Review by Ian Keogh

Shoko Komi is a pretty high school student who would seem to have everything going for her, but overwhelming social anxiety leaves her unable to co-exist in a normal way. The first of her classmates to recognise this is Hitohito Tadano, himself tending to gushy over-expressing to disguise his own awkwardness, while her other classmates consider her aloof and mysterious.

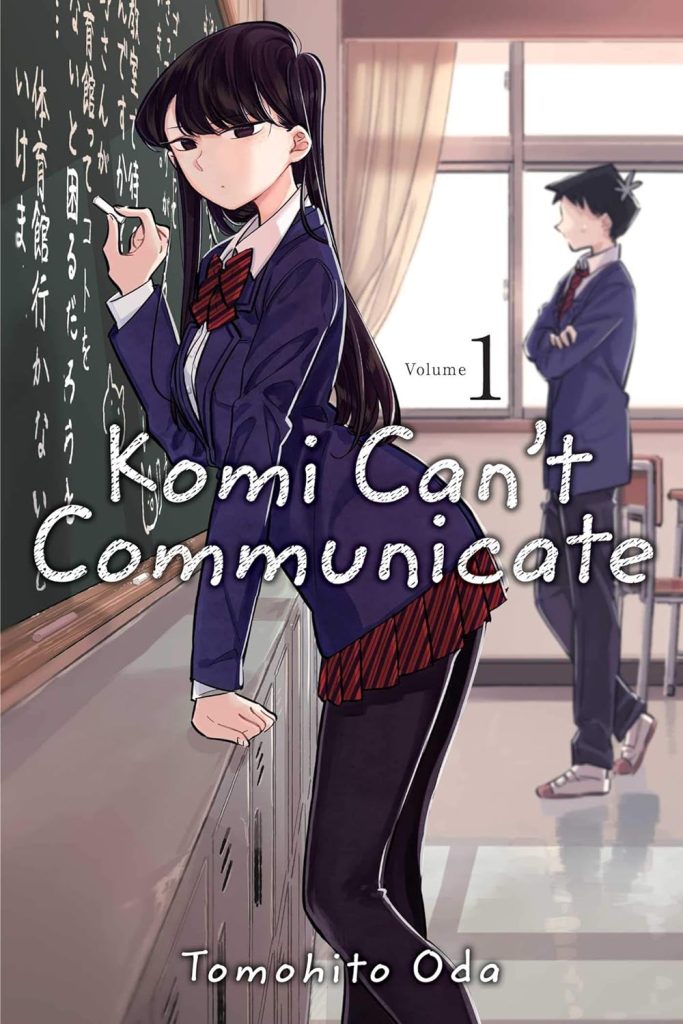

Creator Tomohito Oda is also mysterious, preferring anonymity. However, certainty about her creative skill arrives early when Tadano breaks through to Komi and she’s able to express herself and her fears via writing on a blackboard. It’s a heartbreaking emotional rush, and an immensely powerful scene, yet only forty pages in, raising anticipation for the quality of what’s become a long running series. It also establishes the way of drawing Komi, with a fixed expression on her face.

There’s a realism to events. Having broken through, Tadano assumes the following steps will be easier, perhaps in the manner of an addict needing treatment first needing to admit their position, but the following ‘communication’ (the term Oda uses for chapters) clarifies the shortcomings of that presumption. Heavy among them is Tadano’s own lack of friends.

The longer this opening volume continues, the more obvious it becomes that Komi Can’t Communicate has an overriding theme of judgement, as each new character arrives with their own set of issues. Tadano can speak to others, but his nervousness means he’s not the greatest communicator either. The confident Osada has decided she’s a girl since Tadano last knew her and is extraordinarily popular, while Agari is small, overweight, requires glasses and has self-esteem issues. She’s infatuated with Komi, one of many students who believe her lack of speech represents a superior attitude. What begins as Tadamo’s project to make Komi a hundred friends involves them all, and others besides.

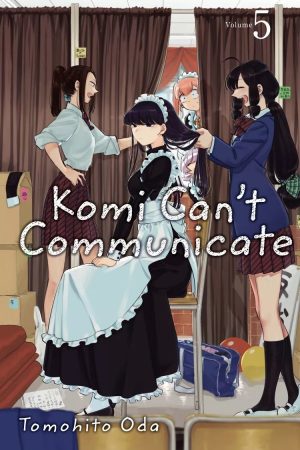

Oda’s artwork is unusual for modern day Japanese comics, or at least those translated into English, as it deals with characters from distance, which may be intended as a clever visual metaphor. People are usually shown as full figures with completed and populated backgrounds, apparent in the sample art. That also displays the frequently used technique of explaining the world as seen by one person, then showing how it’s experienced by another. Komi is generally involved, but not always.

In an individual way Komi Can’t Communicate presents existential trauma, and on the basis of the opening volume, this really is a smart series for doing so with considerable humour and charm. Oda opens the door to communication in multiple forms while simultaneously ensuring readers are forced to consider their own attitudes to people around them. Bring on Volume 2.