Review by Frank Plowright

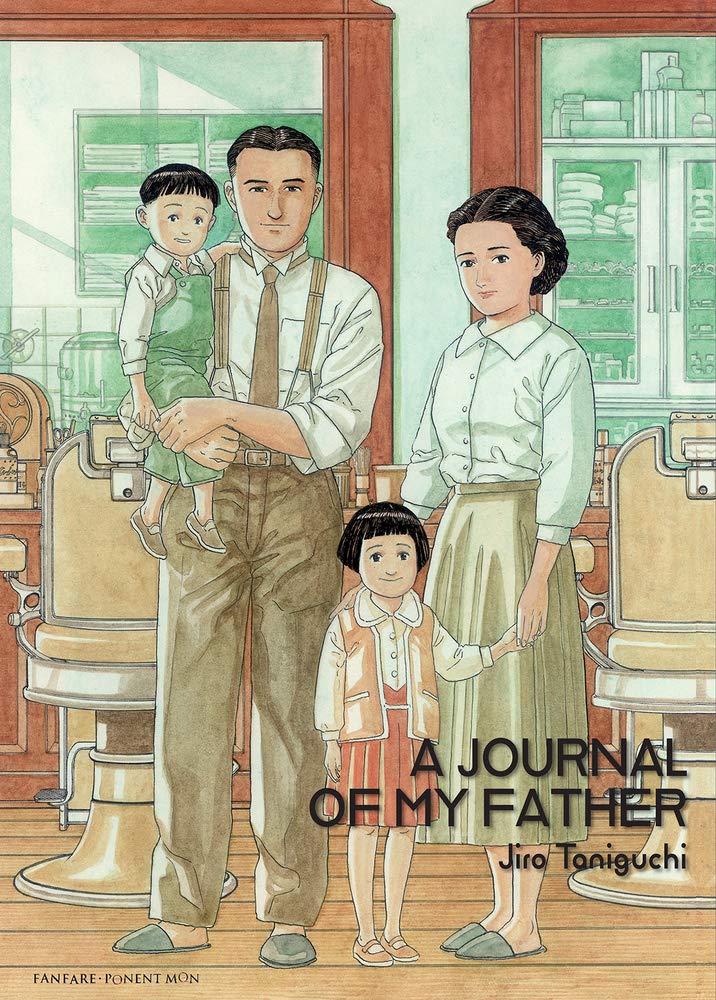

The first person narrative combined with the title A Journal of My Father suggests this is biography, when in fact Jiro Taniguchi is constructing fiction, although feeding in elements of his own 1950s childhood in the northern Japanese city of Tottori. How much is fiction and how much is autobiographical is left open to speculation, but that speculation is further generated by subsequent work A Distant Neighbourhood also being wistful recollections of a past concerning a father never completely understood. That was pieced together from childhood memories and offering the opportunity to change that past, while childhood memories here are contextualised by what was unknown to the narrator of A Journal of My Father.

An insight into Japanese culture extending past the end of World War II is given when it’s pointed out how strange it is that Take Yoshimita and his wife Kiyoko married from love rather than a convenient arrangement. The latter occurs subsequently when Take marries for a second time. The viewpoint is that of Take and Kiyoko’s son Yoichi, who returns to Tottori for his father’s funeral, having not been home for fifteen years.

As Yoichi talks with other family members they add their knowledge to his memories, and the rather distant barber of his childhood and teen years comes to be seen in a different light. Crucially, Taniguchi doesn’t present a misunderstood saint, but a complex man with a strict sense of right and wrong, which is what eventually drives a wedge through his marriage.

The delicacy of Taniguchi’s linework is a wonder to behold, and time and time again attention is caught by the stunning way those lines combine for an everyday scene that’s beautifully rendered. This isn’t just a case of the plot being illustrated as the illustrations are crucial in showing the simmering suppressed emotions providing the story’s core. There are no shortcuts to Taniguchi’s art. He doesn’t build toward one eye-catching image on a page, or use continual close-ups, but provides a fully detailed illustration for every panel. The astounding effort put into a spread showing Tottori after a natural disaster is more work than poor artists put into an entire graphic novel.

Because he’s not been home for so many years, and the period before departure was focussed on leaving, there are ways in which Yoichi is emotionally stuck in the same place. The recollections and revelations are gently, but precisely told, forming an emotional deluge eventually generating regret. It’s quiet and sometimes distanced, but hits home with a powerful punch to make readers consider their own family relationships.

In 2001 the French translation won the Angoulême festival’s Jury Prize, awarded to a single work each year not originally created in French.