Review by Karl Verhoven

To begin with, some perspective. Frederik L. Schodt’s introduction reveals Shigeru Mizuki’s hometown of Sakaiminato has a street named after him. That’s impressive enough for a comic creator (get a move on, Northampton), but this street is lined with over 100 bronze statues of his characters, and has a museum dedicated to his work. This is primarily supernatural stories, but Showa is a manga dissertation of Japan’s recent history.

Schott’s introduction further reveals the title as that of an era, spanning the ascension of Hirohito to Emperor in 1926, four years after Mizuki’s birth, until 1989 when Hirohito died. This first volume reaches the European outbreak of World War II, during a transformative and turbulent period.

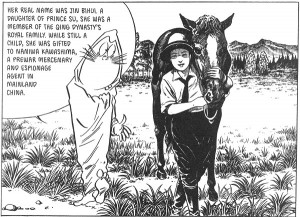

Mizuki counterpoints the national events with memoir and anecdote, employing contrasting art for the two strands. Historical events are delivered in a studied realism, often copied directly from photographs, or incorporating them, while assorted cartoon everymen comment on events. Most prominent among them is Nezumi Otako, here not the deceitful trickster nationally known in Japan from Kitaro, but Mizuki’s narrating replacement. Cartooning is also employed for the biographical sections, but this is a restrained style for those used to manga forms, lacking the speed lines and exaggerated emotional depiction. Mizuki often places his simple cartoon avatar on backgrounds rendered in intensive detail, providing an odd contrast.

Showa is an immense achievement. To most outside Japan the historical shifts in society prior to World War II won’t be widely known, and either Schodt or translator Zack Davisson provides comprehensive annotation. Despite a reprimanding tone, culturally sensitive in Japan, applied to home suppression and overseas expansion, the presentation of early political events is very dry. It’s roughly a third of the way through the 500+ pages that Mizuki depicts the social consequences of these policies, and the historical narrative erupts in horrifying fashion. The scale of deprivation endured by ordinary citizens is scarcely believable to the 21st century Westerner.

The rise of right-wing militarism began as Japan reeled from the effects of a 1923 earthquake that killed hundreds of thousands and left greater numbers homeless, and increased during the great depression that ended the decade. Simultaneously a law protecting Japan’s cultural identity was ruthlessly employed to crack down on social dissent. This eventually led to an official dictat that “happiness lies only in absolute submission to the Emperor’s will.”

Among the atrocities later revealed is how the military had no compunctions about arranging for the killing of Japanese citizens in China to further their nationalistic cause. Such was the power of the authorities that a nearly successful coup attempt in 1932 was never mentioned in the newspapers of the time. A more successful military insurrection in 1936 resulted in the deaths of several ministers, so was reported, but quashed within days. As Mizuki was growing up during this period his childhood recollections provide a much-needed antidote to the otherwise depressing plunge into fanaticism. He and his friends walk ten miles to sample a new treat they’ve heard of: the donut, his habit of clipping newspaper headlines, the fights with other neighbourhood kids and his early incompatibility with work all entertain.

“It’s a shame, but people rarely make the difficult choice of leaving things alone” says Mizuki’s stand-in Otako. While this is noted midway through, it applies as a summary of the period.

In Japan Showa was published over eight volumes from 1988, but Drawn & Quarterly have repackaged them as four books on pulp paper, reading from back to front and right to left in traditional Japanese manner. The next book covers 1939-1944.