Review by Frank Plowright

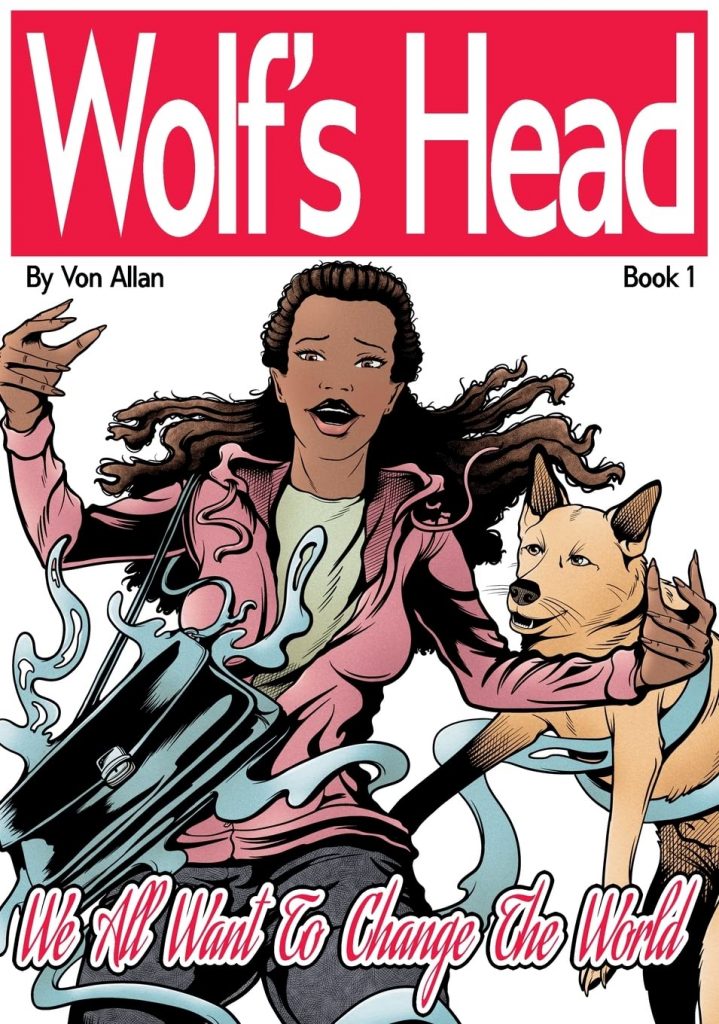

Von Allan sure suckers the reader’s instincts with Wolf’s Head. We see Lauren Greene quit her Detroit police job on principle, and over an engaging opening chapter we learn about her concerns, how she’s inclined to do the right thing, and about her mother Patty, who has a heart condition and with whom she has a strong relationship. We meet Lauren’s friends and her mother’s dog Sankó, are told about the factory fire that’s impacted on Mrs. Greene’s breathing, and are taken on a tense tour of the neighbourhood. It turns out that Patty’s boss isn’t the considerate and understanding individual he makes himself out to be, and Allan ends the introductory chapter with a bombshell.

By that point we’ve realised Lauren’s no paragon of perfection, but someone we can like and admire as much as the local bar owner does when she’s venting. Along the way Allan makes valid points about society’s expectations, which when analysed are stacked decks. Employers want people with degrees, yet acquiring one needs a lot of money. It’s a leisurely form of storytelling benchmarked by dates and times, which at first seem just a quirk, but it’s actually a well conceived marker, the passing of time related to events and Lauren’s frustrations. When events become more tense, it’s even more valuable. While Allan ensures we’re caught up in Lauren’s day to day life, it’s not the entire story, which contains an element of the fantastic. It’s not intrusive, in fact barely seen for the first third of We All Want to Change the World, but the eventual impact shapes events.

It also shapes the art. As most of Wolf’s Head is based on day to day realism it requires artistic discipline, and Allan’s methods convince, only slightly failing when it comes to under-populating Detroit’s streets. Lauren is written as someone who wears her heart on her sleeve, and that’s well illustrated, the variety of expressions displaying what she feels at any time. The surprise that sparks the story is something else altogether, and it’s very much an artistic release, giving Allan a chance to mix the abstract with the routine, which isn’t as simple as might be assumed. Michael Allred seems to manage it effortlessly, but too many other artists are unable to mix their forms of reality convincingly.

Lauren is well characterised from the start, but the people she’s surrounded by, good, bad and indifferent, are also easily understood, their motivations clear, which enables the plot to roll out smoothly. By the end the We All Want to Change the World title has taken on a different meaning, and over an enjoyable 160 or so pages Allan has supplied a drama to lose yourself in, and set up a lot of potential going forward. In an age of effects wizardry being cheap, TV production companies could do far worse than look in his direction.

A generous amount of process material completes the collection, with Allan revealed as a likeable person who worries too much about his colouring.