Review by Frank Plowright

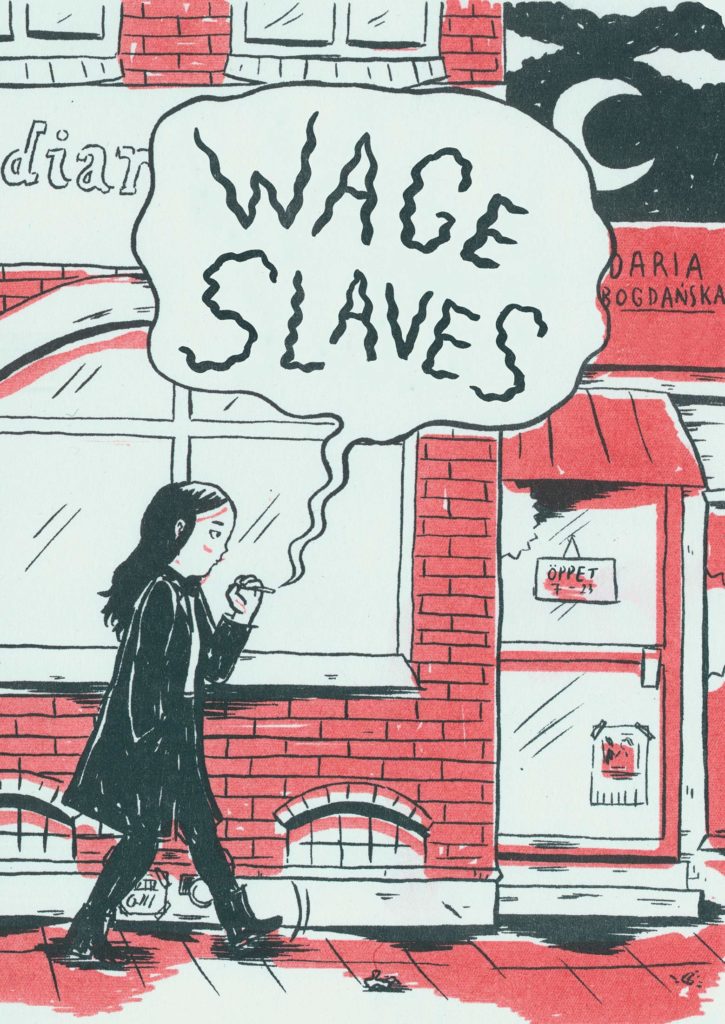

Daria Bodanska travels from Poland to the Swedish city of Malmö to take a cartooning course, but only has enough money to cover her first month’s rent. She’d anticipated picking up a job easily enough, but that wasn’t the reality resulting in this graphic novel. The legitimate job market isn’t accessible, which leaves Daria scrabbling about for employment from people aware she could be exploited. A succession of disappointments follows, but she has to stick with these jobs if the rent is to be paid. She’s fortunate in meeting Mendi soon after her arrival, an upbeat and supportive friend of a friend, and he gradually introduces her to people that open the door to other opportunities. As Daria learns, while she’s hardly joyous, others have it plenty worse.

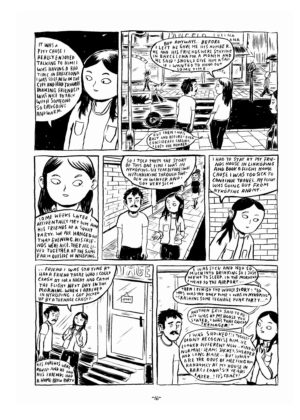

Busy, flat and two-dimensional, the art is good at evoking a place. Daria stays in some complete pits, and each is rendered as scuzzy, the density of the black ink indicating the level of dirt. Factored against this is an extremely limited capacity for emotional reactions. It’s rare that anything is conveyed by means other than different placement of the eyes.

As seen on the sample page, it seems as if no detail is too trivial to be left out, accounting for Wage Slaves accumulating just short of two hundred pages, and pages not filled with such bulky conversations can feature exactly the opposite, Daria wandering alone through the streets of Malmö. On some occasions this is to emphasise the emptiness and limited opportunities of a life with very little money, but on others it’s wasting space. We don’t need to know the exact route from Daria’s flat to the club where she meets Mendi.

Because there’s so much scene setting, the feeling begins to develop that Wage Slaves will be nothing more, but just before halfway the narrative finally kicks in. Daria’s been recommended to contact a Union, and a thread beyond the daily grind then runs as the background to Daria agonising about relationships and repeated restaurant scenes. It’s her life, but in relating it she dilutes the aspects of greater general interest. Occasionally pieces of her background buck this trend, and you’d wish for these to be expanded on, but they’re just in passing, burying the real story.

By the end, in terms of her job Daria’s achieved something worthwhile, and a fair amount of what she has to say applies universally, not just in Sweden, which makes it frustrating that Wage Slaves isn’t the graphic novel to put this over. Multiple meandering scenes occur, but clumsy lectures and information dumps are crammed into a single page. Wage Slaves has its moments, but digging them out is a slog and the key points would have been more effectively made if distilled into considerably fewer pages.