Review by Frank Plowright

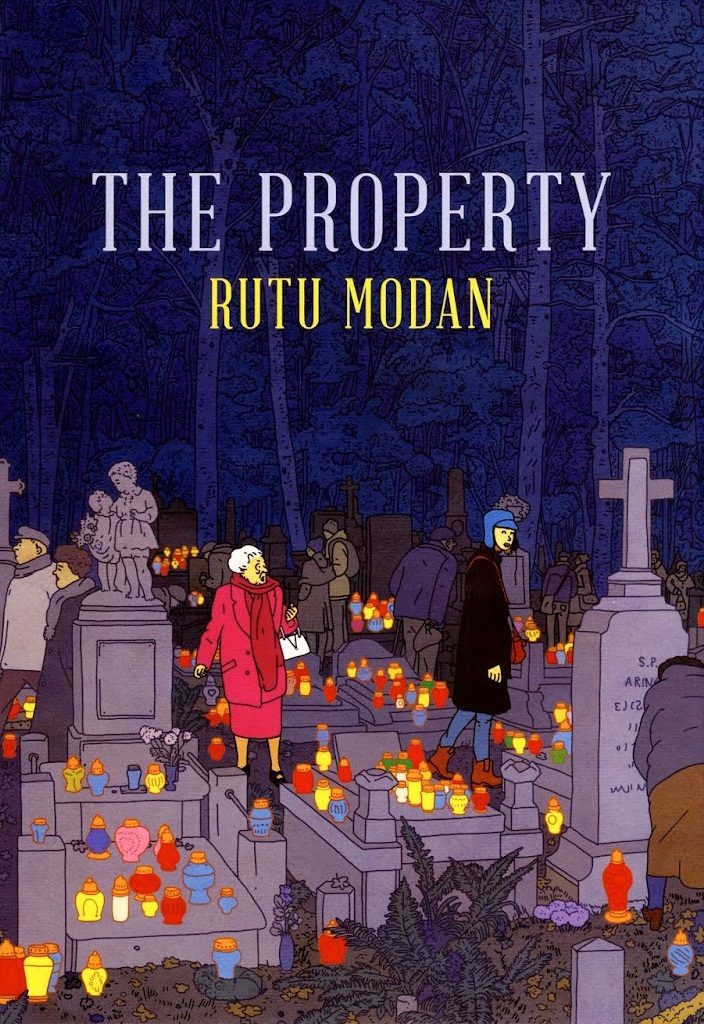

Rutu Modan instantly engages audience sympathies in The Property by featuring the curse of the 21st century traveller being unable to take a bottle of water through airport security. It’s a comic scene, yet also establishes just what a stubborn woman Regina is. She’s accompanied by her adult granddaughter Mica on a trip to Warsaw, ostensibly to negotiate the return of family property lost during the Nazi invasion of World War II, but Regina has other ideas, and immediately changes her mind. To Mica this is random strange behaviour, but Regina has spotted a name in the Warsaw telephone directory.

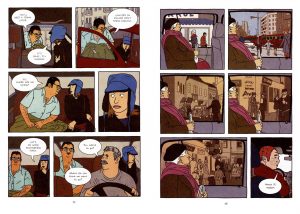

Regina is only the first of a wonderful parade of characters Modan introduces, each of them fully realised, but The Property isn’t really her story, as Mica gradually assumes the focus. She’s used to her grandmother’s eccentricities, and confident enough to travel alone around Warsaw without speaking Polish, although as seen from the sample illustration that’s not how things work out. The other person is a family cousin who just happened to be on the same flight, and has a particularly over-protective and interfering nature. We learn quickly his presence on the flight was no coincidence, and that he has ulterior motives for much of what he does, although this is a family story, not a crime drama where motivation is kept secret. Plenty has been undisclosed over the years, and in the course of a few days much unravels.

The Property is a marvellous read, the type of rich, well observed human drama unfolding at its own pace that is still comparatively scarce. The works of Posy Simmonds are a close relative, Modan substituting comments on Jewish culture for those Simmonds makes about middle class pretension, but both produce dramas requiring close observation of other people. A suspension of disbelief is required as some elements fall too neatly into place, the random first person Mica meets in Warsaw being an absolute solid charmer for one. That he’s also a comic artist at first comes across as a little too self-aware, but it resonates during a later dramatic scene. Modan also explores Jewish connection with the Holocaust in a decidedly individual way. Had anyone not Jewish written the same incident, accusations of trivialising might have flown, but this isn’t insensitivity, more a scathing satirical statement on how the Holocaust has become materialised.

Modan’s art has developed with every successive project, and there’s now a delicacy to her ink line and a greater visual sensibility. An impressive early scene conveys the emotional weight of a meeting Regina plans, and when it occurs there’s a marvellous detachment before true feelings break through. Much of this is achieved without words. Mutan also notes the lack of inhibition among the elderly, especially their propensity of not caring for political correctness, and Mica’s reactions to a couple of these occasions are wonderfully conveyed.

It’s difficult to imagine any adult reader able to enjoy a drama not connecting with The Property in some way. It was almost universally praised on release, and time hasn’t changed that perception.