Review by Ian Keogh

If Jack Kirby’s stories can be distilled to an essence, the primary motivators are conceptuality and energy. Kirby’s comics pulse with ideas, and he prioritised moving his story forward at pace, which often left the dialogue as an obligational afterthought as one amazing idea was followed by the next, some explored, others just considered in passing as he surged onward. Thematically, much of his work was almost biblical, dealing with higher powers and questioning humanity’s purpose and destiny, offering plenty of alternatives. No-one can truly speak for another, but it’s difficult to imagine Kirby being attuned to the decompressed superhero stories of the 21st century.

All this is relevant when considering a collection of tributes to Kirby on what would have been his hundredth birthday in 2017 (collected in 2018), featuring the work of other writers and artists on the characters he created for DC, either in the early 1940s or the early 1970s. Kirby’s one time assistant Mark Evanier writes an introduction to every chapter, and highlights Kirby’s belief that being inspired by him was fine, but expanding on his work rather than repeating it was essential. Not everyone’s taken that on board, and some stories approximate Kirby’s approach without an iota of originality. It’s interesting then, that Howard Chaykin’s work stands out. He makes no attempt to mimic Kirby’s artistic style or layouts, but takes his kid gang casts and makes them work to his own parameters, flitting around the world in the 1940s while looking ahead to the 1950s. It’s also difficult not to read in comments about those today who’d hijack patriotism to their own ends.

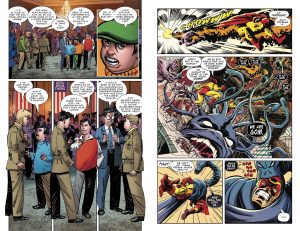

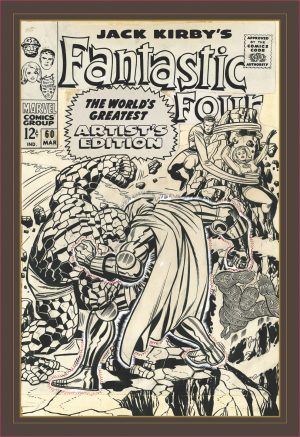

Several artists attempt to work in Kirby’s style, and that even the immensely talented Mark Buckingham can’t quite pull it off (too delicate in places) indicates it’s not just a matter of squaring off the fingers, thickening the lines and exaggerating the poses. Keith Giffen’s simple story for Buckingham is an accurate pastiche, with the nice touch of having the 1940s Manhunter himself hunted for his excessive methods. Jon Bogdanove includes a nice photographic collage as homage, 21st century photoshopping simplifying a task Kirby achieved by literally cutting and pasting. It’s Bogdanove (sample art) and Dan Jurgens taking on Sandman who come the closest to a Kirby story in look and intent, although Mark Evanier and Scott Kolins are also creditable, with Kolins more his own artist and Evanier’s take on Darkseid imposingly malign. Steve Rude accomplishes the impossible by echoing Kirby with art that’s still recognisably his own on a Demon story, but then that’s a trick he’s managed before. The same could be said for Walter Simonson, whose Orion series channelled Kirby. He returns to a younger Orion here with some spectacular art.

Part of the reason that stands out, though, is because the spectacular is in short supply. However well intentioned, all too many contributions are ordinary. The reason Kirby is being celebrated is because he was a towering conceptual genius, and to expect 168 pages matching his peak is setting the bar way too high, but too many creators have jumped at the chance to honour an influence without contributing originality. They skirt around what Kirby did without producing anything anywhere near as memorable, and that’s disappointing.

Further disappointment is the absence of Kirby’s own work on the characters used that accompanied these stories when issued individually. It’s a strange celebration of a life’s work that only includes the single page by the person concerned.