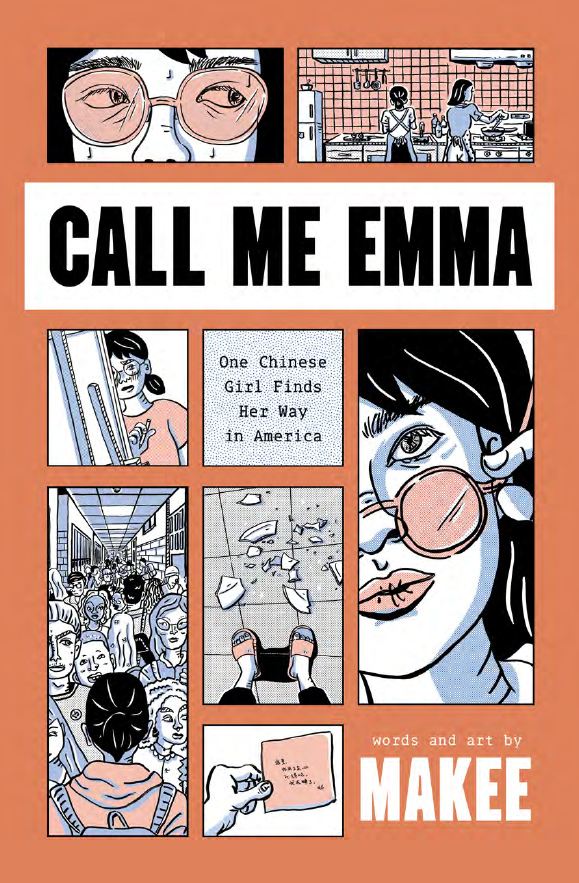

Review by Ian Keogh

Makee has been told her whole life her family are going to live in the USA, but she’s sixteen before the necessary visa procedures have been finalised. Her mother’s sister has already raised a family there, and advises learning to speak English well, rather than the version supplied in Chinese schools intended for passing written tests, not speaking. Hearing the mangling when her name Yi-xuan Liu is spoken, she rapidly learns there’s no meeting halfway, and settles on Emma as a name, based on actress Emma Watson whom she knows from the Harry Potter movies.

Seeing your own country through the eyes of newcomers is a way of considering how what’s taken for granted through familiarity can seem extremely unusual to others, as per the daily recital of the Pledge of Allegiance in schools (sample art). In common with many other newcomers to the USA Emma also notes how selective Hollywood is in their portrayals of ‘reality’, and that there’s no respect for the professions of immigrants. Her father was a college professor in China, yet works as a New York tour guide, and her mother in a nursing home having been an office clerk, and that brings its own pressures, ones that Emma only understands in hindsight.

While struggling with the nuances of American high school and society in general, she’s also able to see aspects of American life that improve on what she’s been used to, not least a society that values people for more than their school grades, which is the case in China. Much of Call Me Emma is a two way consideration of national circumstances, and how that shapes Emma’s view of the world. She’s used to studying hard, and can’t understand classmates who idle their time away not learning. More controversial are attitudes Emma hears about African Americans. What she’s taught in China is plain racist, and it’s reinforced in the USA when people judge an entire section of the population based on their experience with one of them, but Emma is researches to make up her own mind.

Much is made in school sequences of Emma being a talented artist, which is apparent in the composition of panels, the neatness applied to scenery when it features and the way people are differentiated, but the style isn’t appealing. It’s sketchy and too rarely features backgrounds, also drawn well.

Emma adjusting to her new life is the priority for half the book, but while she does so, other members of the family aren’t coping, and their experiences feature for the remainder. It’s punctuated, though, with sequences seeming to have little meaning other than acting as a memoir, such as several pages recalling a Thanksgiving dinner. These scenes dilute the more interesting personal and family experiences, while there’s also a feeling of glossing over one set of circumstances, which may be for the sake of privacy.

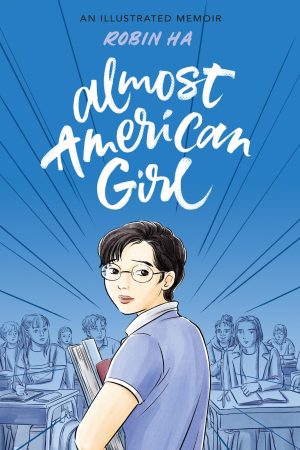

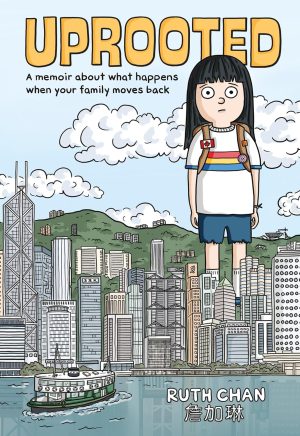

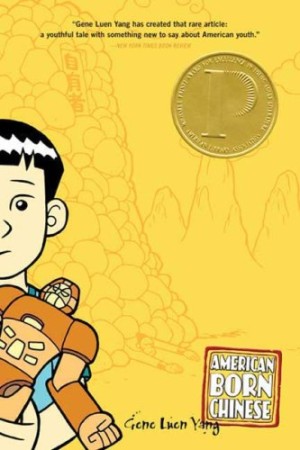

As Emma leaves school she reverts to her real name, so there’s no explanation of the Makee alias used for creating Call Me Emma. Other autobiographical graphic novels deal with Chinese immigrants to the USA, but individual experiences make the difference. Where Makee succeeds is in explaining cultural differences, and with the understated presentation of revelatory scenes such as a conversation with her mother toward the end, but this is frustrating graphic novel for all too often diverting away from what’s interesting.