Review by Frank Plowright

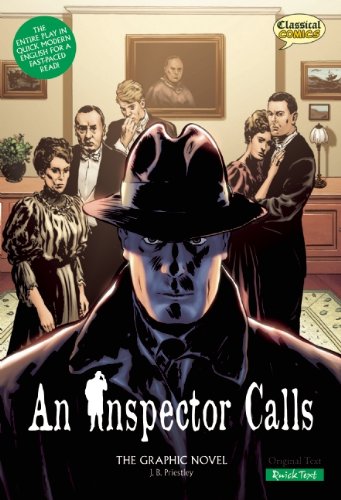

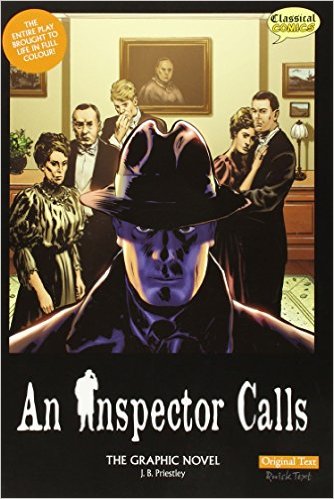

Sixty years after its first performance An Inspector Calls remains a powerful piece of social commentary, but it’s an odd choice for a place among the first dozen literary works to be adapted by Classic Comics. It’s very static piece, set in a single room, and dependent on awful lot of talking heads in comic form. On the stage at least there’s some variety provided by the movement and gestures of the cast.

J. B. Priestley’s play is set in Edwardian Britain, but is a searing indictment of social conditions prevailing until the end of World War II, during which it was written. It opens as the Birling family enjoy a dinner to celebrate the engagement Gerald Croft of to their daughter Sheila. Arthur Birling is a local factory owner who served, as he likes to remind people, as mayor for two years and is expecting a knighthood. Pompous and overbearing, he has a supportive wife, who’s equally austere in her own manner, despite being head of a local charity committee. Son Eric disagrees with much of his family’s methods and politics, but hasn’t the courage to say so, instead drowning his convictions with alcohol, while Sheila has some common sense, but also failings. Croft is the son of another local businessman, and Birling sees the forthcoming marriage as uniting dynasties.

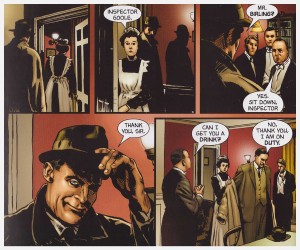

The dinner is interrupted when Police Inspector Goole arrives to question those present. He announces the suicide of twenty four year old Eva Smith, and the opening revelation is that she once worked in Birling’s factory. Goole’s abrasive and persistent manner grates on Birling, but the longer he remains, the more the dinner party reveals to him.

Will Volley’s artwork is severely limited by the constraints of the text, but he manages to break-up the constant talking heads in a single room by providing flashback visuals of some events related. There’s a hint of Gene Colan to his brushwork, and he distinguishes the cast well.

All Classical Comics adaptations are published in two forms, one featuring the original text and the other presenting it in simplified English. Priestley’s original dialogue was deliberately direct and plain, so Jason Cobley’s changes made for the “Quick Text” contract a few words here and there and remove specific historical references. The wholesale bowdlerisation that occurs in their adaptations of Shakespeare isn’t required, and it could be asked whether any alternative was needed.