Review by Frank Plowright

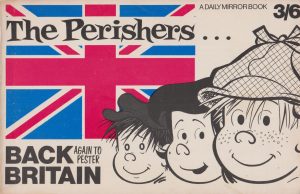

While the UK has a long history of newspaper strips, there’s not the breadth of quality and innovation that can be found in North America. Perhaps it’s why there’s a far more casual attitude to archiving strips, most of which are only available in the annual landscape format paperbacks issued at the time. There are, however, some strips every bit as good as American work, and The Perishers can stake a viable case for being the best ever British gag strip.

It originated as locally produced for the Manchester area, but the first strips collected are those circulated nationally when Maurice Dodd came aboard as writer, joining in-place artist Dennis Collins. Peanuts was an obvious influence on a gag strip about children where adults remain unseen, and there are similarities between the aggressive force of nature that is Maisie and Lucy from Peanuts, but by national UK syndication The Perishers had forged its own path.

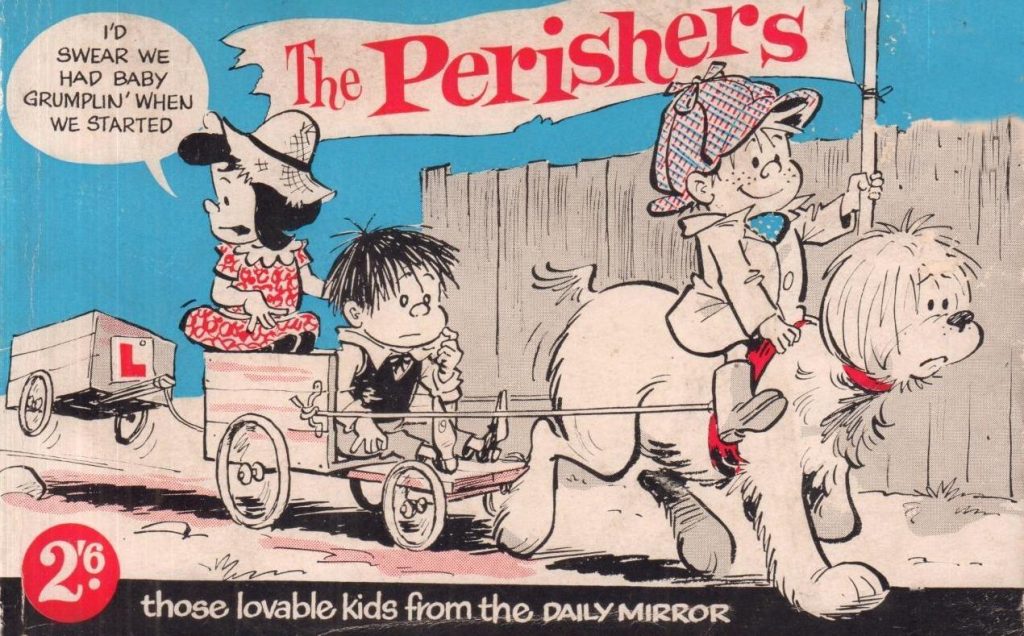

The leading characters are the homeless Wellington and his old English sheepdog Boot, each a vehicle for a different form of Dodd’s philosophical musings and social observation. Wellington tends to comment on the randomness of existence and the marvels of nature, while Boot’s observations largely concern the illogicalities of human behaviour. Right from the start Dodd works wonders considering questions such as whether the weather targets individuals. Despite being dim and befuddled, Marlon is Maisie’s choice of boyfriend, and the main cast is rounded out by Baby Grumpling, unwilling to speak, but certainly smarter than Marlon.

They’re brought to life by sharp cartooning from Collins, who worked out all stylistic deficiencies when the strip was regional. Boot’s form would slightly alter over the first few years, and Baby Grumpling would lose his wooly hat, but Wellington, Marlon and Maisie are pretty well as they would be for years to come. Dodd hasn’t yet introduced the signature panoramic strip, but his work ethic is already present. It’s a rare strip not featuring full figures, and the detail on the clothing is immaculate. Backgrounds are largely simple, but when something special is needed, Dodd delights.

Themes that would see the strip through the next fifty years are already being introduced. There are jibes at Dodd’s then day job in advertising, Maisie’s intimidation and a befuddled Boot. Other recurring jokes like Baby Grumpling’s reign of terror on a tricycle and Wellington’s inevitable losing encounters with the never seen Bully Bloggs would fade.

Rather than reprint the strips chronologically from late 1959, this 1963 collection is arranged to follow themes Dodd introduced, sometimes juggling them within sequences for no apparent reason. A selection of early strips considers Maisie’s accusation of Marlon being bereft of ambition, yet the first strip is followed by the final word, before the remainder see print. The strips are given an identification code and number, so S298 is from late in 1959, while T31 originally saw print in February 1960.

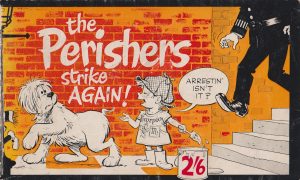

While the refined slapstick accompanied by poetic observation is still funny, there are obviously signs of the times with strips this old, particularly the clothing Dodd draws so well. However, the chances are that The Perishers will still resonate with contemporary readers. A selection of the strips can also be found with Dodd’s amusing commentary in the first Perishers Omnibus, along with some from The Perishers Strike Again.