Review by Ian Keogh

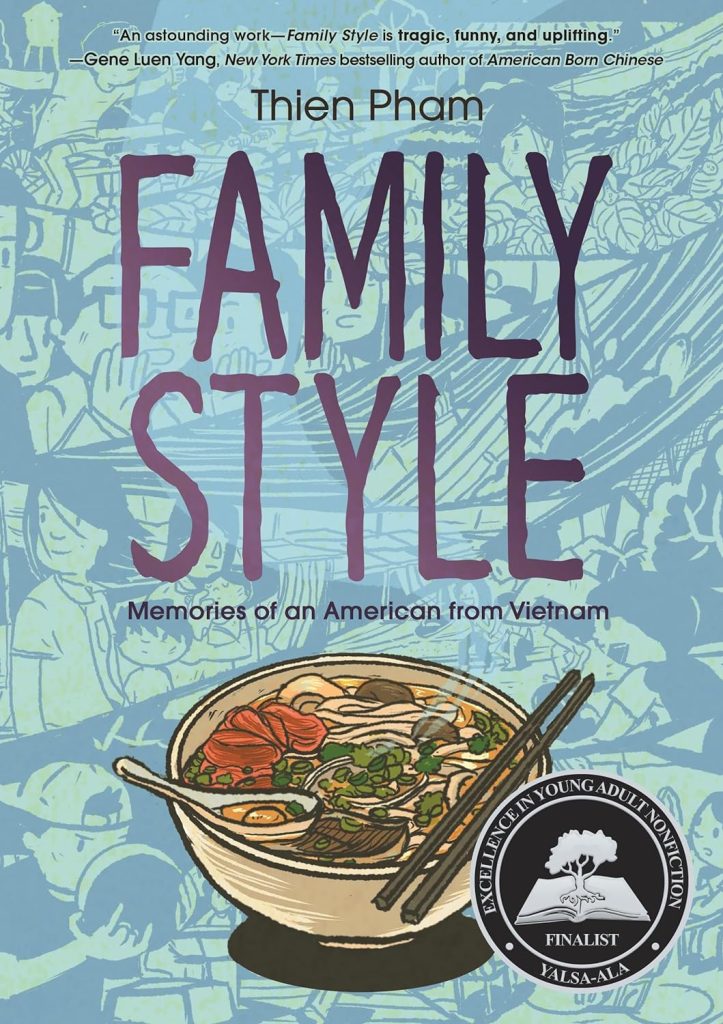

From the mid-1970s to the early 1990s hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese attempted to escape the repression and limitations of their regime by risking their lives in small boats on the South China seas, hoping to navigate to a friendlier nation. Among them as a young child was Thien Pham, and Family Style is his documentation of that experience and his life beyond.

Despite some grim experiences, Pham’s family were fortunate, both in surviving and in having a resourceful mother who could spot an opportunity. They survive in a refugee camp until selected for relocation in the USA from where Pham couples his own impressions as a child, with his parents’ experiences, much of which he was shielded from at the time. It’s instructive and heartwarming how the Vietnamese community support each other, letting people know if an apartment becomes available, who might share it to save costs, and spreading word of jobs that need plenty of people. It’s nevertheless one hell of a hard life. Would Americans under the same circumstances be as diligent or supportive? Pham employs the repeated metaphor of a magnet at specific moments, reinforcing the strengths of sticking together.

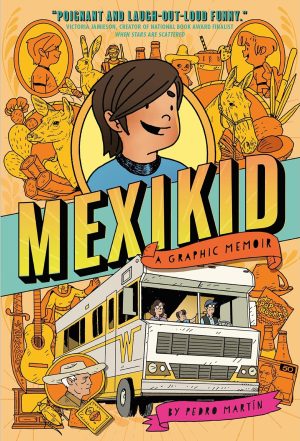

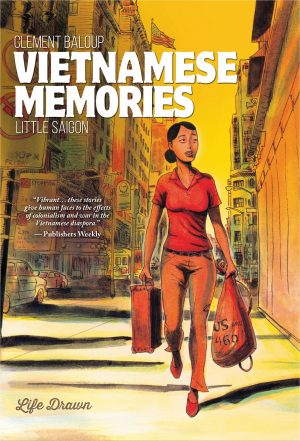

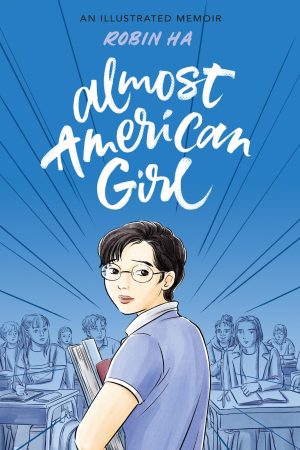

Several graphic novels relate the experiences of immigrant children who’ve arrived in the USA (see recommendations) and a pleasing aspect of Pham’s childhood in contrast to some others is that his teachers are caring and take time with him.

At the start it may take some settling into Pham’s storytelling, in which he uses form for effect. It’s apparent in the opening sequence when the small boat he’s in aged five is attacked by pirates. Pham relates the experiences punctuated by all-black spreads with just a single panel of dialogue with the panels of artwork on alternate pages closing ever further in on attackers. It’s clever, but the complexity of hope on a wing and a prayer in the face of reality may not transmit to the young adult audience associated with First Second’s output. With that sequence completed the pages become more conventional, although Pham does still occasionally try something different, such as the merger of reality and ideal in the sample art.

Pham takes a leap of several years for Family Style‘s final third. His family are now running a video rental store, and the stress that marked his earlier years has diminished, yet the purpose is to convey how little of his own culture remains for the teenage Pham. By the final chapter Pham is a teacher, yet he’s never bothered to become a US citizen, something he rectifies with a pernicious and narrow form of US nationalism ever more obvious in the early 21st century.

Endearingly, Pham anticipates questions that may arise, and produces extra short strips following the main story to answer them.

Family Style is uplifting without ever becoming too sentimental, and nor does it neglect massive problems, the likes of which most readers will never have to live through. Pham engages with subtlety and ensures truths prevail.