Review by Ian Keogh

The extent of quality comics produced in Japan throughout the 20th century still seems barely tapped by English language publishers. Manga has been translated in quantity since the 1980s, yet it’s still hardly unusual to be presented with a collection of stories from someone astonishing who’s flown under the radar of English readers. It was just before the covid era that Yoshihiro Tsuge’s comics became available in English, and it turns out his brother Tadao Tsuge is equally notable.

Slum Wolf collects stories Tsuge, like his brother, largely produced for Japanese anthology Garo between 1969 and 1972, with some later inclusions published between 1976 and 1978 by Yagyō. They’re bleak examinations of human life in defeated and occupied Japan after World War II, exemplified by the opening ‘Sentimental Melody’, the content completely at odds with the comforting title. It opens in the then present of 1969 as a man recalls an emotionless transactional visit to a prostitute in 1949 before recalling a local character who survived World War II physically, but not mentally. It’s a theme explored in other stories, and essays written by Tsuge reprinted after the comics reveal how reminiscences of his upbringing in a poor area of Tokyo during the post-war era are channelled into the fiction.

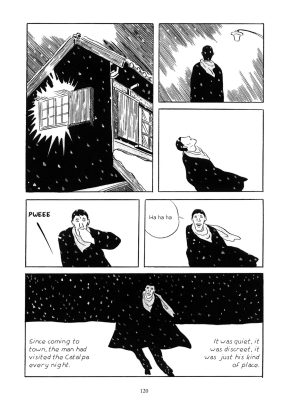

Tsuge’s stories are of ordinary people and how they react to changing circumstances. They’re nihilistic, violent and non-judgemental with a pulp aesthetic, and Tsuge’s art looks rushed and scratchy as if sketched in situ as thugs ran past or fights ensued. The scene setting is phenomenally good, but thereafter barely any backgrounds feature, as if Tsuge expects readers to place the interactions in what’s already been seen. Breakdowns are also basic, Tsuge never compressing a conversation that can be stretched, however minimal the dialogue, but the pauses and stumbling set a mood, and the dialogue is carefully selected to cultivate a noir tone.

Characters recur, most frequently Kiesei ‘Kamikaze’ Sabu, a man around whom a myth has grown, and based on a legend from Tsuge’s own neighbourhood. It’s memories of him that feature in the opening story, and we see him either directly or indirectly in several more. He’s survivor, able to handle himself, but lost. Eventually Tsuge leads us to Vagabond Plain where the dispossessed are drawn, offering a form of freedom, but never without consequences. Tsuge never completed the story, but the desolation of what he produced is more than enough.

Ryokishi Ayogishi’s sad decline is detailed over two stories, the second informing the more oblique first, which was produced almost four years earlier. He’s not a violent man, but equally tormented by a past no-one would cope with. It’s a tragedy from the first re-emergence of the past all the way to the fatalistic finale.

These are visceral, heart-wrenching stories in a powerful collection enhanced by Tsuge’s recollections of events in his essays. Further enlightening are the thoughts of translator Ryan Holmberg, contextualising time and place along with the fuller background.

Although plain and simple, Slum Wolf is also a warning about how far the spiral downwards can be, and it’s worth bearing in mind Tsuge only spotlights the abandoned with alcohol, and no drugs involved. It’s astonishing work.