Review by Bill Stone

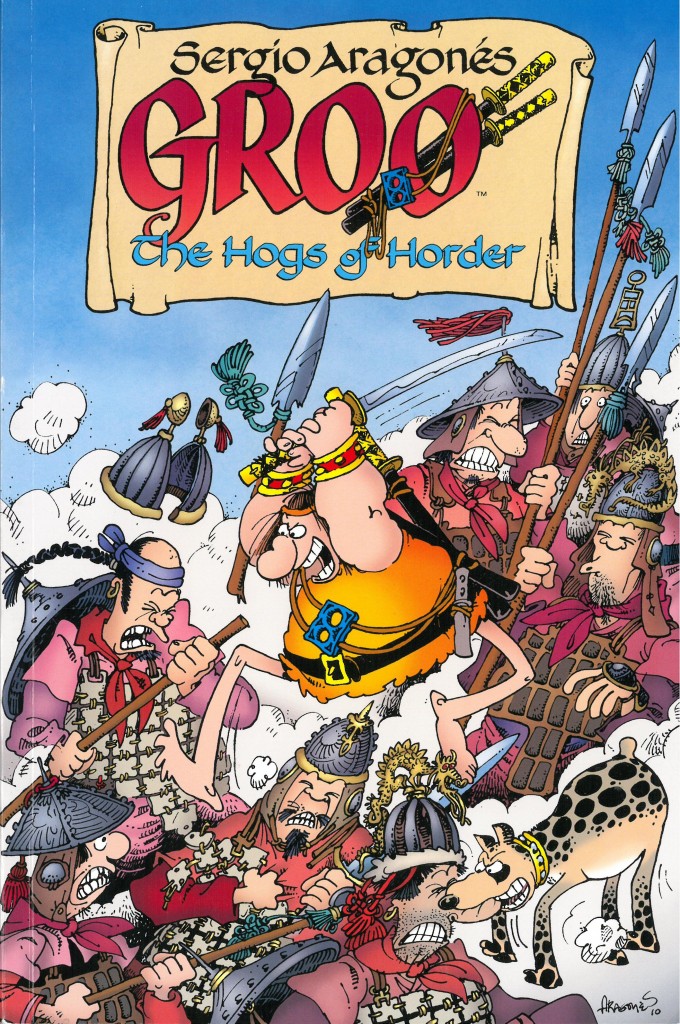

Groo is a naïf, possessed of two swords, an unquenchable appetite for the fray, a natural talent for destroying anything in his path, sinking ships without trying, a sizable misshapen nose and a wry companion in the form of a spotted dog. The dog is called Rufferto and provides a commentary throughout on the stupidity of Groo, war and the availability of food. He plays a role not a million miles from Gromit. Although with less cheese.

The story tells of the economic collapse brought upon the land of Horder, which when Groo pitches up is in the process of building and redevelopment. Through inadvertently trashing the new buildings, he causes the owners to throw themselves on the mercy of the banks. This also encourages artisans to source their products from neighbouring countries at fractions of the prevailing prices and thereby sets in train an economic collapse. That encompasses a run on the banks, a war deposing the king in a country who was put in place by the King of Horder, the failing of the carriage industry, smashing of glass manufacturing and the closure of the pottery industries.

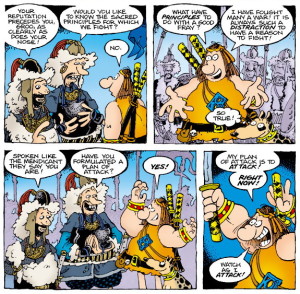

The story takes a dim view of economics, capitalism, military interventions, motivations of captains of industry and finally, in what appears to be an unrelated afterthought, the internet and social media. All of these scared cows are treated with the light and sensitive touch of a sledgehammer. The didactic nature is slightly leavened with a wry humour and a few good jokes, but it can’t escape the sum of its parts; it’s a quick, slight read.

Whilst it makes very good points, the polemic is undermined by the scattergun approach which has the effect of taking the edge off the injustices highlighted. It appears that if Sergio Aragonés had thought of other ills that blighted the world, they would also have been shoehorned in to the story. As it is, he includes a gag in about how cartoons and comics are an under-appreciated resource. The cartooning works beautifully however in reflecting the bemusement and confusion of the general populace to the economics of war.

This is damning with faint praise, despite a broad agreement with most of the points made. The gags work, as does the art, and yet it’s ultimately unsatisfying.

The package is rounded off with a series of Q&As about the authors, characters and travails associated with writing comics, four single page strips about a minor character and cover reproductions from the original floppy releases of Hogs of Horder.