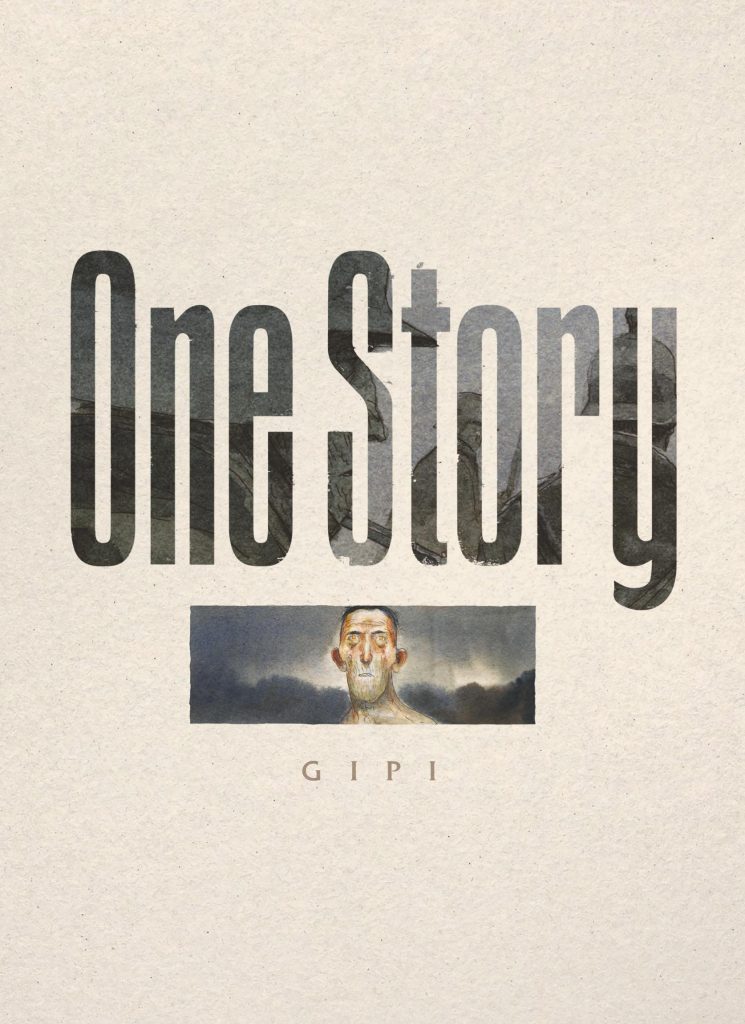

Review by Ian Keogh

Gipi’s One Story is at the upper end of conceptual innovation, at the start told so deliberately awkwardly that it’s going to be offputting to many readers. It switches between hallucination and reality, and between different time periods, while pictures seem not to be connected to the captions laid over them. Intended as disorienting, after twenty pages Gipi reveals what we’ve been experiencing is Silvano Landi’s state of mind. He’s a nationally known writer found alone at the beach in a disturbed state and committed to a psychiatric institute. Recurring in the sketches he produces are a petrol station and a tree.

What will hold interest that might otherwise rapidly slip away is Gipi’s remarkable art. There’s no doubting a master’s hand at work from the spontaneous delicacy of the linework to the vibrancy of the watercolours, the illustrations are attention-grabbing. Beguiling portraits mix with exotic landscapes, every drawing something to be admired.

While they’re captivating the reader, Gipi gradually unwraps his story. Landi has always been distanced, far more likely to become excited by revelations from the past than by what’s going on in his immediate family, and he has a particular interest in letters revealing his great-grandfather’s near death experiences in World War I. There’s an irony to this as the old letters reveal the conscript’s abiding love for a family he believes he may never see again, while the person reading them, the result of a family line that continued, is oblivious to his own family falling apart. Phrases that were introduced earlier in the book are given new context when later repeated, but some moments remain beyond rational explanation. While we can understand how Landi experiences the past in his head, how can he simultaneously fixate on his future?

A futher irony is that the Landi of World War I is almost beatified by his writer descendent for the beautiful language used in letters sent home from the front, but his true motivation is to do what he must to survive, and the ultimate revelation is how unpalatable that can be.

Anyone ought to be able to appreciate the artistic beauty of One Story, but Landi’s existential crisis is less universal. It’s a graphic novel for a select audience, not a wide one.