Review by Karl Verhoven

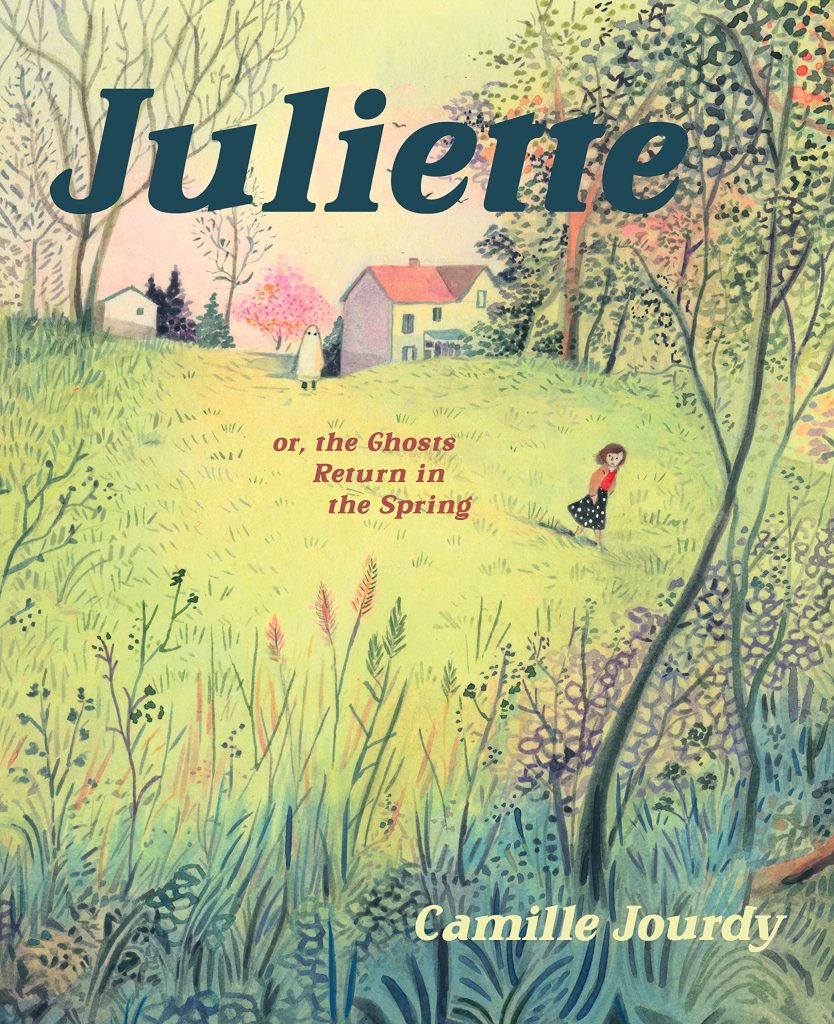

Juliette is first seen taking the train from Paris back to her far smaller home town. She’s staying with her father who’s emotionally distant, and from there Camille Jourdy gradually builds a suburbia encompassing both forgotten past and essential present. At the start it seems a soap opera following multiple characters, but they eventually connect in cleverly conceived ways, not least because Jourdy explores lives and concerns while delivering consistently naturalistic conversations. These are the disagreements and daily shorthand, with translator Aleshia Jensen deserving credit for their English realism, but Jourdy has a deeper agenda.

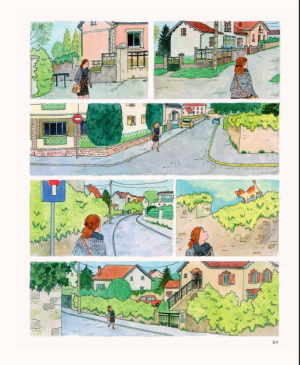

Observation is Jourdy’s stock in trade. It’s apparent in every small, perfectly formed panel, whether it depicts an emotional response during conversation or the details common to every town, down to the design of bus shelters and garden fence variations. The observation extends to the story, be it the playful scenario of Juliette’s sister meeting her lover dressed as a rabbit – he runs a costume shop – or the pointed remarks with which family members stab at each other. While others can be full on in proclaiming their opinions, Juliette keeps much buried within, only occasionally offering her thoughts, usually when caught off guard. “Everything feels different”, she explains, “like there’s this curtain of fog between me and reality”. And is she a hypochondriac or possibly depressive?

Most of Juliette is produced in delicate linework for small panels, Jourdy’s people not far removed from those drawn by Posy Simmonds, but scenes can be punctuated by watercolour paintings. These are equally detailed, and resemble a slightly restrained Beryl Cook illustrating moments from the works of Alan Bennett.

Jourdy never names Juliette’s home town, bestowing a universal experience, and she ensures readers become so caught up in the family dynamics that the core story slips in stealthily and unobtrusively. Juliette’s interactions with family often become stressful, and she finds herself spending more time with the eccentric Georges, who rents part of what used to be her family home. His is a shambolic life with too much time spent at the pub, but he listens to Juliette and Jourdy subtly manipulates readers into investing the desire that something comes of their time spent together. She also has a bombshell to drop, one that explains much about the family being dysfunctional, yet smart writing ensures that’s not actually the crisis point, arrived at through a farcical situation arising from Juliette’s sister’s extra-marital activities.

Jourdy has published around a dozen graphic novels in France and based on the smart sensitivity of Juliette, it’s astonishing her work hasn’t been available in English before now, but perhaps hers has been a career building toward this. For all the charm, it’s also clear throughout that Jourdy’s not greatly sentimental. A couple of shocking moments derive from that, and it ensures suspense is ingrained until the final pages. Juliette is rich, dense, and melancholic with enormous attention paid to detail in all its forms. It’s a graphic novel to treasure and to re-read.