Review by Frank Plowright

Cartoonist Brick (John Stuart Clark to his parents) has a career stretching back to the late 1970s, but this is his first graphic novel. As the title indicates, it deals with his depression, which for him manifests first as testicular pain, before progressing to a hallucinogenic state where Brick is conversing with himself as a large white lizard.

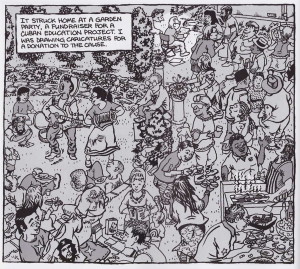

The spartan and glum cover may reflect the topic, but it’s rather at odds with the interior content. Brick’s background in single panel cartoon statements is very apparent to begin with, as there’s little panel to panel continuity. Instead we have a read that’s denser than usual as he attempts to pack a visual or verbal gag into almost every panel. When he opens up into crowded half page scenes it brings to mind the European style cartoon storytelling of Morris or Uderzo, with almost impossibly busy pictures. Depresso, though, is a learning process and as it continues it expands artistically as Brick finds ways to illustrate his experience and his vivid nightmares.

The book also opens out narratively. An extended interlude in China, for instance, seems for some while better suited to a separate travelogue, but Brick eventually pulls this together with a discourse on how the Chinese approach depression. It’s astonishing to learn that it wasn’t officially recognised as a condition until very recently.

Brick narrates as a self-caricature from the start, but the manner in which he inflates his repertoire and approach creates a veritable scrapbook in the manner of Bryan Talbot’s Alice in Sunderland. We have a capable Peanuts pastiche, photographs, detours into the treatment of mental illness through the ages and assorted imaginative methods of conveying the almost impossible. Not all the cartooning, though, is first rate. The caricatures would be unrecognisable without associated reference, and at times the book would benefit from easing the pace in preference to constantly shoehorning in gags or exaggeration. Yet this is such a personal undertaking, that it’s possibly the only way in which Depresso could have been completed.

The entirety gradually builds into a grim picture of mental health treatment in 21st century Britain, one where the chemical cocktail with only a slim chance of working is the first and largely sole resort. Problems that aren’t visible, are considered negligible, and Brick’s honest enough to concede this had been his attitude in the past. Support services are few, and being referred to a therapist can take years.

Not everything detailed is Brick’s own experience, the reason for using the possibly allegorical identity of Tom Freeman, but he approaches Joe Matt levels of unsavoury self-revelation as an essential facet of building an honest narrative. By the book’s end we’ve been treated to a comprehensive analysis of depression, the various forms of treatment, and Brick himself.

Given the prevailing lack of understanding about depression, Depresso is a book that may be useful to many people as well as entertaining, if only to show there can be light at the end of the tunnel. Job well done.