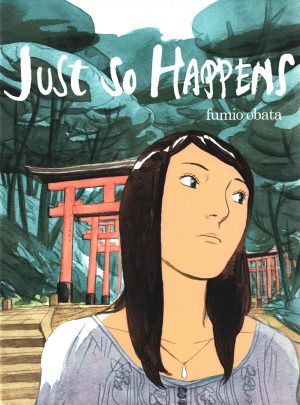

Review by Ian Keogh

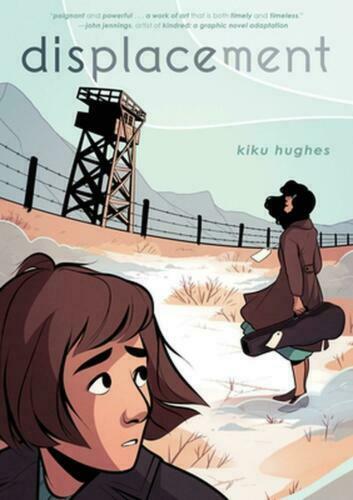

It’s a strange choice to give your lead character your own name, but it’s safe to assume Kiku Hughes doesn’t experience periods where she’s shifted through time and into another location. However, it’s the narrative method she uses to explore her family’s history as Japanese Americans within the context of Donald Trump’s presidential proclamations and his narrow view of what constitutes an American.

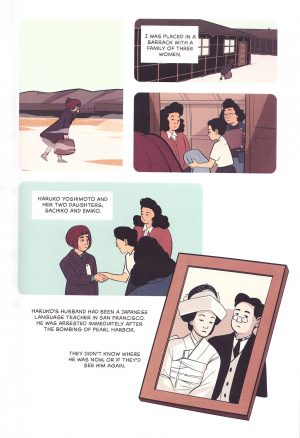

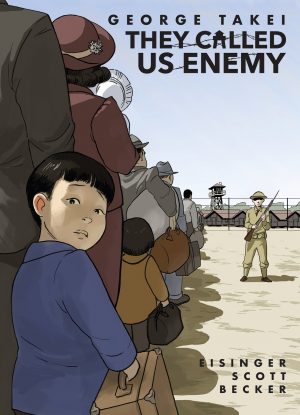

As time passes fewer and fewer people remain aware that one US response to the Pearl Harbour attack in 1941 was to imprison over a hundred thousand of its own citizens. Anyone who was even one sixteenth Japanese (ie had one Japanese great, great grandparent) was allocated a number and shipped to what’s been historically referred to as an internment camp, although some now consider that term diminishes what was a concentration camp. Whatever the term, the vast majority of those kept captive considered themselves American. Hughes can trace this treatment back two generations to her grandmother Ernestina, and via the method of time slippage shares her experiences. This is because while her initial displacements were brief, the third is prolonged. It’s a clever device that offers no easy escape, so the 21st century Kiku who speaks no Japanese is trapped alongside the people of the 1940s.

The title refers to both the method of slipping back through time and what happened to the Japanese Americans in the 1940s. Hughes keeps the art simple, because this isn’t a simple topic, and it’s easier understood without distractions, yet the mixture of thin line and muted colour is very easy on the eye.

To consider any such vast number of people as a single group is an error, and while heritage united them, opinions on politics and social policies were greatly varied, and even among themselves Japanese Americans applied categories referring to the number of naturalised generations. A key issue is a loyalty document, the phrasing of which implies that anyone agreeing with a particular clause had previously been loyal to the Japanese emperor, yet disagreeing meant immediate transportation to a more secure camp. Presumably Hughes mixes her grandmother’s recollections with historical research to provide a full picture, and while in the past the little knowledge she has of events is of almost no value. The one big advantage she has is knowing that however unjust, most people survived the experience, which isn’t something she’s able to share with a community frightened that the guards’ guns could be turned on them. Her greatest concern becomes that she’ll be stuck in the past, living out a life seventy years before her time.

There is a solution, and over the final chapters we catch up on Ernestina’s post-camp life amid a creatively charming mother/daughter bonding moment. It leads into Hughes detailing how researching the family history activated her own sense of social justice in that regard.

Almost everything about Displacement works. However, having leaned heavily on a fictionalised aspect, it’s surely a duty to let readers know how other people fared after the camps. Even just an illustration with a catch-up paragraph below would do, but as it is we’re bereft. The unfinished business is a minor point, but important. Otherwise the personalised approach to history is painlessly educational, the modern day contextualisation is smart and essential, and Hughes makes sure we understand conflicting views. It’s a compelling read.