Review by Frank Plowright

How to Make a Monster is outsider artist Glenn Pearce interpreting the written recollections of Casanova Frankenstein and transforming them into a form of illustrated scrapbook memoir. There’s no mention of Frankenstein adopting his alias from the Mystery Men movie.

In 1981 Frankenstein was 13, yet when puberty hit his Chicago classmates transforming them into testosterone-fuelled aggressors he was left behind and isolated, unable to understand his social exclusion. His first crisis comes to a head when a smaller kid from the neighbourhood challenges him to a fight, which he’s losing when it’s broken up by an adult. The events leading up to and following the incident have left an indelible scar, and Frankenstein is able to recall them in almost forensic detail occupying over a quarter of the book. The unsympathetic response from his parents is heartbreakingly ignorant, devoid of understanding.

The memoir speaks for many in testifying how tormented school experiences can be for children. The perceived wisdom is that those who don’t fight back are forever destined to be victims, but that’s only because so many people and systems have failed children. In Frankenstein the result is an understandable bitterness sometimes manifesting in generalisations such as black culture being entirely motivated by materialism

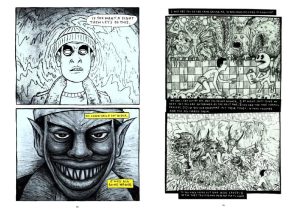

However, the remarkable aspect of How to Make a Monster is Pearce’s remarkable art, not the writing, which is observational and heartfelt, but far from the writers namechecked on the back cover. The art is all over the place, but attention-grabbing for its exaggeration and disturbing qualities, and weakest when attempting traditional comics continuity following one panel to the next. During those sequences it’s a matter of waiting for the next audacious step into artistic freedom. In one panel Pearce will channel Big Daddy Roth, and in the next Peanuts, or switch from effective portraiture to demented scribblings. Creative visual metaphors begin with Frankenstein’s tormentors depicted as devils and become more impressive, such as the ideal virginal woman trapped in a doll’s box hammering with her fists against the transparent plastic film.

Unfortunately, there’s not enough of that, and as grim as Frankenstein’s younger life was, at times How to Make a Monster reads as written in response to a therapist’s request to recall pivotal circumstances as exactly as possible over a period of weeks. It will touch a deep chord with some people and while you’d have to be divorced from humanity not to have sympathy this is unlikely to be a book anyone will return to for anything other than the art.