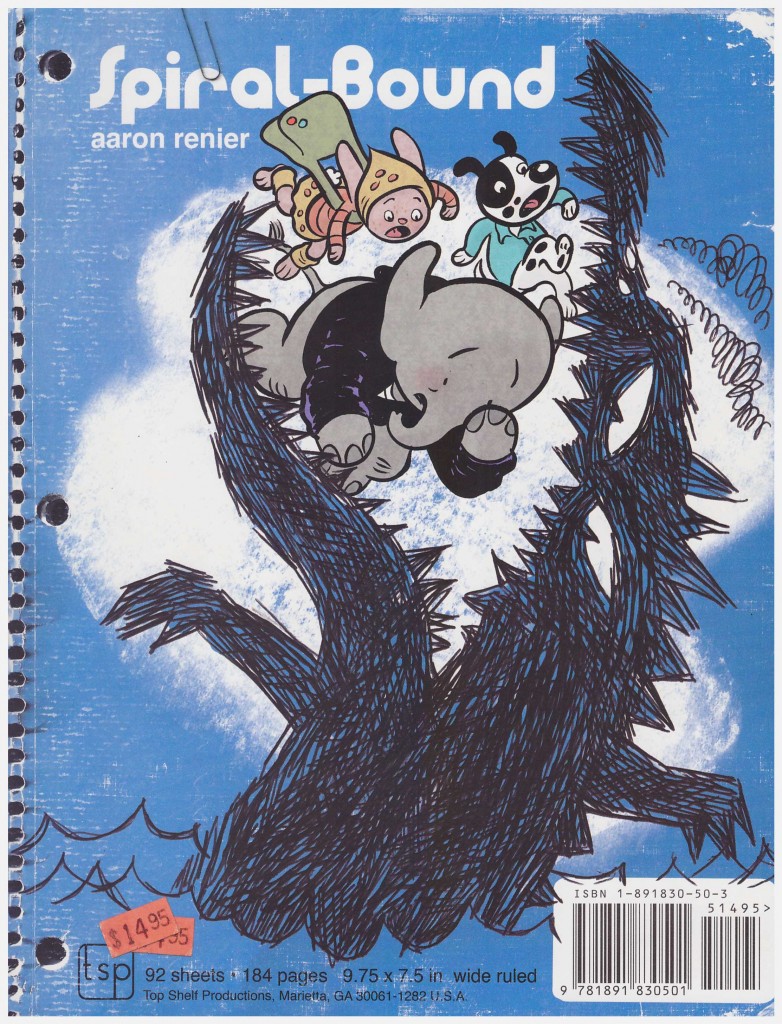

The cartooning is fantastic and almost insanely detailed when it comes to locations. Having decided his cast are animals, Renier grasps the concept by the throat and throttles it with no concern for scale or logic. A small bird flies about with a heavy camera around its neck. Turnip’s father stomps around a bookshop scaled for those a quarter his size, and the sculpture teacher’s a spectacled whale, in a giant water-filled sphere resting on a hydraulic digger attachment. Ana’s family live in a tree, while everyone else has houses. At one point Ana and Emma disguise themselves as Turnip with a home-made costume and everyone is fooled, even Turnip himself as Renier recycles the Duck Soup mirror gag.

There’s so much care and thought delivered in Spiral-Bound. An example: early in the book a snake talks about taking the sculpture class. “How’s he going to manage that?” immediately comes to mind, yet a few pages later Renier shows us exactly how. For Renier it’s not enough to introduce a secret underground railway, he’s worked out how it connects with all areas of the town he’s conceived, and provides a map at the end of the book. In keeping with Ana’s journalistic ambitions, the entire book is designed as if drawn on a spiral-bound notebook complete with rounded corners, although the lines on pages don’t extend into artwork.

This graphic novel ought to charm any adult with children, and those children, but the adults will have to leave their attachment to real world logic behind and embrace the whimsy Renier’s provided.

Earning a living from illustrating children’s books means Renier is hardly the world’s most prolific creator of graphic novels. His next, The Unsinkable Walker Bean, followed five years later.