Review by Karl Verhoven

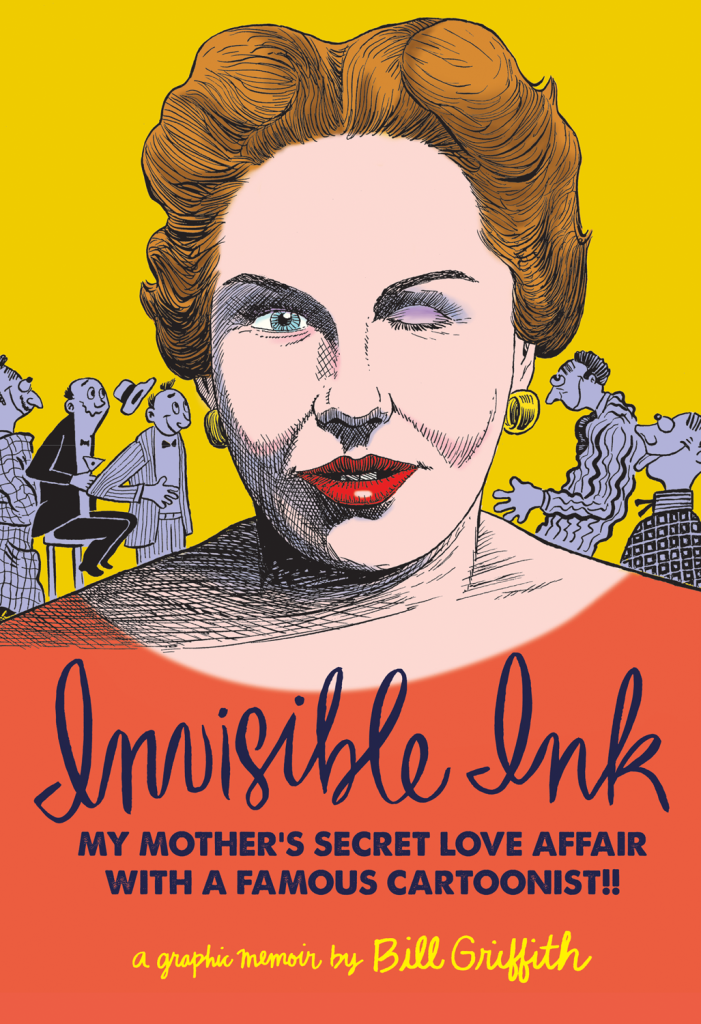

It’s somewhat surprising to realise that despite a consistently innovative career extending back to the 1960s, wonderfully curated in Bill Griffith: Lost and Found, this is Griffith’s first true graphic novel. Of course, producing his Zippy the Pinhead syndicated strip on a daily basis won’t leave much time for sustained additional work.

The subtitle of My Mother’s Love Affair with a Famous Cartoonist!!! reveals the focus of this story, but there’s a leisurely lead in to the heart of the matter. Few will be aware, for instance, that Griffith’s great grandfather was renowned photographer William Henry Jackson, whose career spanned over seventy years. Jackson was still working in his nineties, and was a centenarian at his death in 1942.

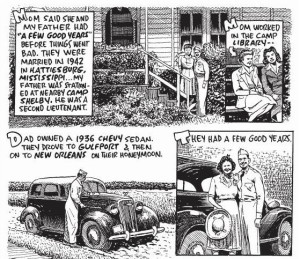

Griffith uses the artifice of a train journey to drop details of his family history and background. His father was an unfulfilled man for whom anger was a default setting, and with whom Griffith had a troubled relationship, while his mother was a vivacious beauty whose parents were equally sparing with their love. Other snippets suggest a family with more skeletons than a graveyard, and a callous attitude to their own, never mind others. After chatting with his uncle Al and viewing some old photographs Griffith muses about what he expects from some family memorabilia: “My emotional attachment to these people is tenuous at best. I mean I’m free of their influence.”, before noting “Then why won’t they shut up?”

His mother’s affair was no secret at that point, as she’d told him in unusual circumstances in 1972, and given what Griffith reveals about his father’s manner and domestic expectations, in this day and age it would seem only natural that his mother might seek solace and respite elsewhere. This, though, began in the buttoned-up society of 1957.

Like all the best biographies Invisible Ink draws us in by revealing as much about the author as the subject. Griffith’s initial latter-day interest in Lawrence Lariar is motivated more by professional curiosity about a fellow cartoonist, with his mother’s relationship secondary, and he reveals a man whose pen dipped everywhere. “Cartoonists are, in the main, simple souls moved to simple expression of simple ideas”, wrote Lariar for a book introduction in which a paragraph later he recommends the study of Daumier.

Much is unconsciously revealed of Griffith’s cartooning, which draws heavily on the syndicated strip artists of the 1930s. That strong hatched style enables an effortless switch into pen and ink portraiture, landscapes and particularly technology, beautifully rendered in what might be seen as an outmoded fashion. It’s better considered as timeless. Griffith also re-draws several of Lariar’s bawdy cartoons.

There’s a meta-fictional aspect to Invisible Ink as Griffith adapts scenes from his mother’s unpublished novel revealing her life. He’s uncomfortable about some revelations, while also speculating what difference a responsible and encouraging father figure might have made to his own life.

This is a meandering journey, and not all questions are resoved. It’s a loving portrait of Barbara Griffith, and an admiring one of Lariar, whose restless creativity in numerous fields is now completely forgotten. He bequeathed his papers to Syracuse University in 1981, and in all the years since only Griffith has asked to view them. In some respects he’s the real life counterpart to Seth’s fictional Kalo from It’s a Good Life if you Don’t Weaken.

Anyone not keen on the surreal whimsy that characterises Zippy the Pinhead, should have no qualms about sampling the straightforward content of Invisible Ink. It’s a masterful and compulsive study, at times intensely personal, but always eminently readable.