Review by Frank Plowright

In the early 1980s British rock act John Dummer and Helen April used the B sides of their singles to provide utterly ordinary three minute slices of life about making a cup of tea or feeding the cat, complete with all relevant sounds. They were whimsical, true to life and compelling. The Walking Man embodies a far greater ambition, but is the graphic novel equivalent. It’s an incredibly precise title for a middle-aged man’s strolls around Tokyo. Along the way he derives enormous pleasure from small moments, from the interests or activities of the people he meets, and from the conditions, whether they’re sunshine or rain.

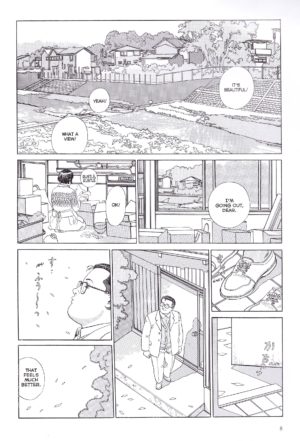

The above synopsis could interpret The Walking Man as an expensive ticket to tedium, which is so far from the truth. It’s an almost unique graphic novel rejecting so many constant narrative imperatives and setting a calming mood as it embodies John Ruskin’s philosophy that everyone can learn from just looking more. Jiro Taniguchi emphasises this with an opening page that’s simultaneously a statement of intent. It’s used as the sample art, and is the simplicity of a man announcing to his wife that he’s going for a walk on a beautiful day after appreciating the view from his window. Taniguchi lingers on what could be considered irrelevant details, yet this is the invitation to walk out with the man into Taniguchi’s vision. For the complete immersion in his experiences he suggests we consider the sounds and smells as the man emerges from his house. From that page Taniguchi takes us over a bridge to see a fish in the river beneath, also closely observed by cats, to a more rural area where a bird watcher passes the time. It’s uneventful, yet serene and absorbing.

In order to ensure the general experience is immersive as possible the sheer amount of detail Taniguchi adds to each panel is astounding. Gloriously rendered scenery is almost taken for granted, but a similar work ethic is applied to architecture, clothing and the skies. A natural assumption would be that there must be a limit to the scenarios to be exploited, which isn’t the case. What’s experienced changes according the weather, the purpose of the walk or the interactions with others. Taniguchi certainly found that 22 stories weren’t enough to satisfy his creative impulses, and later produced a thematic sequel Furari, of a man walking around 17th century Tokyo, or Edo as it was then. It’s also capable of instilling a mood of calm and serenity as we follow the perambulations, and so another way to look at The Walking Man is it being the comic equivalent of ambient music. Not everyone will buy into the essence, but for those who do The Walking Man is a masterpiece.

Three strips at the end mess with the established feeling, perhaps prototypes. They’re heavier on the narrative captions and one is an emotional introspection, drawn in a different, shadowy style. Walks around Tokyo occur, but they’re reflective and of greater purpose than appreciation of the surroundings. While not exactly intrusive, their placing at the end recognises their altered mood.

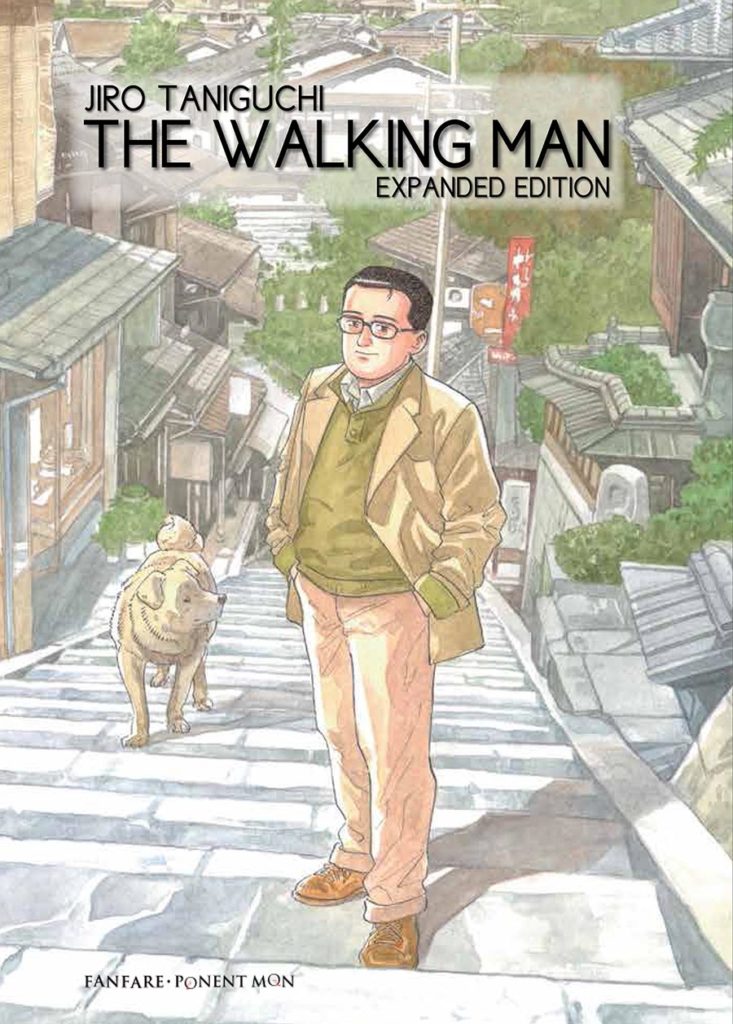

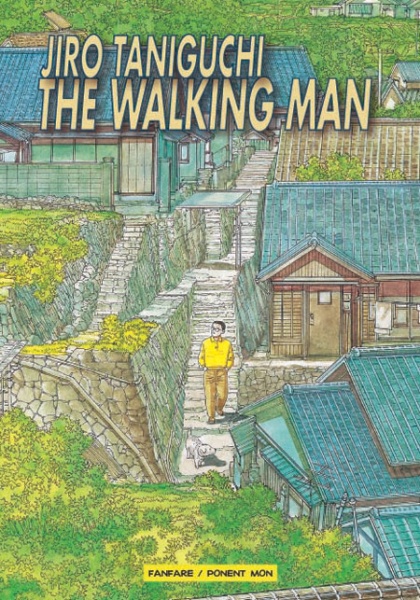

There are two available editions, the standard black and white version, and the 2019 (in English) Expanded Edition, which comes in hardcover, features colour strips and reads in the Japanese manner from back to front. That’s the one to go for.