Review by Frank Plowright

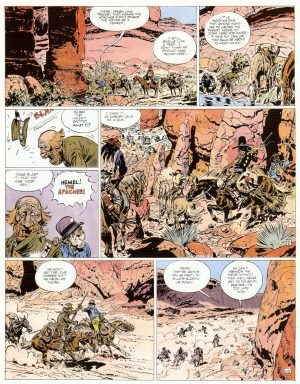

Compared with the four volume series of Lieutenant Blueberry, and the epic ten volume saga that followed, beginning with Chihuahua Pearl, the two French albums translated here are relatively compact. Produced for serialisation in 1969 and 1970, the opening sees Blueberry dispatched to maintain law and order in the Arizona mining town of Palomito in 1868, accompanied by Jimmy McClure, a man prone to a drink, and as ever, as a much a hindrance as a help.

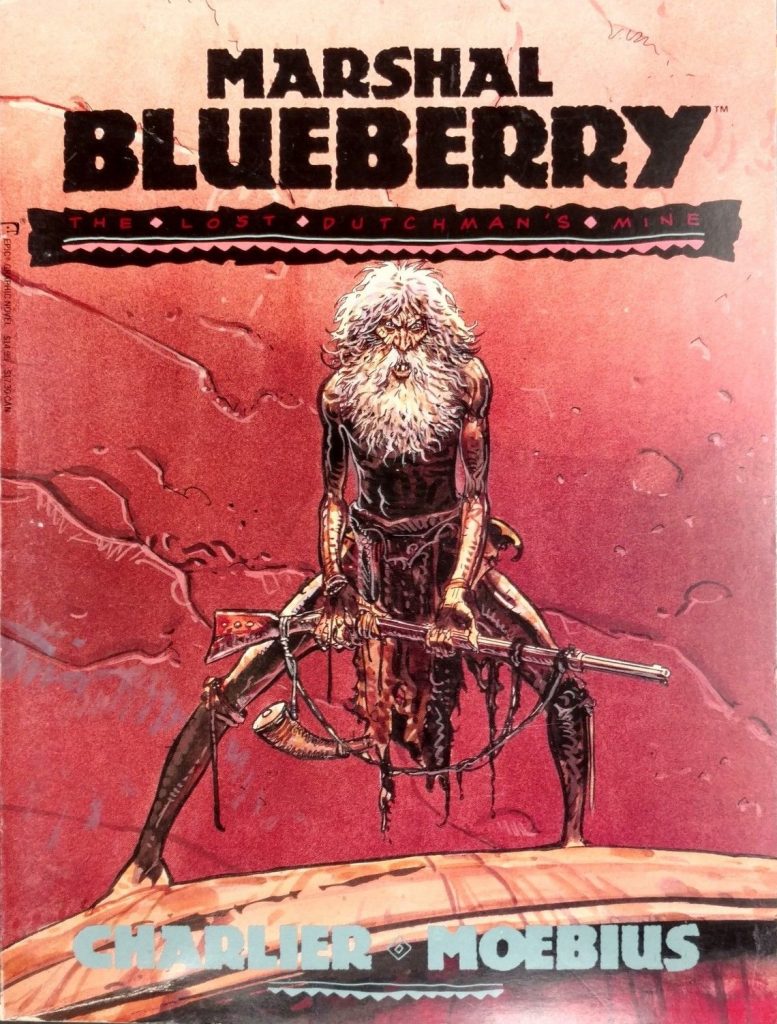

As was common to the Blueberry series, the starting point for The Lost Dutchman’s Mine was the actual legend of a lost mine in the Superstition Mountains, a legend that inspires treasure hunters to this day. The Dutchman in Jean-Michel Charlier’s story is a conman who may or may not just occasionally masquerade as Dutch, who’s left a trail of deceit and murder across the state, resulting in plenty of enemies. He’s a master at manipulating the gullible, and does so by dangling his supposed knowledge of a massive gold mine in front of them. The awkward aspect is that the Superstition Mountains are regarded as sacred by the Apache Nation, and they guard them zealously. Additionally, the Dutchman manages to cause all sorts of trouble for Blueberry, some of it life threatening. He’s a magnificent creation, devious and sadistic, and the entire story is propelled by his ability to change his account and switch allies at every stage that seems to his advantage.

A remarkable aspect of the Blueberry series is how it’s an accumulation of Western standbys, yet it’s consistently fresh and thrilling. There’s an audacious manipulation of convenience and cliché, and Charlier never demeans or downgrades Native American culture, all of which makes the series very readable today. A large part of that is also due to the stunning work of Jean Giraud, packing ever more panels onto the page to accommodate the plot, yet never having them seemed cramped. There was no relief for him when the story moved from the crowded town to the open desert for the concluding episode, as that’s packed with chase scenes, which mean horses, and plenty of them. Giraud’s fantastic at drawing them, whether in action or at rest. Including any pages from late in the book would supply spoilers, but toward the end Giraud’s able to focus on single characters and the art remains magnificent.

As with all Westerns, there’s a certain inevitability about the ending, again very abrupt, but getting there is a fantastic trip, as the cast who survived the opening episode face the ghost with the golden bullets. It’s common to Charlier’s stories that he’ll spend considerable time away from Blueberry, studying those he orbits, and building tension by letting the readers in on what’s being plotted, but he varies that here for more of an ensemble approach. Charlier considered this his favourite Blueberry story, and it’s immensely satisfying.