Review by Ian Keogh

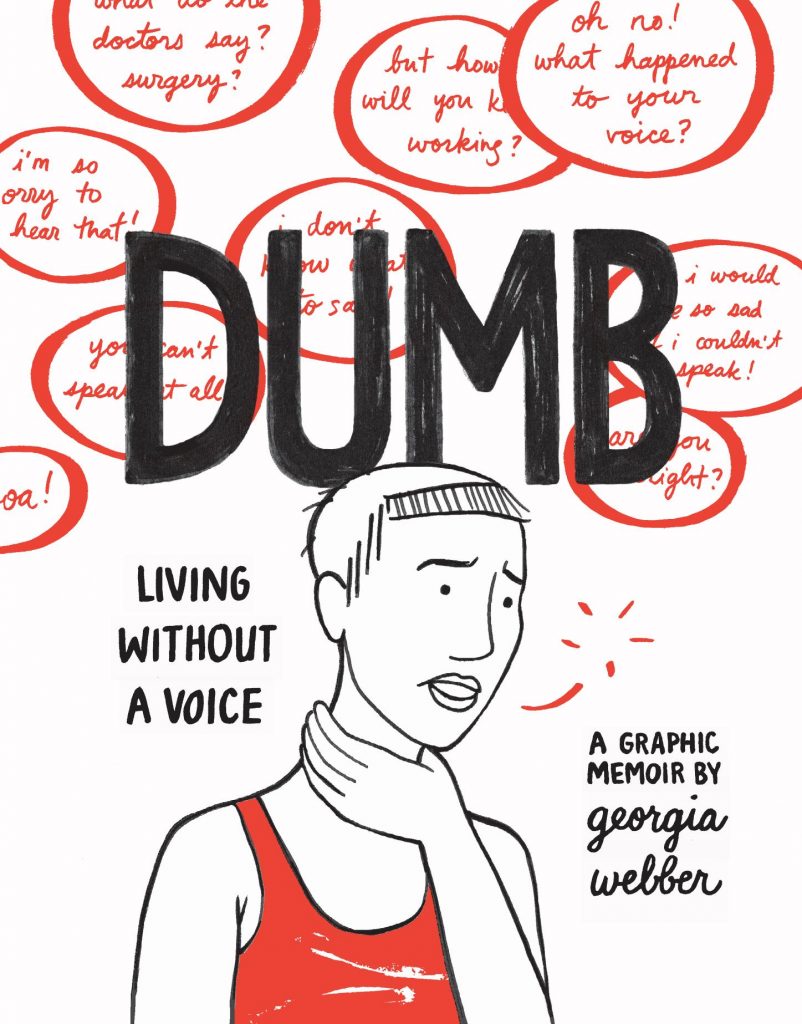

It takes Georgia Webber five months to see a doctor after she begins experiencing trouble with her voice. After a check for more serious illness, on the basis of admitting she’ll occasionally sing, Webber is labelled a “voice abuser” by the doctor, told to rest a lot, take lots of fluids and come back in six months. It doesn’t need any accompanying illustration to convey how dispiriting this cursory diagnosis must have been. If that wasn’t bad enough, the system is set to grind down anyone unable to talk. Webber has to quit her job, and rapidly discovers the impossibility of finding an alternative where speech isn’t expected.

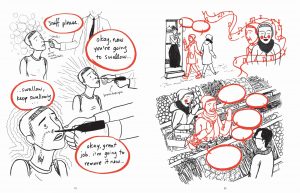

What the first half of Dumb conveys is how much we take speech for granted. When robbed of being able to communicate by speaking, Webber loses friends some of whom think her rude, and finds there is no convenient alternative. There are coping strategies such as carrying a whiteboard, texting people she’s standing next to, and having to devise other methods of communication led her back to comics. She has a minimalist style, but only a basic technique, yet the topic transcends that to some degree, and she introduces an innovation used to separate her status from the ideal circumstances. Standard black and white conveys the reality while illustrations with red outlines are Webber simultaneously stepping outside her skin to present what she would normally be experiencing. In particularly frustrating situations this devolves into almost primal enraged red scribbles covering the pages.

Many of those frustrating circumstances involve Webber working her way through the welfare system in Quebec. As anywhere else, it’s characterised by labyrinthine processes, administrative incompetence, and constant repetition, reinforcing suspicions of a system no longer helping those in need, but channelled to discourage anyone benefiting from the public purse. From there we also have a discussion about spoken communication in the primarily French speaking city of Montreal.

There is help available, and by the end of the book Webber has accessed it. One of the pieces of advice is to share her experiences to help others, which is how Dumb came about. It’s not intended as a joke in poor taste to note that Webber takes a fair amount of time to convey her ideas. The making of points is extended, and the repetition of ugly looking pages expressing frustration don’t make this a reader-friendly experience. It’s possibly intentional, conveying the constant communication difficulties, but the result is off-putting as well as immediate, which is a pity as Webber has something to say and it should be heard.