Review by Frank Plowright

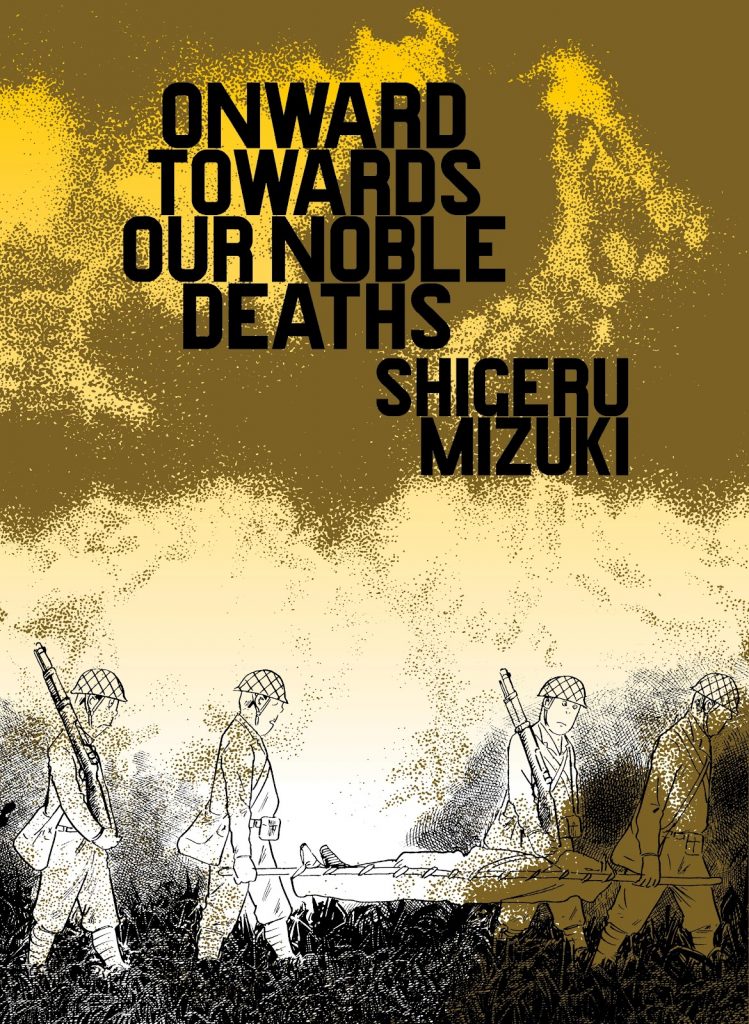

Plenty of atrocities follow in Shigeru Mizuki’s fictionalisation of his World War II experiences fighting for Japan, but it’s worth drawing attention to an opening horror. The story opens in 1943, with thousands of Japanese platooned on a small Pacific island. One brothel serves everyone and we see a vast herd of soldiers outside and a woman’s plaintive shout from within that her body can’t take any more. It’s followed by the lyrics from a song sung by Japanese prostitutes of the time bemoaning their circumstances.

Mizuki’s alias is Maruyama, just one among many hungry, ill and demoralised men expected to sustain themselves on patriotism, and regularly beaten by commanding officers. While the satirical approach he takes could be seen as disrespectful, it helps to highlight some ridiculous situations and remove some horror from others, such as his witnessing an almost starving comrade die choking on a fish he’s caught.

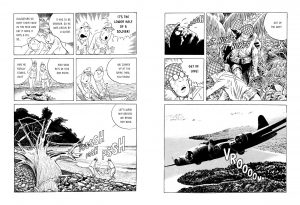

As on other projects, Mizuki draws simple, often exaggerated cartoon figures on exquisitely rendered pen and ink backgrounds, and if not familiar with his methods it takes some getting used to. The cartooning, though, allows for an expressiveness. The biggest contrast is the tragic ending, where the inevitable occurs, and Mizuki memorably shifts to a more realistic style over several harrowing pages, not the first time he uses detail to depict devastation.

Throughout Mizuki underlines the futility of war, and the monumental stupidity of the officer class who insist on trivial matters of protocol in the face of starvation and possible death from any side, and who think soldiers with malaria will undertake a suicide charge. Thankfully Mizuki has a steel trap memory of the humiliations he and others endured when any day could be their last on Earth. He’s very observant and caring in other respects, and the only time his insistence on detail really works against him is with the large cast. Thirty of them are illustrated on a guide, but it’s difficult to remember characters who drift in and out of such a long work. However, he’s seemingly being true to dead comrades in presenting their far from noble deaths.

For all the tragedy there are many funny moments, some coarse, although some bleak, such as the fate of a major keen to lead a suicide charge. That’s somewhat of an obsession toward the end, most unforgivably men being sent to their deaths just because a message has already been sent to headquarters announcing just that. One potential victim is asked if his worm’s life is really so precious and told he shames his country by valuing it. By then there is no humour only anger, but Onward Towards Our Noble Deaths remains haunting and memorable to the end. It’s designed to act as a warning, and succeeds while also depressingly showing what decades of cultural propaganda leads to.

An introduction from Frederck L. Shodt sets the scene, and detailed explanatory notes are supplied, along with Mizuki’s afterword and an interview with him. Mizuki would revisit his World War II service again over four volumes of Showa, during which he places it in greater historical perspective, but Onward Towards Our Noble Deaths is a compact masterpiece.