Review by Frank Plowright

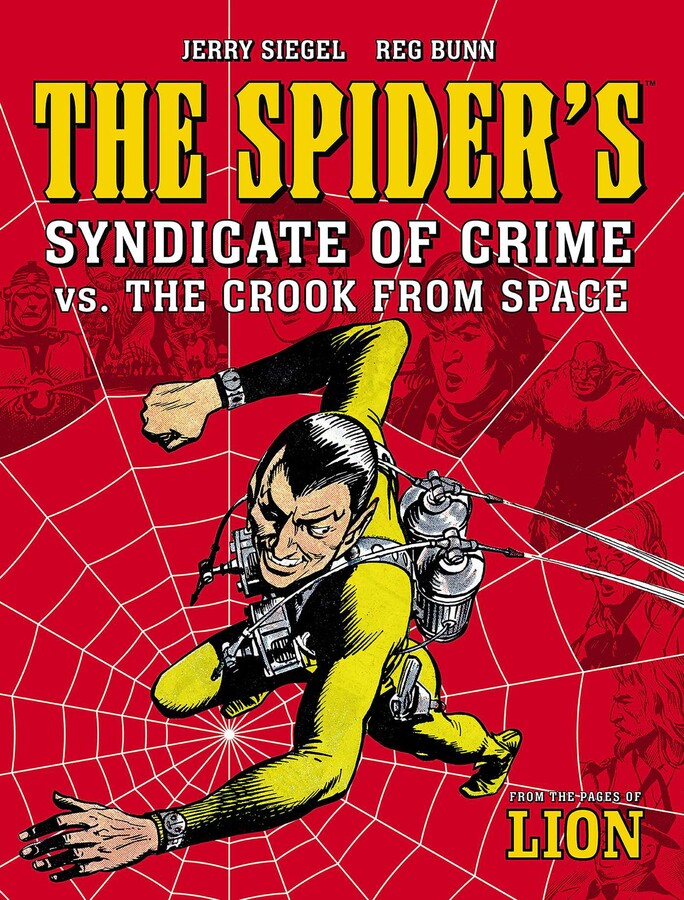

Incredible as it seems, and testament to what a scummy industry comics was, by 1966 Jerry Siegel, co-creator of Superman wasn’t kicking back in his own Hawaiian beachfront mansion, but scrubbing around looking for work wherever he could get it. Part of his portfolio was writing the New York adventures of criminal mastermind the Spider for British comics.

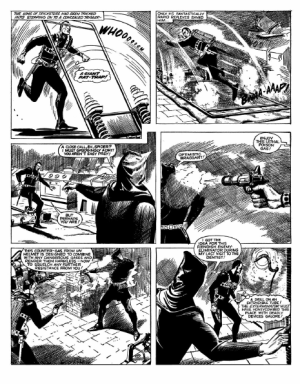

The Spider is from the old school of boastful, monologuing villains, yet forever devising fantastic devices. The first episode alone showcases his personal jetpack, his exotically shaped helicar, instantly drying liquid plastic, steel thread webbing and a gun creating a smokescreen. This was a fantastic array in the 1960s, and still impresses today as drawn with the precision of Reg Bunn.

Siegel adjusts easily to the demands of serialising stories in 24 panels a week, ending each with a cliffhanger, and this collection supplies two tales. In the first the Spider battles against the Exterminator, a hooded villain also aiming to take control of the criminal underworld, and realising he’ll have to dispose of the Spider to make that possible. As explained by the volume title, the second concerns a crook from beyond Earth.

In both cases Siegel keeps the suspense high and the traps ingenious, and the Spider’s methods of escaping them equally so. The dialogue isn’t sparkling, but where it comes to life is with the Spider’s absolute confidence in his own invincibility and contempt for anyone putting that to the test. It’s a minor complaint anyway when held up against Siegel’s imagination. The work he produced for American comics in the 1960s was of a man who didn’t understand the zeitgeist, but he grew up on the pulps, and applies their action principles to the Spider’s adventures.

In Bunn, Siegel is paired with an artist whose work now looks old fashioned, but it’s the only strike against a perfectionist whose work ethic is monumental. The panels are packed with figures, yet never seem crowded, and he adds depth via complex crosshatching and shading. His most remarkable achievement is the Spider himself, forever sinister. Whether action or conversation Bunn delivers what’s needed with impeccable technique.

There’s a sea change for the second story. Siegel ends the first by having the Spider decide being a criminal no longer offers him any challenge. In the course of the adventure he defeated strong foes with ease, and henceforth he’ll use his talents to combat crime. The first to come onto his radar is the Gadgeteer, who proves a challenge, but not as great as the alien who subsequently arrives. Siegel fudges this slightly, opting for thrills above logic, so the alien’s capabilities are attuned to the needs of individual strips, but he certainly puts the Spider through his paces until an extremely abrupt, but superbly drawn ending.

By today’s tastes the Spider’s adventures lack sophistication, but that’s trumped by verve, invention and Bunn’s draughtsmanship, and because the strips are so dense this offers a couple of hours wallowing in nostalgia. More is found in The Crime Genie.