Review by Colin Credle

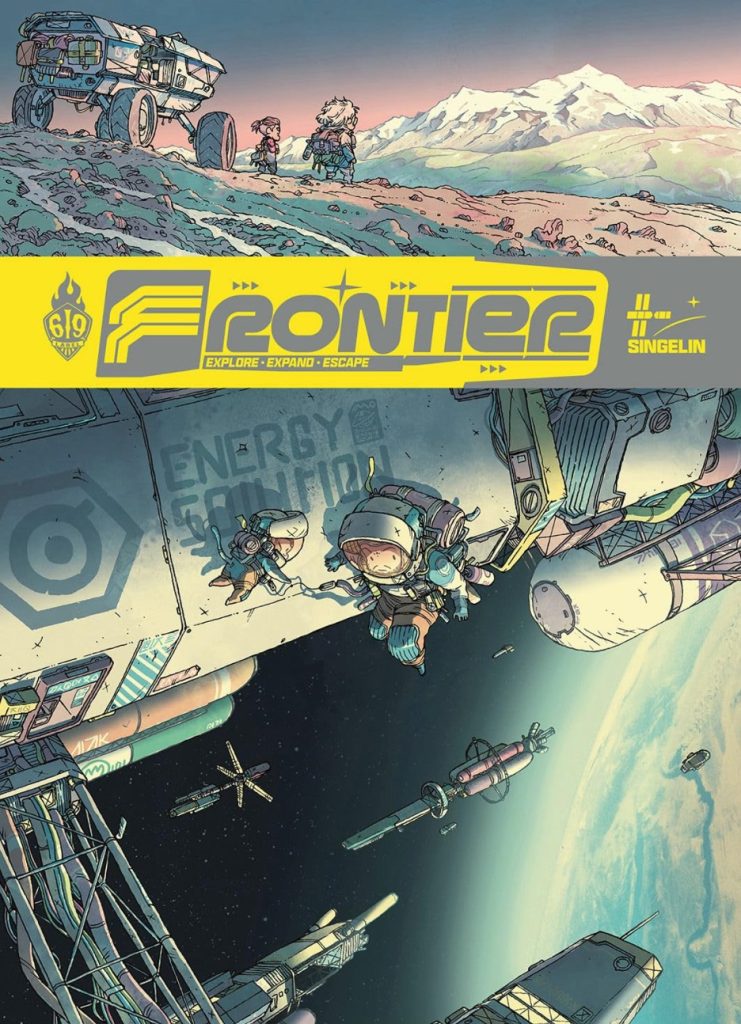

French Author and illustrator Guillaume Singelin released Frontier in 2023 to significant acclaim. It won the French Landerneau Prize for graphic novels as well as the Éco-Fuave Raja Award for best environmental, sustainability themed work at the Angouleme International Comics Festival. Following a well-trodden arc, we are presented with an empty husk of an Earth drained by the insatiable greed of humanity, forcing us into space exploration for survival and more mining.

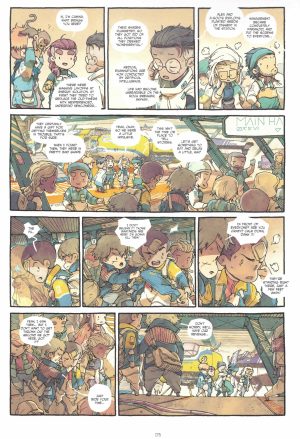

We follow three individuals. Ji-Soo is an idealistic research scientist who is overqualified and punished by the megacorporation for not toeing the line. Her constant whining reminds one of a sad-sack Eeyore – Pooh puts up with Eeyore with some affection, but Eeyore is still a bit of a drag with the chronic complaining. Camina is a no-nonsense former mercenary who after losing her arm in an industrial mining accident, pivots to make a living salvaging space trash. Lastly, we have Alex, a miner whose parents were born in space, which means he is known as a “spatial.” Alex is sentimental, passionate and often irrational with his sudden fits of self-righteous indignation. For added cuteness, Goku is a bar-coded chimpanzee who escapes the pharma labs to join our crew for laughs.

Singelin’s art style takes some getting used to, with bulbous heads, stunted legs and no noses resulting in caricatures that all seem to share the same body type. The cutesy factor juxtaposed with salty swearing, edgy violence and lethal action scenes can be amusing if not off-putting. Once well acquainted with our three heroes, we start to invest in their foibles. Unfortunately, instead of any real storyline, there’s a lot of sermonising on corporate hiring policies, on our greed exploiting resources at the expense of poorly paid workers, and corporate mercenaries shooting other corporate mercenaries on site. We even have scenes of workers in the cafeteria complaining about work policies.

Ji-Soo, Camina and Alex, though, are inspired by idealism. From divergent starting points, there is little surprise they end up together on a commune-like abandoned spaceship where everyone pitches in to the best of their ability and everyone gets along. History is replete with authentic examples why such experiments rarely end well, but to his credit, Singelin points out the commune’s nonviolence position will make it vulnerable to bulbous, noseless space pirates with short legs. Singelin’s depictions of exo-planets, spaceships and cramped living quarters are well crafted. Our stunted humans all fit nicely into the tight spaces left to them to navigate the consequences of our shared greed.

There is so much sermonising on our environmental sins and corporate employment policies that the pace lags, then atrophies into a slog until we finally reach a nice circular completion of our journey when Frontier is nicely tied into a bow. The end is a so much a continuation of the start, one wonders why we started in the first place.