Review by Frank Plowright

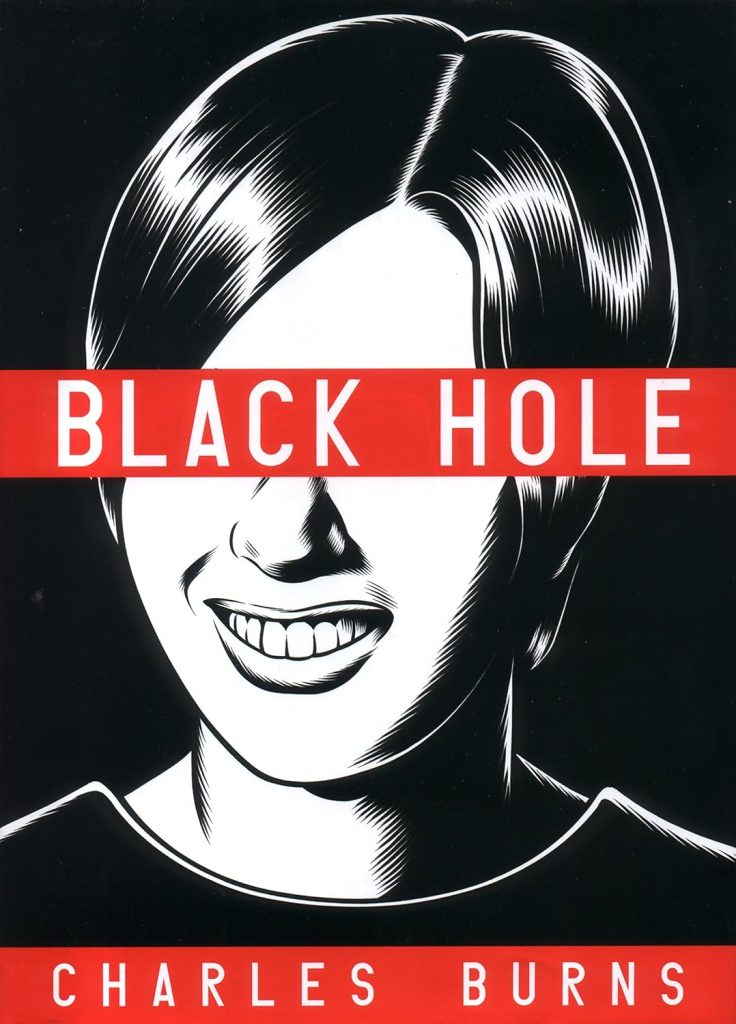

Concerning teenage sexual exploration leading to deformities, Black Hole is the graphic novel that cemented the reputation of Charles Burns, transforming from him from a purveyor of well crafted oddities to someone capable of a sustained narrative. It remains a lynchpin of his back catalogue belying the troubled decade-long path to completion when originally serialised from 1994, gradually becoming more confident chapter by chapter.

Keith is first seen among his jock peers in an alternate pre-punk 1970s, but he’s been having disturbing dreams. Chris has had a disturbing encounter, and it’s left her literally scarred, something her peer group realise before she does. As the deformities are transmitted by sex, at first they seem an obvious metaphor for AIDS, but Burns runs that deeper as it’s not a singular condition, but one with multiple manifestations, different for each victim. A sexual undercurrent is represented by an abundance of both vaginal and phallic symbolism, and there’s a carefully cultivated sense of unease throughout. It’s partially via the unknown effects of sexual transmission, and later via a more physical threat.

As Burns becomes more confident he switches from short chapters to longer, more structured episodes featuring a broader cast. His depiction of teenage uncertainty, desire and experimentation is unsettling, and occasionally via the cast’s drug use Burns is able to heighten their insecurities. He builds a world where we come to realise even the seemingly confident are stumbling in the dark, and renders it even more disorienting via constantly using flashbacks as a story device while also touching on teenage depression.

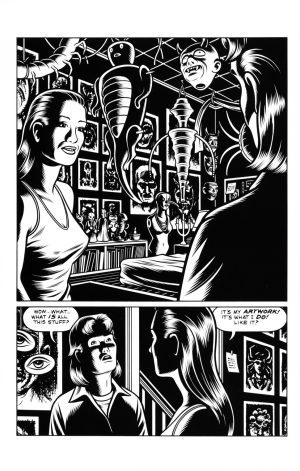

To that point in his career Burns had never needed to define a broad cast over a sustained page count, yet everyone here is recognisable throughout, even Keith with shorter hair. Extending a virtuoso series of definitions, opening endpapers feature portraits of students as if in a high school yearbook, while closing endpapers show them transformed. His already familiar high contrast flat black and white art serves well, the darkness of the surroundings reflecting the dark mood of the narrative thoughts and the moth to a flame cravings.

An air of increasing doom is sustained by Keith’s frightening dreams punctuating Black Hole, and as events deteriorate and the clever title takes on a second meaning readers will be left wondering how many of the cast will get out alive.

Burns is an instantly recognisable creator following a path that’s resulted in many admirers, but no obvious imitators. Perhaps it’s because anyone trying discovers just how time consuming the precision of his rendering is. The fusion of horror and social anxieties still transmits strongly, some themes of alienation universal even if a period piece when first published.

For those concerned more with the art than a leisurely story, Fantagraphics have issued a lavish oversized edition reproducing the pages as if Burns’ original art, but this doesn’t feature the entire story.