Review by Frank Plowright

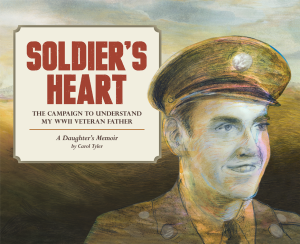

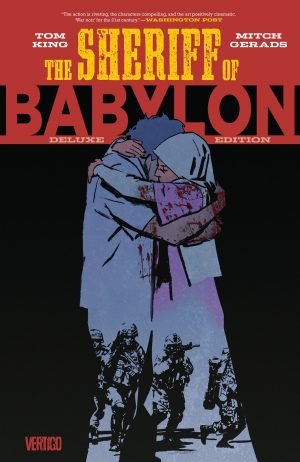

Among those who have served in the armed forces it’s understood civilians have no real idea of what they’ve experienced, and only a fool would attempt to apply the maxim of not being a carpenter yet recognising a wobbly chair. That being the case, letting former soldiers tell their stories in their own words is the nearest we’ll come to any understanding.

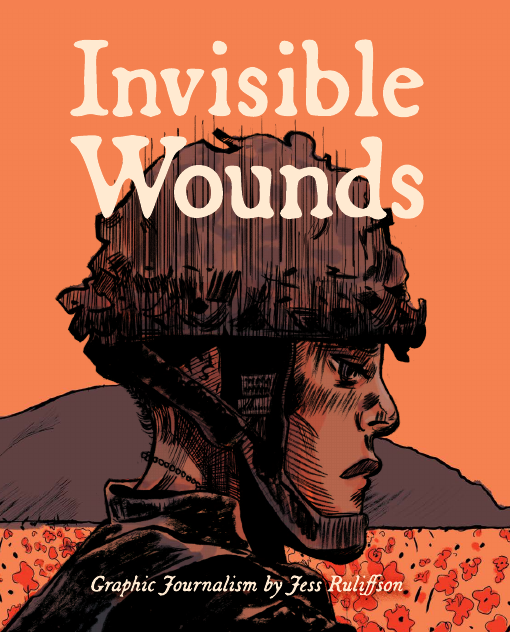

Jess Ruliffson’s technique is to break down interviews containing the recollections and observations of a dozen former soldiers into roughly twelve page sequences. A broad range of experiences are presented, no two alike, although it’s common that young people don’t realise what they’ve signed up for, as is brutality during training and service, and trauma. However, there’s also considerable insight and sympathy transcending expectation. It’s beyond Ruliffson’s remit, yet it would be interesting to know how representative these stories are with regard to general attitudes among those who’ve seen action.

Ruliffson’s interviewees certainly cover a lot of bases regarding orientation and ethnicity, and while most subjects talk about serving in Afghanistan and Iraq, some never saw time overseas. Atrocities are related and regretted, even while acknowledging some killings were necessary to save lives, but almost every subject notes something surprising. In Jordan Blisk’s case it’s the jaw-dropping requirement for every student at her school to take a military aptitude test as part of career placement. Maurice Decaul’s recollections are among the more aggressively stated, yet he became a writer. Christie Turner’s entire story is one of reprehensible treatment of someone who should have been supported. Matt Klein talks about being blown up. Three times.

Keeping the art plain ensures the focus is on the stories being told. No-one here is a gung-ho maniac, and all at least started out genuinely believing they were serving their country in time of need. Almost all interviewees address life beyond service, the difficulty of transitioning and how some people can’t. Thoughtful pagination sees Phil Klay’s introspective assessment of post-service life close Invisible Wounds. In common with others he notes conversations where people enquire about the worst and then don’t know what to say. He concludes people are interested in war, but there are aspects they don’t want to know about, and the recollections of most here are likely to generate unease for not fitting the movie fabrications. If Klay is right, and with his experience there’s no reason to suspect otherwise, Invisible Wounds should be on every school library shelf to provide a truer picture. Maybe Fantagraphics could start by sending a copy to Blisk’s high school.