Review by Ian Keogh

Spoilers in review

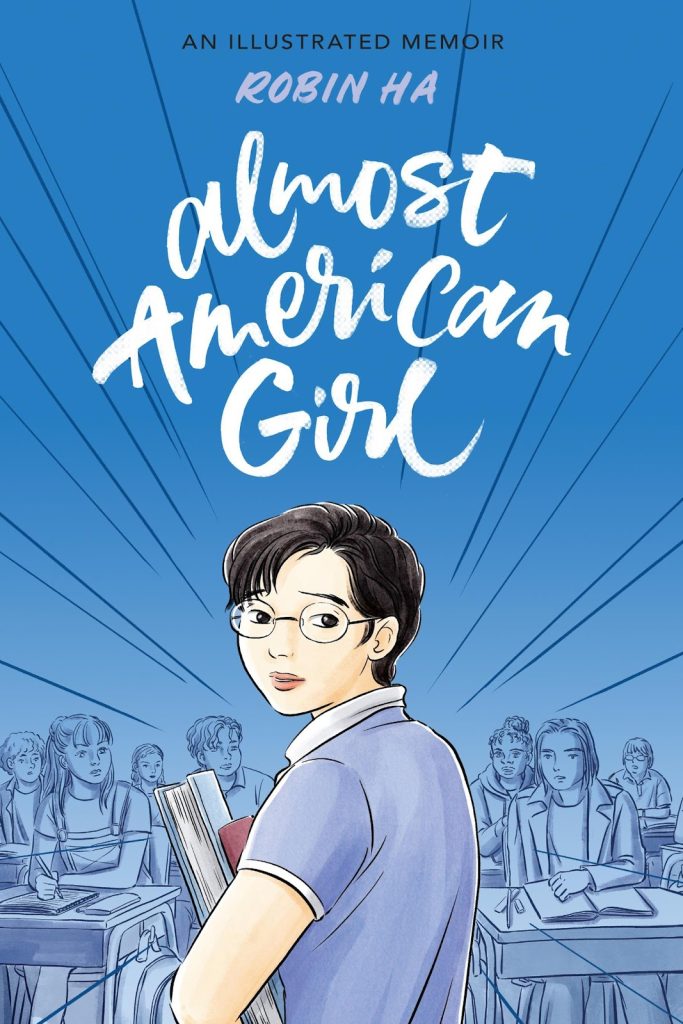

When she was fourteen in 1995 Robin Ha’s mother announced they were taking a holiday in the USA. What wasn’t mentioned is their meeting a Mr. Kim there, that her mother intends to marry him, and it’s not a holiday, but a move and their new home is in Alabama.

It’s a while into Almost American Girl before Ha reveals most of the above information, but it’s so integral that it’s impossible to review the remainder without mentioning it. Ha notes believing her mother always has her best interests at heart, but this isn’t the only example of extremely callous behaviour. It leaves Robin in a new country attending a new school, yet only having a passing knowledge of English. Worse still, the new name she’s chosen is difficult to pronounce in English as Korean language lacks an ‘r’ sound. Her new stepsisters and step-cousins aren’t greatly sociable, and their reticence increases in school, where racial bullying starts immediately. Heartbreakingly, this isn’t the first time for school difficulties, as the rigidity of Korean society meant Ha was considered trashy for coming from a single parent family.

Navigating high school is difficult enough for children born in America, but the lack of support Robin is offered to acclimatise is a damning indictment of Alabama’s school system. Never mind pupils, as related here there’s little acknowledgement of Robin’s problems from staff, although a single understanding teacher is the exception. Ha delivers this all as matter of fact, but the simple art could do with greater feeling in places, although there’s evocative use of colour during a couple of moments of extreme emotional stress. However, lack of strong emotion is the weakest part of otherwise appealingly rendered watercolour art. Ha stresses how important comics were to her from a young age, and drawing provides momentary comfort amid turmoil even before they prompt a major social breakthrough.

Cultural differences come up in passing as Robin adjusts to her new life, and what’s new, strange and accepted makes for instructional reading. Her mother, though has the single answer to any problem, and being exhorted to try harder isn’t helpful with Robin’s less assertive personality. The relationship between mother and daughter is well presented as fundamentally loving on both sides, but difficult, with a surprising lack of understanding on her mother’s part that the afterword reveals extends to the present day. It supplies simmering tension as Ha feeds family history into the ongoing events of 1995 and 1996, along with practices considered normal in Korea, but shocking in the USA, like bribing teachers. The cultural criticisms aren’t caustically delivered, just mentioned in passing.

While not without early bumps, Ha’s American life turned out okay, and she flourishes in a more cosmopolitan environment. There’s a feeling though, that plenty of children, not necessarily just from Korea, are experiencing similar cultural shock today and in Robin they’ll find a sympathetic ear and shining example.