Review by Karl Verhoven

The Spectre is one of DC’s oldest characters, co-created by Superman’s originator Jerry Siegel in 1940, first sent back from the dead as an avenging spirit, and later considered to be the embodiment of God’s wrath. He was all-powerful from the start, but beyond the simplistic original stories this proved problematical. Forgotten during the 1950s, he was unsuccessfully revived in the 1960s, and more controversially in the 1970s before being sidelined again for the 1980s. It seemed no-one knew how to handle such a powerful character with close ties to God. Step forward John Ostrander.

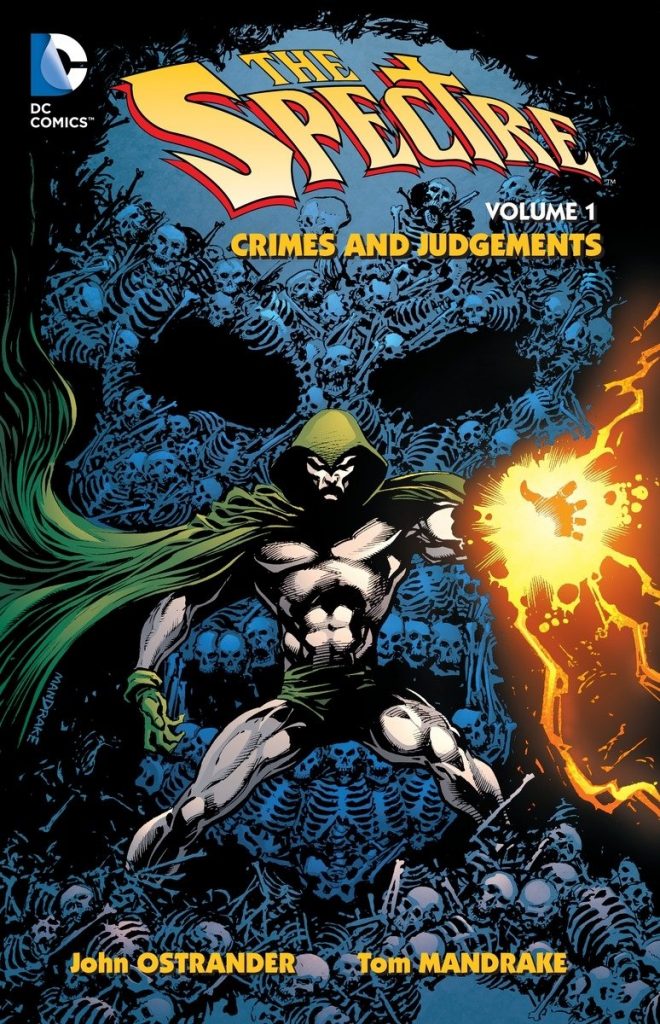

It was because he was all-powerful that rendered the Spectre problematical from the point creators began to think a little more about superheroes. Who can oppose an entity that can do literally anything? As shown, not even the Lord of Hell, although at least he puts up a fight. Ostrander took a step to the side, accepting that as given, and instead created conflicts from ethical concerns and questioning. In the earliest chapters, collected in 1993 as Crimes and Punishments, we meet social worker Amy Bietermann, whose interrogative nature first sets her on a path of tracking the Spectre down, and then to confronting him about what he accepts as his God-given right to execute criminals. After that the Spectre investigates whether he is, in fact, a soul from hell bound in service to heaven, and Amy convinces him that perhaps if he understood humanity a little more he might be able to persuade early rather than murder late. “If despair is one kind of hell, then anger and vengeance are two more. What is justice without mercy, without compassion?”. At heart the Spectre is still as he was created, merged with hard-boiled cop Jim Corrigan who died in 1940 with the attitudes of his era, so it gives him pause for thought.

In posing questions, Ostrander successfully integrates all previous versions of the Spectre into the single consistent being, from the all-powerful 1940s version to the gruesomely vindictive 1970s version. Not everything is gold. Ostrander can become bogged down in the assorted moral arguments, a policeman substituting “Balzac” for swear words is a mistake, and a serial killer plot is strung along for too long.

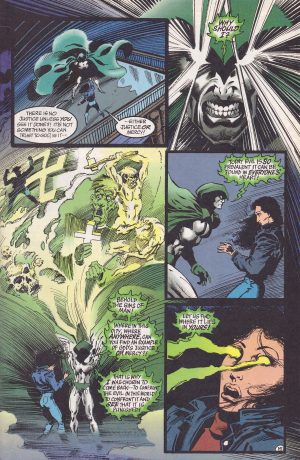

The Spectre has phenomenal visual possibilities, but for around half the book Tom Mandrake doesn’t make the most of that, squashing the character into panels, and even on occasions when the Spectre lets loose not presenting the spectacle. It’s so fundamental that it draws attention away from the good of Mandrake’s art, which is almost everything else. When he does cut loose, as per the sample art, the effect is phenomenal, true old testament horror, and when he hits his stride Mandrake’s depiction of Hell taps into something primal and unpleasant. This isn’t a few rocks, a few fires and a demon with a pitchfork, but really disturbing stuff. It wouldn’t be out of place in Hellblazer.

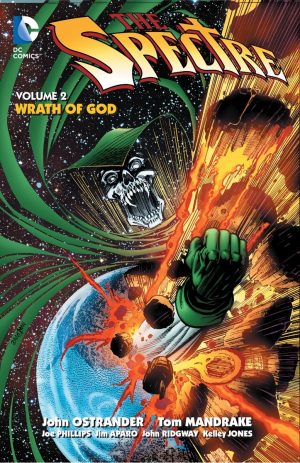

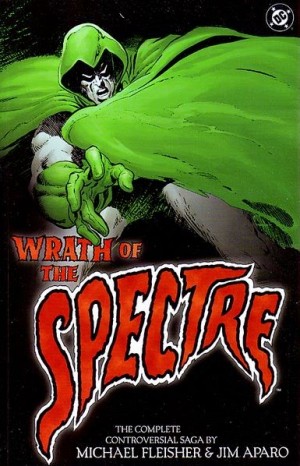

Crimes and Judgements is unusually cerebral for a 1990s mainstream presentation, and it’s somewhat dry in the earliest chapters, yet Ostrander isn’t afraid to head for the down and dirty, stalk and slash horror movie territory as a counterpoint. The final three episodes are a mini masterpiece of that genre, the Spectre occupied elsewhere, the tension cranked up unbearably and Mandrake pulling out all his storytelling tricks to achieve that. It’s very satisfying, and also satisfactorily fits in a plot that until then had seem unconvincing. A second volume titled Wrath of God followed.