Review by Frank Plowright

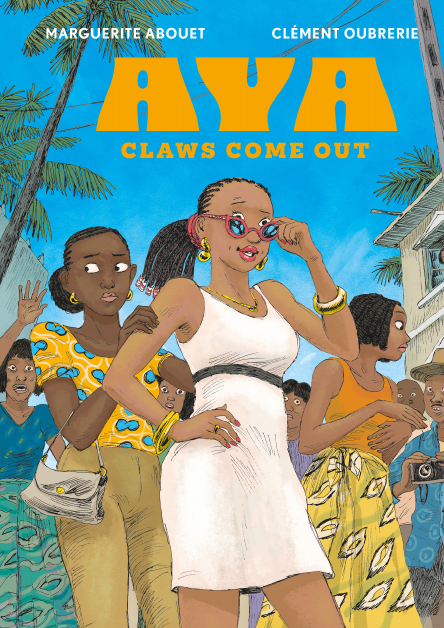

Life occasionally throws up a delightful surprise, and such is the case with The Claws Come Out. Marguerite Abouet and Clément Oubrerie’s last look at Aya and her Ivorian neighbourhood of Yop City was published in 2010, so what were the odds on the series being revived again in 2022?

Her last outing was only available in English as part of the three volume compilation Life in Yop City, but a two page introduction of the cast should bring everyone up to date on their broader lives in 1981. Aya is hoping to continue her studies and to avoid Didier who’s infatuated with her, Bintou has become the star of a TV soap, and Adouja is concerned about the disappearance of her brother Albert, who revealed to his parents that he’s gay. Rather than accept the truth they prefer to believe people in the village have bewitched him. Also gay, Innocent has decamped to France, but is danger of being deported unless he can obtain a residency visa. His name is no coincidence, and while used to spotlight the struggles of people from places formerly occupied by France to stay in Paris, his blend of naivety and selfishness supplies many funny moments contrasting earnest political activists.

Abouet has always been a masterful storyteller. She combines slice of life drama starring believable people with finely dropped comedy moments and some social commentary. So smoothly does The Claws Come Out pick up with the cast it’s as if there’s been no absence. As ever, Aya is the fountain of common sense among the assorted flights of fancy those in her vicinity have. She negotiates a world where it’s who you know, not your capabilities that earn prestige and progress, and where superstition sometimes outranks reality.

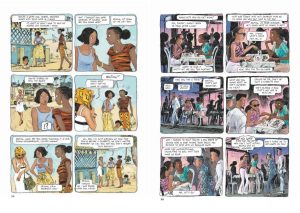

The cast are brought to even more vivid life by Oubrerie, whose visual delicacy is loose, yet extremely expressive, and a strength is ensuring readers know how the cast are feeling, even if they’re trying to conceal it. It’s also noticeable how well defined the locations are, the streets meticulously constructed, yet with touches displaying these aren’t hollow shells, but places where people live.

As before, what passes for acceptable behaviour on the part of men in 1980s Abidjan is outrageous, as seen on the sample art. That’s part of a running plot about people being unable to differentiate Bintou the actress from the home-wrecking soap opera role she plays on TV. From a writer who didn’t grow up in the community she’s writing about it might seem patronising at best, but Abouet has noted loosely basing the cast on people she knows. She skilfully starts extremely readable plots that escalate into serious situations, and more so than the earlier volumes, The Claws Come Out ends on not just one cliffhanger, but with four people in varying degrees of danger. Thankfully, then, a continuation has recently been published in France, and will presumably follow from Drawn and Quarterly in due course.