Review by Graham Johnstone

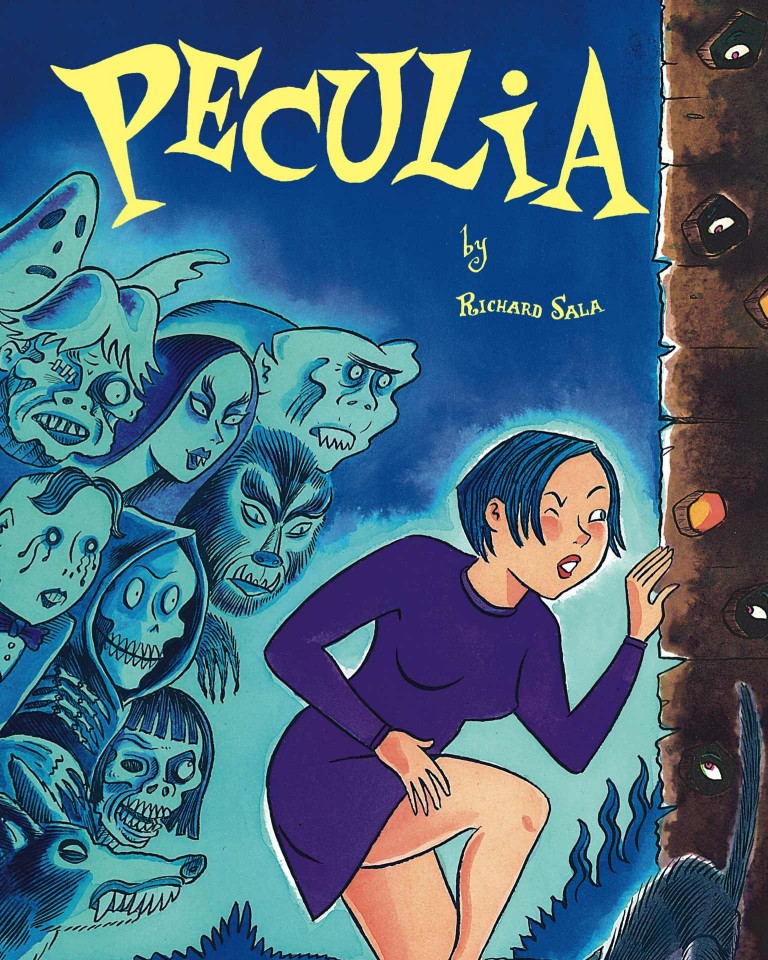

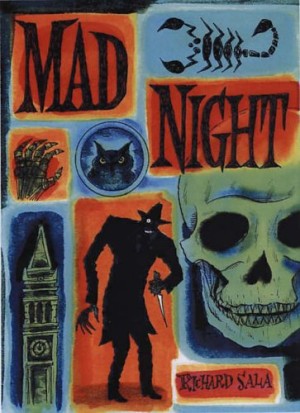

Richard Sala has created a niche of post-modern gothic. Around the turn of midnight… sorry the turn of the millennium, he produced the Evil Eye series for Fantagraphics, collected in Mad Night and this volume, Peculia.

The distinctiveness of Sala’s work, though, can disguise his range, and comparing the two series from Evil Eye is illuminating. Mad Night is an intricately plotted epic, whereas Peculia is a series of self contained stories, albeit with some development of character relationships over the series. While both have young, female, leads, Mad Night’s Judy Drood is a detective pursuing the solution to a mystery, whereas these short stories ‘happen’ to Peculia. The latter is in the literary tradition of the flâneur, a strolling observer, transposed by Sala from the boulevards of Paris, to the inner Europe of the Brothers Grimm. Judy Drood hunts down and interrogates a parade of grotesque menaces, unlike Peculia who simply chances upon them as she saunters through a haunted forest, and is tempted into isolated inns, and suspicious shops.

These are page-turning romps, with pacy storytelling and snappy dialogue, but also with literary depth. They may be familiar in the set-up, but they’re funky in their twists, and refreshing in their turns, mischievous metafictions citing and subverting gothic horror tropes. For example, in ‘Ambrosia’, Peculia flees spying rival Justine, into the kidnapping arms of a gentleman (stove-pipe hat – tick, mutton chops – tick) seeking Peculia’s ‘help’ to resurrect his eponymous wife. This, of course, does not go to plan. Peculia saves herself accidentally, by correcting his misapplied incantation. It results in Ambrosia’s untimely resurrection as a festering corpse, who misunderstands her husbands intentions with Peculia. Sala’s comics are understandably compared with Charles Addams or Edward Gorey, but they’re as much like Angela Carter’s feminist re-appropriations of fairy tales because Sala applies modern liberal sensibilities to this material. The Sala turn, in ‘Ambrosia’, is that Peculia yearns for such romance and passion, but rather than conform to gender victim stereotypes, she plants a kiss on the surprised Justine. That’s a lot of twists, turns, and re-appropriation packed into just eight-pages.

There are layers of intertextuality. Peculia may seem a horror movie ingenue, but her severe bob haircut evokes the emancipated flappers of the Roaring Twenties. In the opener, Peculia toys with her cereal with the listless ennui of Goethe’s Young Werther. The book could have been alternatively titled ‘Alice in Peculialand’ as the swarm of identical children could be Tweedledees with Chesire Cat smiles. Furthermore, Peculia’s butler Ambrose proves the Jeeves to her Wooster, with many tales ending with one of his comically implausible rescues. There’s truth, then, in his publishers’ blurb that Sala’s work is “like nothing, but like everything.”

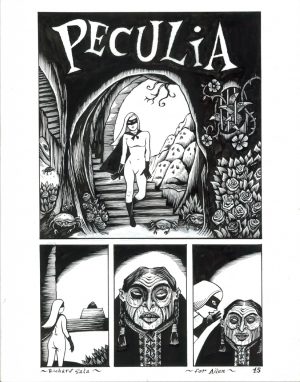

Sala’s art is both historic and modern. His feathered inking and heavy blacks evoke woodcuts, as might be found illustrating gothic novels. Yet his skewed perspectives, flattened space and oppressive angles are thoroughly modern. Similarly his rendering acknowledges the modernist idea of his ink lines asserting their reality as lines on paper. In particular, he evokes the 20th Century reappropriation of the woodcut by German Expressionism, and its cinematic expressions, particularly The Cabinet of Doctor Caligari. When we best see Sala’s folk-historic Brothers Grimm sets and denizens, it’s through noticeably modern widescreen tracking shots of a strutting Peculia. Similarly Sala’s treatment of figures is rooted in the introduction of simplification into European art.

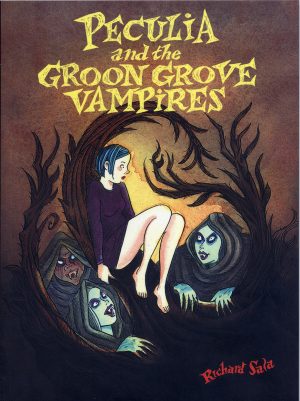

In their composition, rendering, and immersive mise-en-scene, the best pages here rank with any in the medium, and these witty shorts are among Sala’s best. Peculia returns in Peculia and the Groon Grove Vampires.