Review by Ian Keogh

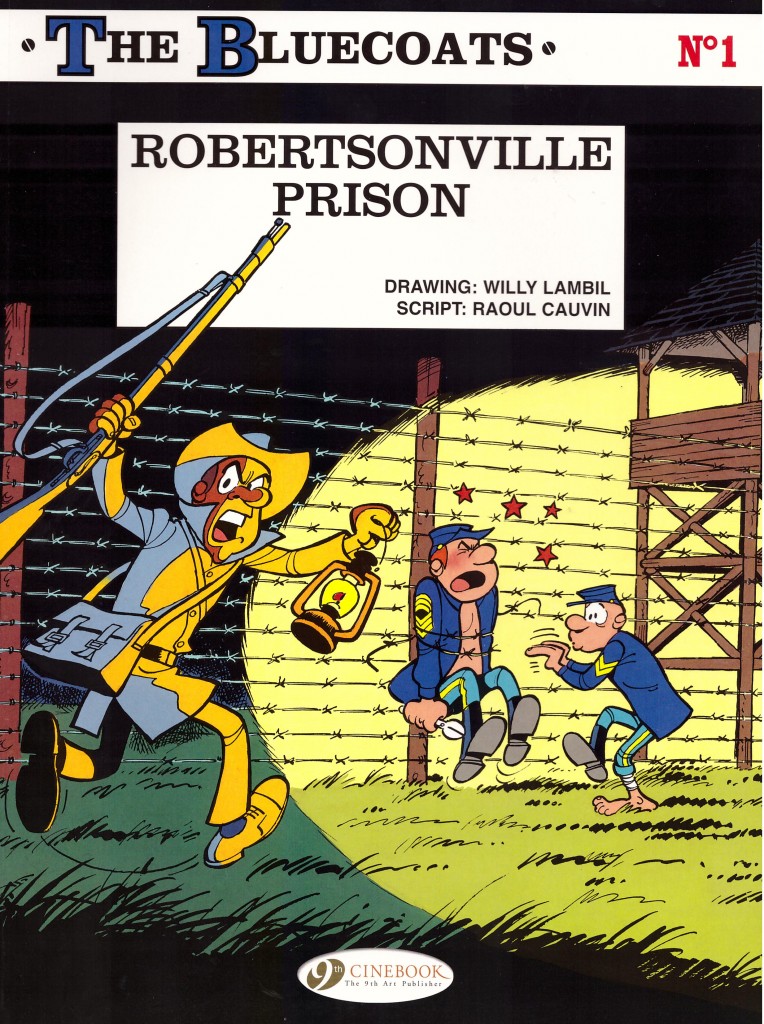

Raoul Cauvin created the Bluecoats as a comedy adventure series featuring two Union conscripts during the American Civil War. In 1972 the original series artist Loius Salvénius died of a heart attack while illustrating what became the fourth book, Outlaws, as yet unavailable in English, which was completed by Willy Lambil. He continued on the series, with Robertsonville Prison the sixth in what’s become an immensely successful concept, accumulating almost sixty graphic novels to date.

Sergeant Chesterfield and Corporal Blutch may have their reservations about serving in the army, but life in a Confederate prison camp is even less to their liking. Cauvin bases his prison on the notorious Andersonville camp of the era, and in protecting a wounded Blutch, Chesterfield makes an enemy on the forced march to the jail. This is the brutal prison guard known as Cockroach, whose initially threatening presence is suppressed for much of the book in a well-conceived fashion.

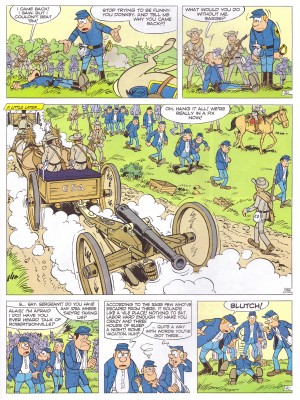

Despite this being produced for children, Cauvin doesn’t dumb down, although the reality of prison life is of necessity reduced from the brutal reality. The premise is educational in itself, and although his soldiers are Union conscripts Cauvin doesn’t demonise the Confederate forces. The cruelty of Cockroach is balanced by a lieutenant who shows compassion for prisoners, and there are just as likely to be idiots among Chesterfield and Blutch’s allies as among the opposition.

Robertsville Prison is drawn very nicely in a cartoon style by Lambil, but this isn’t joke a page material, and wouldn’t require too great an adjustment of approach to transform the script into a straight adventure. It’s a fine line, well straddled in the manner of Tintin, although this particular album doesn’t come anywhere close to matching the best of that series. Very few graphic novels do, though. A limiting element is Cauvin overlooking matters to service his plot. Very early in the book Blutch has a bullet removed from his leg, yet a couple of pages later, when not restricted by chains, he’s running around like a sprinter.

Lambil packs his battle scenes, which occur several times in the course of events and doesn’t shy from filling his smaller panels with people, frequently indicating the chaos of warfare. The whole look is busy and appealing, with the caricatures working also. Cockroach is well designed, and in the days before Homer Simpson it was extremely rare to see any protagonist in a graphic novel afflicted with male pattern baldness as Blutch is.

While some characters recur every now and then, in the manner of other European comedy albums the reading order really makes no difference. Cinebook follow this with The Navy Blues.