Review by Frank Plowright

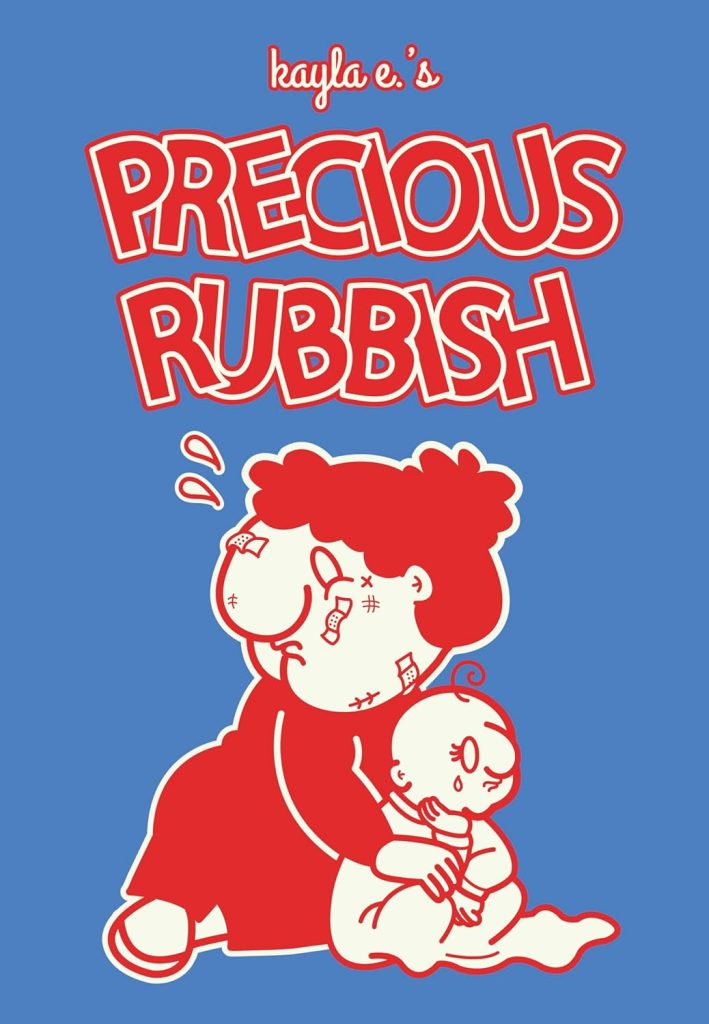

Precious Rubbish is created to resemble the trappings of children’s publications, with Little Lulu the most obvious influence on the strips, but events are also related via puzzle pages, paper dolls and adverts. The thought applied to the design is immense, yet this disguises an extremely bitter and challenging pill. For all the decorative talent, this is the testament of a child growing up in appalling circumstances, neglected by her parents, abused by her brother and alcoholic before puberty.

It’s the childhood experiences of author Kayla E., some of which she can’t recall, noting in one case games of gripping the soap in the bath while her father bathed her. She can remember the playful name of Soapy Dopey, but her mind only encounters a blackness when attempting to recall specifics. What she can recall is an absolutely horrific catalogue of systematic abuse with occasional extreme religious overtones. This is presented in consistently innovative ways, such as fifteen recollections of a grim home life as markers on a board game causing a player to move back several spaces. It’s an expansion of Chris Ware’s visual density, and events being related through the accessories of childhood means they’re not visually explicit, yet those trappings accentuate the vulnerability.

Beyond the memories that don’t resurface, not everything is clear in a narrative that’s never linear, while splitting events into short and separated sections allows for focus, but not continuity. It means readers have to join some dots outwith the join the dots puzzles and make the referential leaps to previous disclosures. Furthermore, incidents from the past are overlaid with additional commentary, sometimes calming routines developed for adversity and sometimes religious exhortations. Therapeutic and behavioural terms are referenced with hindsight

Make no mistake, a distancing process means the innovation can be admired, but the intensity, rawness and density ensures Precious Rubbish is extremely difficult to read, with the obvious follow-up thought being how infinitely worse the content was when actually experienced. The most striking aspect is the isolation. There was no-one that the young Kayla could turn to. Everyone in her life seems to have added to her persecution. The tragedy appalls.

A full selection of artistic references reveals the strips are largely adapted from 1940s and 1950s children’s comics and repurposed to serve narrative needs, while other citations are Biblical, notably ‘The Book of Job’, or refer to conversations.

Precious Rubbish has received innumerable plaudits for both presentation and honesty, and rarely has the adage of suffering for one’s art been so appropriate in the comics world.