Review by Karl Verhoven

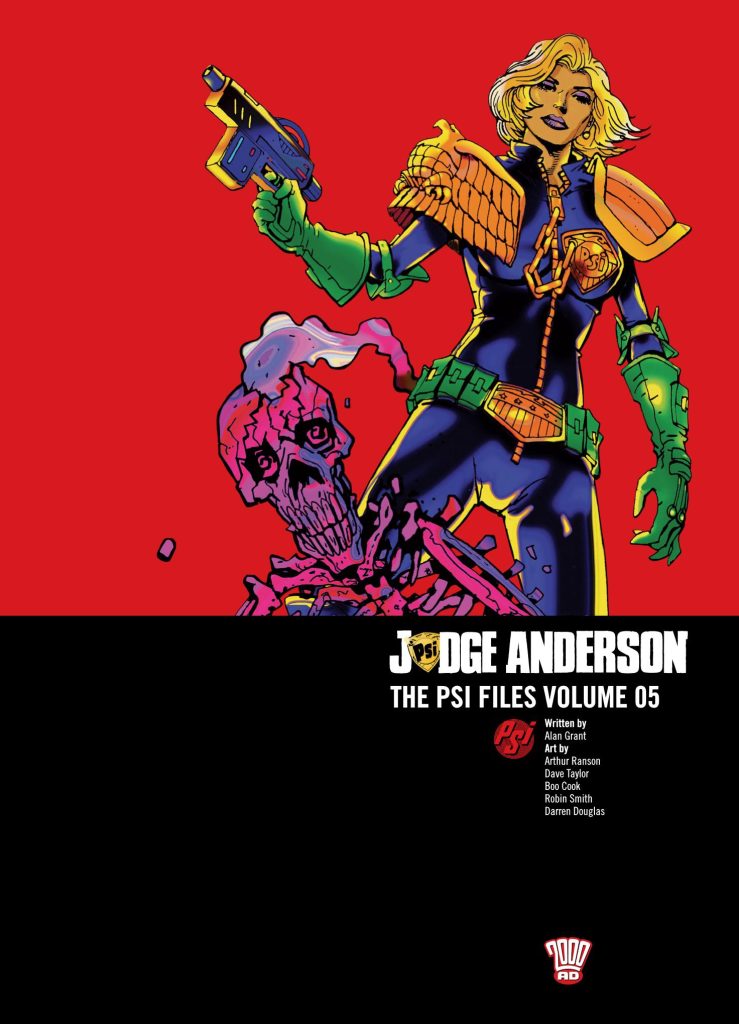

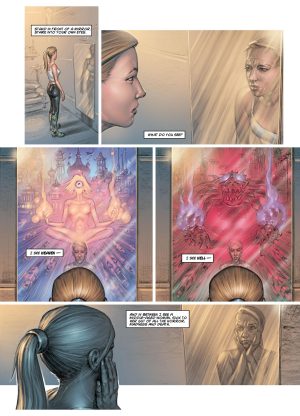

Boo Cook’s sample art is the final page of the final ongoing Judge Anderson solo series from Alan Grant, completing a journey that lasted over twenty years in both a literal and metaphorically reflective way. Read the story preceding it, and that page is beautifully understated. Grant’s primary artistic collaborator bows out with ‘Lucid’, which opens the collection. Arthur Ranson’s art has been so stunning over so many stories that it’s tended to overshadow the solid quality of Grant’s plots, and although there are a few touches here and there of Ranson no longer at his peak this is still mightily impressive art, bringing through the terror of an invasion from beyond. Grant surprises with a clever reason for the problem and provides a rapid solution when it’s deduced.

With Ranson, Cook and Dave Taylor responsible for most of the illustration, this selection is another art fans delight, Taylor announces himself with an incredibly detailed spread of Mega-City One’s architectural eccentricity as seen from above. His artistic gift is scenes of robotic city blocks coming to life, one of those clever moments Grant’s so good at where he’ll have you considering whether or not the villains of the piece actually have a point. “Imagine! Mega-City One will be the first of a new breed”, claims an insane architect, “the first self-conscious city”. The artistic tip of the hat via Kev O’Neill Block is great, and Grant supplies him with several more artistic treats.

Cook makes his debut on a tale of disruption to a facility allowing people to live out their fantasies by creating VR worlds in suspended animation. He’s a work in progress, with plenty of rough spots on his first story, but these gradually become fewer and fewer as his almost two hundred pages turn, the stylistic quirks coalescing into a defined style and the messiness of earlier stories gone.

This is a less spiritual selection than provided in earlier volumes. The big questions are shelved, but Grant’s able to give food for thought over a variety of subjects while always prioritising an action thriller. Ecological concerns, a group rejecting city values and the causes of social ills come up in passing. There’s variety, both in terms of genres and their sub-classifications, but a couple of stories prioritise Anderson as an action Judge, and although her personality shines through, it sidelines much of what makes her unique.

The collection ends with two shorts. Robin Smith’s art is stiff on a trivial look at Anderson as a housewife instead of a Judge, seemingly dashed off by Grant who’s heart wasn’t in the concept. ‘Horror Comes to Velma Dinkley’ is much better, a showcase for some fine art from the very promising Darren Douglas, and a reinforcing of the Judge system’s hypocrisy.

While not everything in this collection is solid gold, it never drops below readable, and a couple of stories are up there with the best of Grant’s run. Considering that run extended over twenty years and involved some magnificent art, it remains under-rated. Anyone who likes their action with a horror twist and has never taken a look at Anderson’s solo selection should investigate immediately.