Review by Ian Keogh

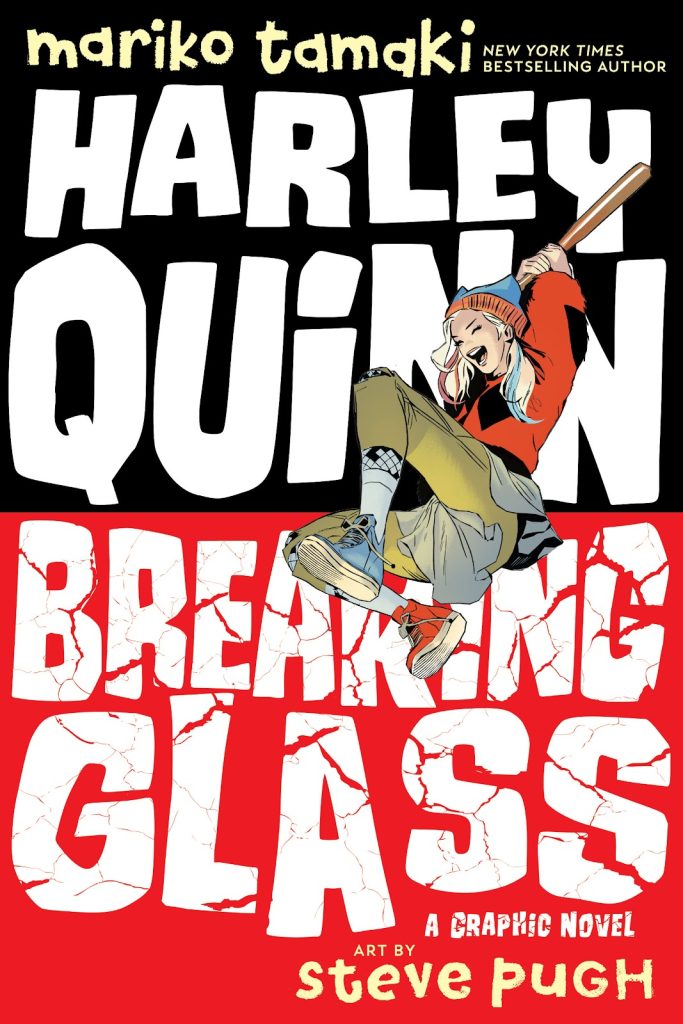

Breaking Glass is part of DC’s young adult reconfigurations of their characters, so don’t come here looking for the madcap antics of the Joker’s former sidekick trying to do right. If, however, your tastes run to a reconfigured fairy tale set in the modern day Gotham and exquisitely drawn by Steve Pugh, then come on in.

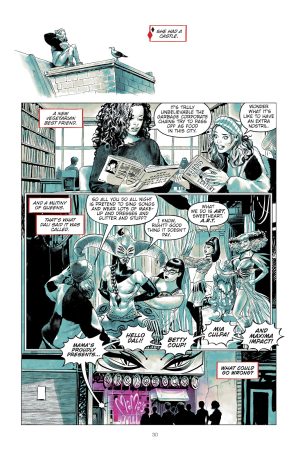

Harleen Quinzel is sent to live with her grandmother so she can attend Gotham High, but in between being sent and arriving her grandmother dies. It leaves Harley at sixteen with a Gotham apartment paid up for a few months, with her grandmother’s building manager happy with the arrangement as long as she keeps out of trouble. With Harley, of course, that’s easier said than done. Boundaries are largely lacking, and having fixated on Ivy at school because she’s interesting, the early stage of the friendship that develops is more a case of stalking. However, it’s a good move as Harleen is introduced to community activism and it solidifies her pre-existing belief in standing up for what you believe in.

Mariko Tamaki is top of the range when it comes to young adult graphic novels, and ensures planting DC’s most out there character in the middle of Gotham’s drag queens and a social agenda concerning smarmy developers is viable. Harleen becomes Harley far more naturally than in the mainstream DC universe, there’s a place for the Joker, and if Tamaki has the corporate villains of the piece a little too hands on, that’s okay as it makes them all the more hateful.

Pugh’s sample art is gorgeous, and represents the sheer beauty he serves up for page after page. His Gotham is almost Rockwellesque in its depiction, given a vibrancy and brightness not generally associated with the grimy and dangerous city. It’s virtually free of shadow. Visually, Harley creates herself from her surroundings, but Pugh’s Joker has a really fascinating visual reconfiguration.

Gotham being corrupt from top to bottom means justice is something you work out for yourself, a lesson Harley already learned back home in Putthole, and it makes the Joker’s form of direct action attractive. He’s also finding himself, but given there’s a limited cast, readers are likely to figure out who he is. That doesn’t matter, though, as it’s actions that count in Breaking Glass, and actions have consequences.

The final quarter isn’t what you’ll expect, and despite the shift in tone it’s equally compelling, and continues to underline injustice. There’s very much the feeling of unfinished business by the end, so a sequel is surely on the agenda.