Review by Ian Keogh

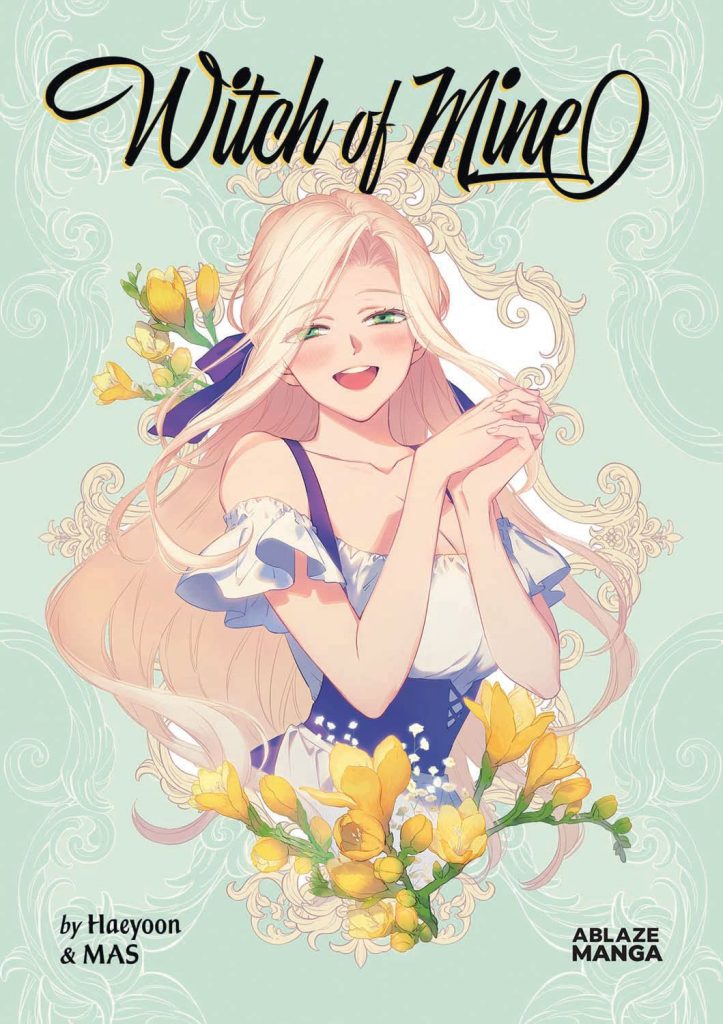

Despite some gorgeous drawing by MAS, Witch of Mine hasn’t been the most accessible title. Witches have been revealed as separate from humanity, but drawn to human lives, especially the capacity of people to experience love. Cordelia appeared in what was primarily Phillippa’s story in Autumn Song, and takes the leading role in Flower of Evil.

It’s an extremely disturbing story on several levels. We’ve seen witches indulge in wholesale slaughter already, and MAS is relatively subtle in the depiction. The same applies to the boot being on the other foot when Cordelia is overwhelmed. She’s saved when a young boy doesn’t disclose her weakened presence, but that leads to a deranged obsession on her part. Although she doesn’t look it, she’s ninety, and Haeyoon’s story has her deciding a nine year old boy is an appropriate choice for her affections. If that seems beyond belief, justifying what follows by stating love has no reason is astounding. Is Cordelia using magic to appear a similar age and befriending Michael not just grooming? As shown, what eventually happens does so naturally merely through Cordelia’s presence, but it’s a decidedly provocative way of introducing a relationship.

As before, Haeyoon doesn’t make it easy for readers to follow his story, using a very disassociative style. He switches from one scene to another without warning, too many word balloons still remain unattributed and there are no prompts from the art, so confusion is a continual accompaniment. It’s eventually clear that Cordelia’s presence in the village beginning the first volume was due to her passion, and what seemed bullying and jealousy on Phillippa’s part actually has some justification. Alongside the unsettling content Haeyoon addresses violent abuse of a child, which makes for more uncomfortable reading, and from her outsiders viewpoint Cordelia is mystified by several further aspects of human cruelty and intolerance.

Once again on a page by page level the artwork is stunning. MAS draws attractive figures using a delicate line, but almost nothing else, and the people within large white areas with barely any backgrounds gradually lose their charm.

There’s a feeling that some content is intended as comedy, although there’s not a doubt about a ridiculous birth sequence, but much of it doesn’t translate well, and it’s an awkward combination with the upsetting material. In the end what does transmit is possessive compulsion substituting for love, but somewhere beneath real feelings exist. By the end there’s a poignancy that’s expunged the disturbing moments.

It extends to the back-up story, which shines a different light on someone who’s played a relatively large role, and is also sweet. It makes the overall lack of clarity even more frustrating, because there’s something really good in the mix that really need to be brought out, not buried. Glass Plate is next.