Review by Tony Keen

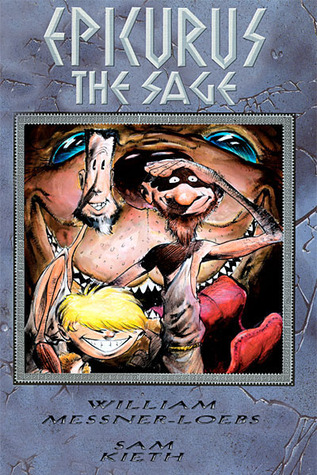

Bill Messner-Loebs and Sam Kieth’s Epicurus the Sage was a product of DC’s early creator-owned imprint Piranha Press, and first appeared in 1989. A second volume turned up in 1991. This 2003 collection brings together both stories, as well as a black-and white piece that first saw print in Piranha’s anthology comic Fast Forward, and a new tale that would presumably have been the third volume of the Piranha series. Sadly, Piranha was wound up in 1994, and, convolutedly, this collection appeared from Cliffhanger!, an imprint of WildStorm, which by 2003 was owned by DC.

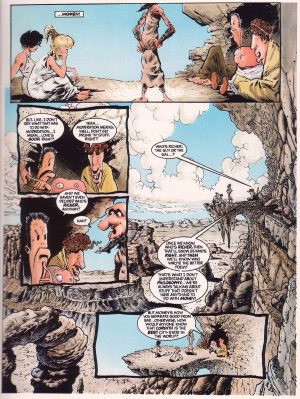

Epicurus is a cheerfully anachronistic mix of Greek history, mythology, and slapstick. The titular sage is a Greek philosopher, who really lived in the last fourth century BCE. Here he is accompanied by another philosopher, Plato (in reality dead a few years before Epicurus was born), and the young Alexander the Great (who historically died when Epicurus was fourteen). The three find themselves involved in some of the chief Greek myths. In ‘Visiting Hades’, after a lot of scene-setting, Epicurus has to find Persephone, the daughter of the harvest-goddess Demeter – Persephone has eloped with Hades, the god of the Underworld. In ‘The Many Loves of Zeus’, the trio encounter many of the women that Zeus seduces or rapes through the tales of mythology.

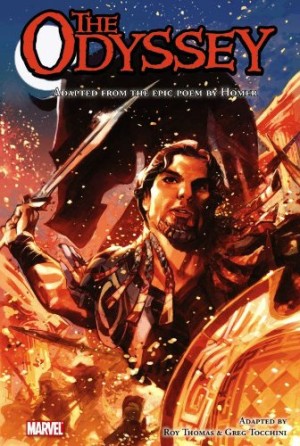

‘Riding the Sun’, from which Alexander is absent, mixes the stories of Phaethon, the son of Apollo who rode the chariot of his father, leading the sun, and Cassandra, the Trojan princess gifted with prophecy by the same god, but cursed never to be believed. It is most notable for Messner-Loebs’ inclusion (anachronistically, of course) of the epic poet Homer, whose presence allows Messner-Loebs to start to comment on the relationship of story to events, and how what’s written down doesn’t necessarily resemble what actually happened.

This distinction between the truth and the stories that are told is played up in the new story, ‘Helen’s Boys’. Here, Messner-Loebs and Kieth tackle the big one – the story of the Trojan War. A number of other myths are thrown in, and it is all treated with the irreverence that the reader has by now come to expect from Epicurus.

Epicurus is clearly a labour of love for both creators, and that leaves it open to accusations of being the an indulgence that could only be created by someone who really didn’t care about their audience at all. Certainly, a reader fully familiar with Greek history and mythology will get more out of Epicurus than one who is not, but there is enough slapstick to amuse everyone, and most of the other jokes don’t need too much work on the part of the reader.

Then there is Kieth’s artwork. It is always highly stylized, tending towards cartooning and exaggerated caricature (see sample image). By ‘Helen’s Boys’ he is producing figures that look more and more grotesque, and stepping further and further away from anatomical realism. This, it is fair to say, is not to everyone’s taste.

Nevertheless, it has to be said that the people who do like Epicurus like it very much. Whilst nothing ever quite matches the invention of the first story, there remain delights throughout the collection, and the strip is probably best experienced in this collection.