Review by Graham Johnstone

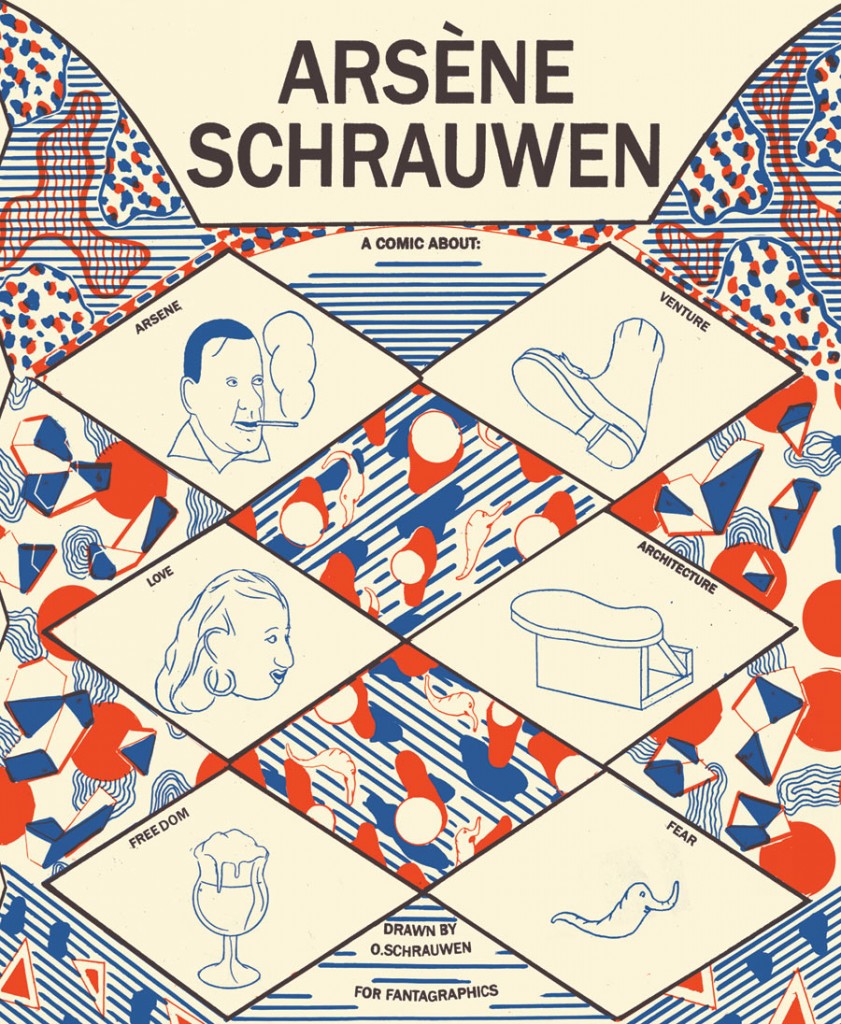

Olivier Schrauwen’s ‘Congo Chromo’, collected in The Man Who Grew His Beard, captured both the innocence and brutality of the colonial world. It looks now like a prelude to Arsène Schrauwen the supposed memoirs of Olivier’s grandfather.

After the Second World War, Arsène responds to an invitation from his cousin Roger to join him in the colonies, and help realise his vision of a model city. While actually inspired by fragments of his grandfather’s experience it’s not a realistic memoir, and more a journey of the imagination. It’s Olivier’s attempts to convey Arsène’s perception. For example, in an early scene where a departing Arsène “watches Marieke’s silhouette shrink” he draws a large line silhouette, containing like Russian Dolls a smaller one and an even smaller one.

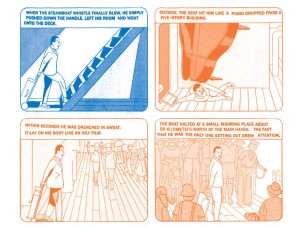

Olivier’s artwork has a cultivated naive look, with fine hesitant lines and pale ghosted backgrounds. This captures Arsène’s limited grasp of his new environment. Unknown details like the faces of minor characters are almost blank – at least until they become more significant in the story.

Behind this though is a smart artist who understands comics and makes witty play with the form. For example to show Roger’s wife Marieke swimming, the panels follow her round in a loop. It’s playful fun for the reader, but also lets us experience Arsène’s fascination with this voluptuous woman – we’re caught in the loop with him.

In a later two-page spread he’s walking aimlessly and we’re not sure quite which way to read the panels or captions. We start reading in the traditional left to right, then there’s a panel where he walks the opposite way, or a panel floating out in space… Behind all the panels, there’s a ghost image of Roger’s ‘palace’, and he’s roughly following it’s paths and stairs and archways. “Every step he took was resolute, yet completely random”. Schrauwen messes entertainingly with our expectations of how comics are read, and conveys the sense of Arsène’s aimless yet anxious walking.

It’s printed in two colours, orange and blue, with most panels being entirely one or other. It’s not just a gimmick, but cleverly supports the narrative, for example changing to denote hot and cool places. There’s a page to indicate he sleeps for a night: it’s almost blank, but with a pale blue on the left fading into an almost invisible pale orange on the right. The page number is blue on the left and orange on the right.

Fears of this unknown country focus on ‘elephant worm’ thought to be present in any water and able to invade any opening in the body with hideous consequences. This keeps him in his sweltering cabin during the rainy season. We see a two-page spread cutaway shot of the cabin with eleven of Arsène in his underpants, sitting drinking, pacing, sitting drinking, pacing, always sweating. It’s packed with captions of his racing, repetitive thoughts that follow the round roof of the hut circling back on themselves. When he eventually escapes the claustrophobic cabin we feel his bold elation.

When Roger’s manic energy takes him a step too far, Arsène finds himself the reluctant figurehead of the project. “The machinery of ‘Project Freedom Town’ had been set in motion, and there was no way to slow or halt this titanic undertaking now.”

This is both a real human story and a feat of joyous creative imagination. Each of it’s 250 pages feels like a fresh delight. Even in the increasingly busy landscape of graphic novels, there’s almost nothing to begin compare it to. It won the 2015 Society of Illustrators annual competition for Comic and Cartoon Art.