Review by Frank Plowright

Don’t be put off by the awkward title. Marc Malès produced a complex, yet primarily dispassionate, examination of both emotional despondency and human reaction to physical beauty. It’s set in the past either to distance or to underline the issues as ones perpetually with us. There are occasional moments when Jonathan Tanner’s translation is too literal, and therefore awkward, but for the most part he’s excellent in delivering the English version of a sparse, but emotionally multi-faceted story.

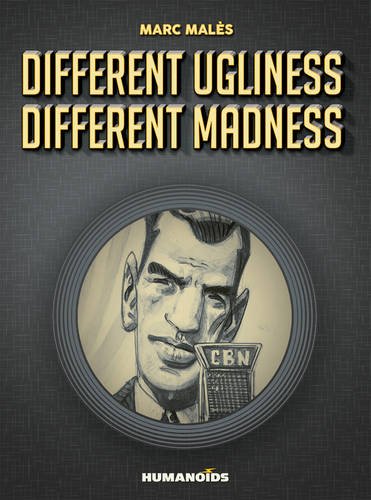

In the 1930s Lloyd Goodman is a national celebrity across the USA. In an era before television his smooth baritone seduces millions via radio, epitomising a glamorous high life that offers a brief daily respite from the hardships of depression-era poverty. His handsome face smiles from posters all over the country and his public appearances draw large crowds. That, however, is all manufactured.

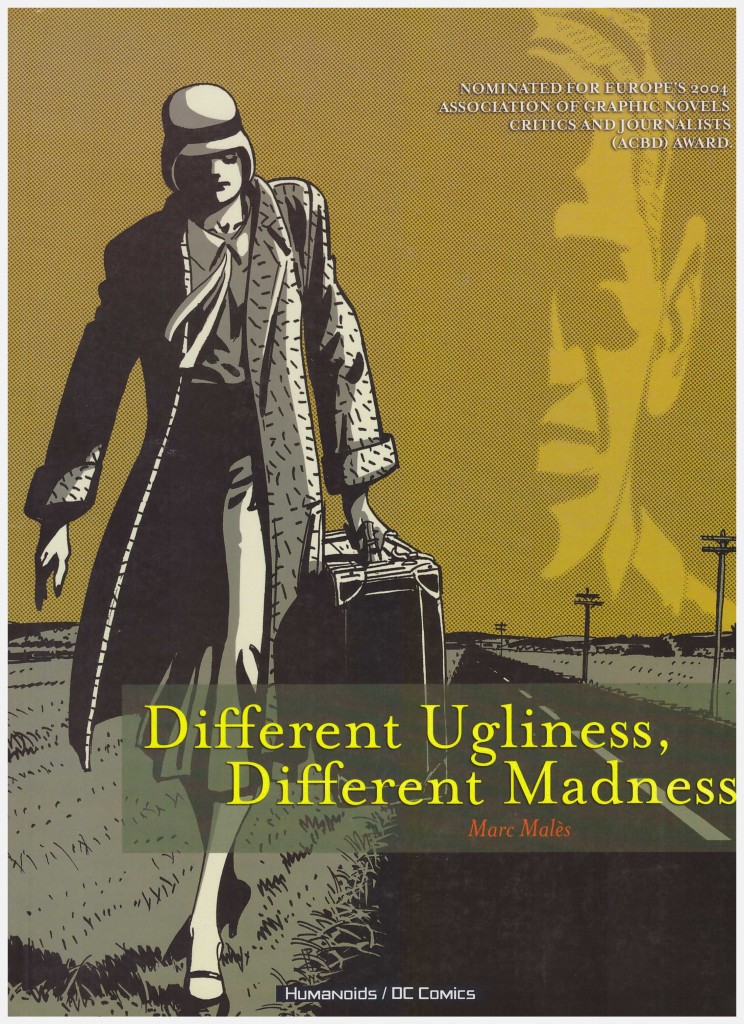

It’s Helen with whom the story begins, a stunningly beautiful woman traveling a seemingly random course across the nation that ultimately delivers her to a remote rural area. As with Goodman, her alluring appearance hides secrets. She’s mentally scarred by the recent death of her twin sister, with whom she converses via mirrors and other reflective surfaces. Chance leads to her meeting the taciturn owner of an isolated property, and she accepts his invitation to remain there with no strings attached. Far from conventionally handsome, and seemingly based by Malès on 1950s actor Rondo Hatton, he’s a difficult individual with his own ghosts, and the pair gradually shed their troubles enough to restore themselves to the outer world.

The scenes from the 1930s are parsed with some from the 1970s, suggesting that some ghosts are never laid to rest despite all appearances to the contrary.

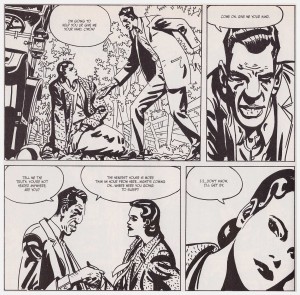

Malès‘ starkly contrasted black and white art reflects the bleakness of his story. He’s deliberately not polished the rough edges, and there’s extensive use of deep black shading to indicate mood. This isn’t cheerful or reassuring material, but it is a fascinating exploration of how we can contrive to hinder full participation in life, and how social pressure is complicit.