Review by Frank Plowright

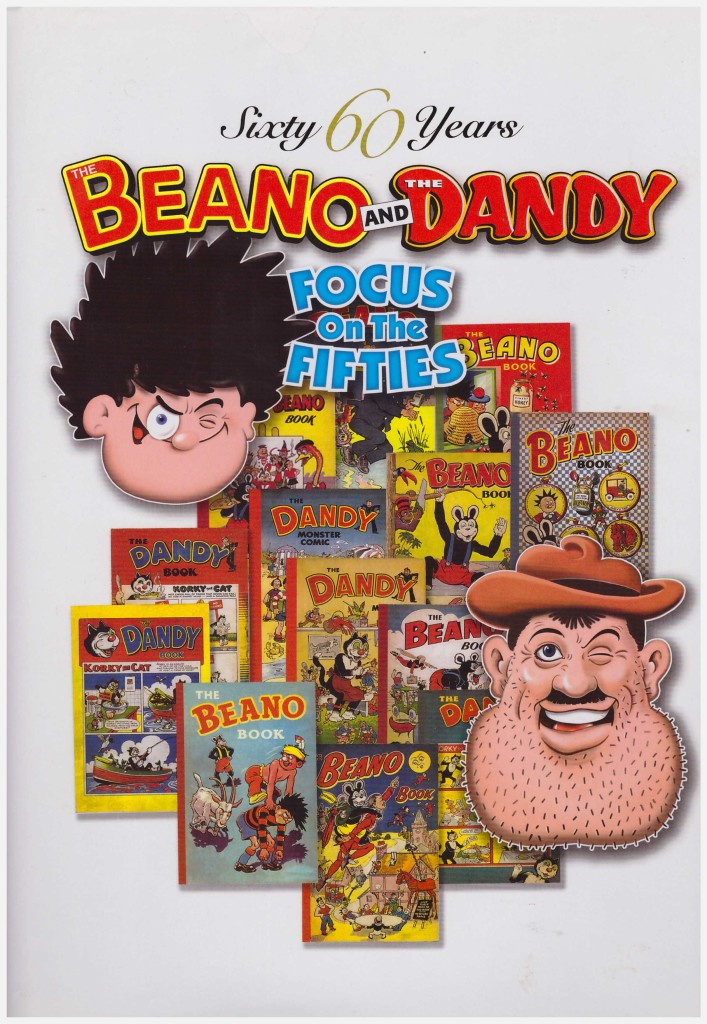

The children of the late 1930s were the first to see The Beano and The Dandy, sister newsprint comedy comics that became national institutions. The Beano is still published weekly, and The Dandy lasted until 2012, both living decades beyond the point where their titles were recognisable terms. Both publications outwitted wartime austerity, but delivered a staid and comfortable dose of comedy spliced with the occasional tame adventure strip. It took a new generation of creators joining star artist Dudley D. Watkins in the early 1950s to jump-start the comics’ golden era.

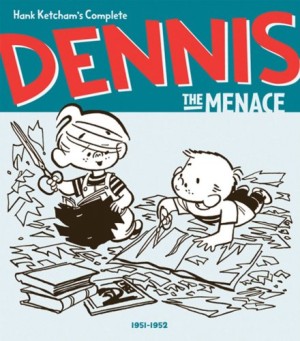

Their publisher D.C. Thomson remains a family owned company, with all the good and bad that implies. They’ve a long history of not crediting material, and this shameful negligence extends to a celebratory volume packed with the work of artists whose creations introduced in the 1950s sustain The Beano to this day. Davy Law set the pace with the wild and shaggy Dennis the Menace, oddly introduced in the same week in 1951 as his far tamer American counterpart. Over the next couple of years he was joined by the slack-jawed and rubber-limbed creations of Ken Reid, and the anarchic packed panels of Leo Baxendale. At least 111 of the 135 strip pages reprinted here are by the four artists named above (or, in the case of Watkins, possibly someone imitating his style on occasion).

This would be a thoroughly recommendable compilation were it not for the eccentric design. It seems an art student on work experience was let loose with all the tools Photoshop provided in 2004, overlaying strips atop one another, or at odd angles, imprinting others with a giant design of the iron fish or a No Entry sign. It’s grim throughout and very few strips survive unscathed. The extremely tolerant could draw a connection between the nihilistic design and anarchic content, but they’d be an idiot.

Watkins’ refined style has filtered into Frank Quitely’s work – his first published material was a Watkins pastiche – and he’s extraordinarily adaptable, delivering comedy or adventure in his precise manner. At first glance his work appears beyond old fashioned, but the compressed storytelling is masterful. His signature character, here at least, is Desperate Dan, set in a bizarre Wild West mixing in 20th century trappings.

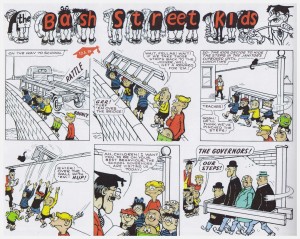

He may not have adopted the style, but Baxendale learned from Watkins. His strips are unrestrained, the kinetic art plastered with sound effects and signposts. The Bash Street Kids, Little Plum and Minnie the Minx survive to this day, with the latter having a statue of her in Thomson’s hometown of Dundee (as does Desperate Dan) where, since 2014, there’s also a Bash Street. Baxendale was also hugely impressed by Law’s work. Law was a man never satisfied, whose original pages are covered with patches, which when peeled off reveal virtually no difference to the image beneath. This perfectionist’s attitude is a complete contrast to his cyclonic personification of devilment, Dennis, another who’s survived to the present day. Reid created the most distinctive casts, with his gormless sailor Jonah a match for any Basil Wolverton grotesque and Roger the Dodger consistently attempting to put one over on his father.

A strong puritan streak ran through the Thomson heirarchy, and while they condoned misbehaving children in their strips, corporal punishment was always imposed. It appears a very odd world from the 21st century.

What survives the design is a hardback treasure trove of great children’s comics, and forms an interesting contrast with the more sedate US material of the period (and slightly earlier) in the properly designed Toon Treasury of Classic Children’s Comics.